Some of Tribeca Film Festival’s lesser-known documentaries and fiction films were the strongest I’d seen in the program. There were certainly standouts, films that had what seemed like impossible footage of an event—Alias Ruby Blade shares secrets firsthand from within the heart of a country’s rebellion—or feature films that explore familiar territory with nuance and care. Many of these films will be worth tracking down if they find distribution.

Alias Ruby Blade is the international handle for Kristy Sword. The Australian had an interest in East Timor in the early 1990s, a time when the nation was boiling under Indonesian governance. (Indonesia had invaded East Timor in 1975, and annexed the country the following year.) Director Alex Meillier reconstructs Sword’s youthful Super-8mm footage into a story of romance and revolution, from when she first moves to East Timor and begins to work for the resistance, assumes her codename, and gets so close to the revolution’s inner world that eventually she becomes the only contact that charismatic leader Xanana Gusmão has outside prison. Before being arrested for treason, Gusmão had become a beloved national figure, leading the revolutionary forces for independence while in hiding.

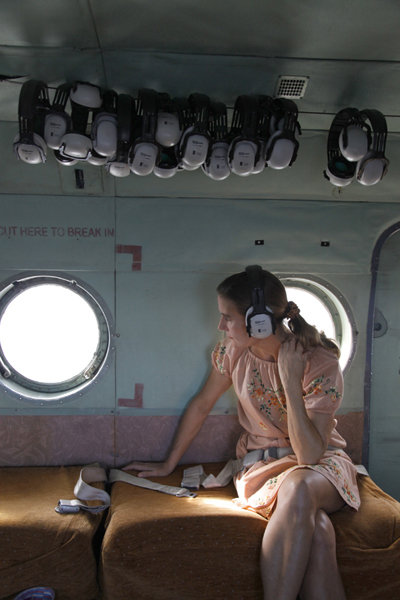

Sword becomes Gusmão’s connection to the outside world, delivering messages to rebel groups and pleas to world leaders. At one point, Sword sneaks a movie camera and a cell phone into his tiny detention center for political prisoners. This is a documentary with the rare advantage of having caught the unfathomable on film, and uses it well. The footage of the two of them talking to each other, exchanging cassette tapes, phone calls, and small gifts, comes into focus as an impossible romance between a young freedom fighter from Melbourne and a warrior-poet, who inspired a nation to revolt. Then the revolution begins, which we see also from home movies: the struggle for East Timor from a first-person perspective with access to the heart of the revolution.

Does Sword survive? Does Gusmão? Can they stay together? Can their country? Don’t let Wikipedia spoil the plot for you. Candid interviews with Sword and major players in the politics of the country known today as Timor-Leste round out an unbelievable story of two people coming together and fighting for their beliefs.

Where Alias Ruby Blade was made from raw material that was innately compelling, Bending Steel was less fortunate. The topic has promise: Chris Schoeck, an awkward and shy subject, has nevertheless spent years training to become an old-timey carnival strongman. He challenges himself daily to bend ever-thicker pieces of steel, performing tricks of superhuman strength—pulling apart phone books and decks of playing cards. He sets a goal for himself: to perform on stage and bend a two-inch bar of steel. Both goals seem large to him, but they aren’t very cinematic. Schoeck is someone with complicated emotional boundaries that would need to be explored in order for his very internal goals to work as a climactic structure. But director Dave Carroll doesn’t go far enough in interviews with his subject or the few people who surround him. There is rarely enough insight to make Schoeck’s trajectory resonant.

Powerless is another documentary that took a shot in the dark, somewhat literally, by tracking a year in the life of its subjects and hoped for the best. A former British factory town in ruins, Kampur is still known in memory as India’s Manchester, though the city’s factories are now shuttered and the homes are dark at night. The state-run electricity company cannot support the amount of power needed by Kampur’s population. In a city of three million, an estimated 400,000 people live without power. Most have resorted to stealing electricity, resulting in a capitalist catch-22: how to improve an electricity company with no money, and how to make an impoverished population pay for something that they’re now accustomed to getting for free?

Directors Fahad Mustafa and Deepti Kakkar track two controversial figures in this north Indian city’s quest for electricity. An expert electrical thief, Loha Singh, helps poor families steal power each night, and Ritu Maheshwari, the power company’s first female managing director, hopes to affect dramatic change. They are two sides of the same idealistic battle, and neither wins. Powerless seems to point to bureaucratic failure to understand how the electricity company’s failure began, which is needed to understand how to fix the problem. It can be fascinating to watch Maheshwari fail in interactions with her customers and employees, or Singh get into disputes with other Kampur residents who criticize his chosen profession. But this is a film that needs talking heads. The film presents the size of the energy problem in India but never quite articulates the background behind the situation, or points to a pathway towards improvement.

Aatsinki: The Story of Arctic Cowboys is a documentary in the truest sense of the word. Filmmaker Jessica Oreck documents a year in the life of two reindeer herders in Finnish Lapland within the Arctic Circle. Without narration or even narrative, we watch two brothers, Aarne and Lasse Aatsinki, at work and at home. There are no interviews or voice-overs to shed more light on these men than what we are shown. That helps create a beautiful portrait, if lulling. The landscape is gorgeous—ice-covered trees, snow deeper than most people have ever experienced, and a look into an ancient and rugged lifestyle that is modernized but still inextricably connected to the land and the elements.

It’s at times an entrancing portrait, a way of life preserved on film, but that sense of magic wears off without a narrative. There are only so many shots of men silently creating a campfire (and there are more than five of those here) or once again flaying a deer that remain interesting without more direct engagement with the men.

Among the feature films, Irish filmmaker Lenny Abrahamson’s excellent What Richard Did is a nuanced portrayal of teenagers that persists in digging below the surface. We are first introduced to a high school rugby team, all boisterous and ready to party, all equally dangerous in their own way. Richard (Jack Reynor) emerges as the group’s alpha male, outgoing though clearly holding back an inner life that he shies away from sharing.

Richard is comfortable with his family and friends as a leader, showing good-natured adult humor and a diplomatic morality. He’s even happy in his role as the group’s aloof sexual fantasy for the girls of the group until Lara (Roisin Murphy) enters his life. She leaves her boyfriend for Richard, creating tension between the three that pulls him into an act of uncharacteristic violence, which the film’s ominous energy has promised from the start. But the pleasure in watching this film comes not from the plot arc but from being introduced to a solidly drawn character, and watching him respond with subtlety to a situation forcing mature growth, and it works because Reynor carries his role well.

Director Tomasz Wasilewski has made what has been called Poland’s first gay film, Floating Skyscrapers, a sophomore film tense with anticipation. A 20-something swimmer-in-training, Kuba (Mateusz Banasiuk), becomes restless in his comfortable relationship with his girlfriend once he allows himself to feel a romantic interest in Mikal (Bartosz Gelner). Their attraction and connection is powerful enough for both of them to completely come out of the closet.

However, they live in a society that threatens homosexuals, bruising the bold, leaving only muffled thumps in a locker room as a safe expression of desire. In Poland, LGBT rights and views on homosexuality are stuck behind much of Europe. The film’s beautifully shot, and Warsaw becomes both romantic and alienating in Wasilewski’s framing. In his lens, the city is full of promise for people in love and those lucky enough to be able to take advantage of it, and claustrophobic for those who can’t.

Leave A Comment