If success is all about promotion, then the fact that this is the debut directing effort by comic actor Mike Myers is one part of the package. Amidst the constant name-dropping, testimonials, and testosterone-fueled preening in Supermensch: The Legend of Shep Gordon, there are, fortunately, some good examples of how Gordon succeeded for more than 40 years as a manager in music, the movies, and any other part of the entertainment business that hit his fancy, representing friends who, luckily, were talented.

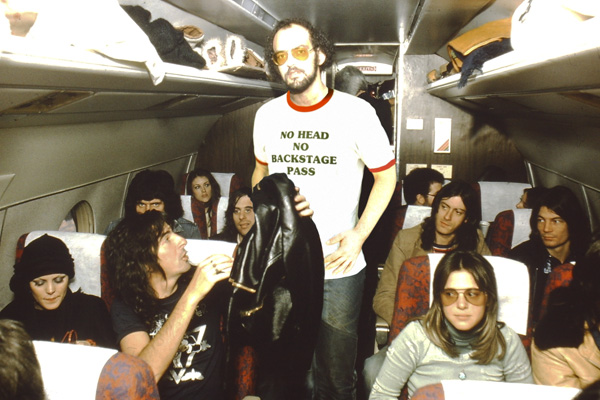

After leaving his unhappy Long Island home in 1968, he happened to stay at the same partying motel in Los Angeles with Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. Gordon agreed to be their manager in a briefly sober moment. He parlayed these connections into a full-time, full-service business of managing sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll on the road and in the studio.

Amidst endless braggadocio and nostalgic belly laughs (with some self-deprecating ethnic jokes thrown in), he admirably insists on his financial honesty and reliability for his clients in an industry notorious for neither: “Get the money. Always remember to get the money. Never forget to always remember to get the money.” His brief management and promotional tips are fun and insightful, including how he sold out Alice Cooper’s first performance in London by staging a mobile billboard breakdown in Piccadilly Circus (among several Gordon tricks Alice Cooper chuckles over) and made pop singer Anne Murray seem hip and cool by getting rock stars’ endorsements.

Gordon is just as quick to not-too-modestly note when his assistance was pro bono, such as his work for the elderly, financially strapped Groucho Marx and African-American R & B artists, who, he claims, were still trapped promoting their records in the low-yield chitlin’ circuit in the 1970s. His involvement as a producer/distributor for more than 40 independent features, from Ridley Scott’s The Duellist (1977) to Lindsay Anderson’s The Whales of August (1987), goes by in a quick montage of movie posters and award mentions, while several women who have worked for him as assistants in this and other of his ventures are full of praise.

It’s possible that Myers, as his friend for over two decades since a tough negotiation for the use of an Alice Cooper song in Wayne’s World (1992), doesn’t see the irony of someone living in luxury in Maui and professing deeply to being a “JewBu” (Jewish Buddhist) and a devout follower of the Dalai Lama. (The Dalai Lama’s representative is certainly grateful for the large contributions to his Tibet Fund.)

Gallingly, Gordon claims he warned his client Teddy Pendergrass of inevitable karmic payback from his concert cancellation shenanigans shortly before Pendergrass’s debilitating car accident. Yet his frequent plaint of childlessness rings no karmic bells for him as he describes his stream of backstage hook-ups and proud affairs with a string of beautiful women (including Sharon Stone). His taking on financial responsibility for an African-American ex-lover’s orphan children is touching, even if the degree of his involvement doesn’t seem much deeper than his pocket and occasionally hosting them for a Maui vacation.

The strung-together anecdotes and funny stories by Gordon and his famous friends and clients (Michael Douglas talks a lot) recall Robert Evans holding court in Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgen’s The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002), but without the creative animation or the visual dazzle of the overlapping bio-doc Super Duper Alice Cooper, shown at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival. It is impossible not to be sympathetic, though, as the 68-year-old Gordon is seen struggling through a recent life-threatening illness, so it may be timely that Myers filmed his stories so that he can now bask in this fond tribute.

Leave A Comment