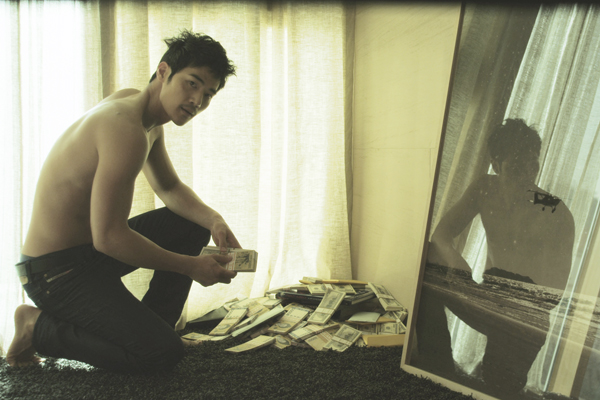

Kim Kang-woo in THE TASTE OF MONEY (Sundance Selects)

In an early scene in Im Sang-soo’s lurid, arty soap opera The Taste of Money, we are directly informed of his film’s overriding message, which will be repeated many times before its conclusion. Young-jak (Kim Kang-woo), salaryman/errand boy for one of Korea’s wealthiest and most powerful families, is taken by his nominal boss, Yoon (Baek Yoon-sik), into a vast, cavernous vault stacked with bundled cash from floor to ceiling. Some of this money will be used to bribe officials into letting Yoon’s son off the hook for corrupt business practices, and after they collect enough cash for the bribe, Yoon tells Young-jak, “Take some for yourself. Everyone does it. Have a taste.” Young-jak happily obliges.

And there you have it. Im’s film is based on the hardly revelatory notion that vast wealth and power barely hides deep corruption, an idea brought home here with lots of scenes of salacious sexual activity. The Taste of Money is an extension of, and a very loose sequel of sorts to, Im’s previous film, The Housemaid, his remake of Kim Ki-young’s 1960 Korean classic. While The Housemaid, with all its class-based anger and kinky sexual exploits, ultimately pales in comparison to its source material, The Taste of Money is able to go much further in its critiques of upper-class decadence, freed from the shackles of reinterpretation (although Im directly quotes from both versions of The Housemaid).

While spending two hours in the company of mostly venal, vindictive, and ruthless characters is not all that dramatically satisfying, much fascination and amusement can be had in the spectacle Im creates and the obvious schadenfreude he seems to derive in showing us this powerful family sinking under the weight of its own corruption. Although Young-jak initially seems to be the most sympathetic character, torn between his own ambitions and his growing disgust with his employers’ increasingly cruel actions, his struggle is eventually shunted aside. Most of the film focuses on the power struggle between Yoon and his wife, Keum-ok (Youn Yuh-jung), who emerges as the true villain of the piece.

Yoon laments his depression over being trapped in a loveless marriage, which he tries to assuage through many extramarital affairs. Much like Im’s previous film, there is a relationship between an employer and a housemaid. This time, that domestic servant is Eva (Maui Taylor), a Filipina with whom Yoon actually falls in love with. After the wife discovers the affair through the surveillance camera she has installed in Yoon’s room, he declares his wish to leave the family and live with Eva. Keum-ok cannot let this stand, and sets out to completely destroy both of them. Along the way, as a sort of revenge, she seduces Young-jak in a scene mostly played as a grotesque spectacle as it accentuates the age difference between the two.

There are various other subplots reinforcing the theme of corruptive wealth, for example, a shady deal involving an American businessman (film critic Darcy Paquet), and a rather underdeveloped romance between Young-jak and Nami (Kim Hyo-jin), Yoon and Keum-ok’s daughter. But Im is far less interested in well-rounded characters or even dramatically compelling plotting than he is in exposing what he feels to be his country’s dangerous obsession with amassing more and more material wealth to the detriment of any sort of human values. His characters roam a vast mansion with dark, looming shadows resembling a mausoleum, leading to a concluding image of money lying next to a corpse in a coffin, making very clear his assessment of where the pursuit of money and power ultimately ends.

Leave A Comment