The current demonization of Wall Street may have helped trigger the current protest movement, but there’s an even more hated entity in the minds of most Americans: Big Tobacco. Cigarette companies are the most egregious example of corporate greed and heartlessness that predates what’s now on the daily news and in the streets. Its success is perpetuated by shrewd marketing that has kept millions of Americans smoking (and dying) from the teen years on (and sometimes even earlier).

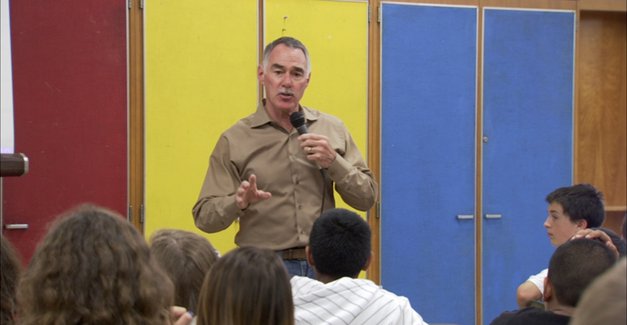

Charles Evans Jr.’s documentary Addiction Incorporated shines a flashlight on

the underhanded tactics that rope smokers in. It’s not simply a shrill polemic as Evans allows tobacco company defenders to have their say. Since that say is often spin 101, it doesn’t take much to show how absurd and unethical their position is. (There’s a delicious moment when all seven Big Tobacco CEOs affirm, under oath at a congressional hearing, that they believe that nicotine is not addictive.)

Victor DeNoble, the movie’s protagonist, worked for a tobacco company in the 1980s as a research scientist. He helped create a new form of nicotine in the lab that was less lethal but more addictive, so smokers would be stricken by fewer diseases, and, it was assumed, continue their habit for years to come. But when his research also showed that nicotine was an addictive drug—much like heroin or cocaine—that was too much for the powers that be. Right before the studies were to be published in a journal, DeNoble found out that his lab and all of the research was to be shut down and that he and his fellow scientists were going to be fired. When Congress and the Clinton White House geared up for a round of hearings and meetings to determine the severity of cigarettes, it fell to DeNoble—despite a confidentiality agreement he signed—to expose the tactics of Big Tobacco as a cynical attempt to cash in on its customers’ addictions.

Evans’ journalistic exposé is similar to recent documentaries in its reliance on solid reporting and a myriad of talking heads to chronicle malfeasance on a grand scale, like in the Oscar-winning Inside Job, about the Wall Street scandals that brought the world’s economy to its knees. Much of the information laid out here is not new, but Evans binds it together in a tight, taut package that brings many opportunities for viewers to shake their heads in disbelief of how profit-first corporations treat, or mistreat, consumers.

The terse accumulation of evidence includes eye-openers, like how billion-dollar companies take care of their own. ABC blinked after tobacco giant Philip Morris filed a multibillion dollar lawsuit against the television network for a 1995 Nightline expose. Diane Sawyer apologized on air for what was essentially a difference of opinion.

There are missteps. It seems that Evans thought that 100 minutes of talking heads and footage of congressional hearings would become repetitious and redundant, and so he succumbs to the current “reenactment mania.” In the hands of Errol Morris, whose The Thin Blue Line became unbearably tense due to his detached reenactments of events surrounding a police officer’s murder, it’s one way to display nuances that interviews can’t. But in other cases (all History Channel specials and here), reenactments simply get in the way. This isn’t the Watergate break-in being discussing, it’s the laying out of a mountain of evidence. Showing researchers in the lab doesn‘t bring anything of substance to Evans’ truth-telling. Similarly, lighthearted use of animated rats (subjects of DeNoble’s nicotine testing) blissfully reacting to the drug is cute but unnecessary.

While people may be understandably cynical over the marriage of government and big business—indeed, a federal judge recently blocked new FDA warnings on cigarette packages as something that would inhibit tobacco companies’ free speech—Addiction Incorporated can be seen as both a corrective and cautionary tale about the fallout when big business calls its own shots, even in what should be an ethically neutral area as scientific discovery.