Soprano Natalie Dessay and stage director Jean-François Sivadier (The Film Society of Lincoln Society)

With two extra screens at its disposal, the New York Film Festival has added more sidebars to its programming, which means additional events have been packed into its 17 days. It was once possible to see a generous slice of what the festival had to offer. Now its an uphill battle just to see many in the Cineaste/Cinema of Our Time section. The array of choices will cause vertigo for any film buff, mostly European-produced documentaries on John Cassavetes, George Cukor, Erich von Stroheim, Jean Vigo, Hou Hsiao-hsien, to name a few. The annual Masterworks shows off the digitally restored Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Lawrence of Arabia, and quite an eclectic mixfrom Fellini Satyricon to Frank Ozs Little Shop of Horrors. And following the footsteps of Toronto and Tribeca festivals, NYFF has its own midnight movies showcase for genre films that have traditionally been underserved, if not outright ignored, in the past (see below).

If the following two films are any indication, the sidebars enhance and complement the overall selections. In the “On the Arts” sidebar, Becoming Traviata plants the viewer in a rehearsal room and lets the camera roll as stage director Jean-François Sivadier and his star, soprano Natalie Dessay, break down Verdis score and Francesco Maria Piaves libretto to find clues to the consumptive courtesan Violetta in the 1853 warhorse opera La Traviata. Sivadier focuses on the Violettas motivation to leave her Parisian high life and allow herself, for the first time, to fall in love. The stage director refrains from imposing a conceit or conceptthis is the opposite of regietheater. In contrast, the Willy Decker production at the Met features an omnipresent clock ticking away on stage, a constant reminder that Violettas days are numbered. The current version at La Fenice plays up the decadence, a la Americana, with stripping cheerleaders and cowboys.

Dessay is the undisputed star of this 2011 production from Aix-en-Provence Festival in Franceand Philippe Béziats documentary. Shes one of the best actors/singers out there, and she takes Sivadiers insightful direction and runs with it. You might argue about her voice being too light for it, but you cant disregard her commitment to the role; the old-school park-and-bark acting style is not in her arsenal. This documentarys about the demands of acting as much as it is about opera. Maybe more so. And the film ventures far beyond the typical making-of backstage look. The thorough, detail oriented discussions will appeal to those who listen to DVD commentaries for directorial secrets. Here you wont have to wait so long, and the generous excerpts of the score will seduce you, if it hasnt already.

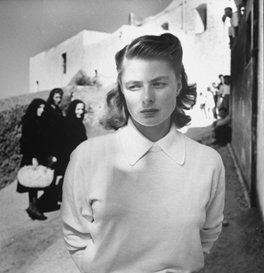

Ingrid Berman on location, Stromboli island (Gordon Parks/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

In the new section about movies and filmmakers, Cinema Reflected, The War of the Volcanoes relives the international scandal of 1950: world famous director Roberto Rossellini dumps his companion and frequent leading lady, Anna Magnani, for married Hollywood star Ingrid Bergman, who becomes pregnant with his child. Meanwhile, the two actresses embark on competing film productions, each with competing directors named for their respective locations: Stromboli, Terra di Dio and Vulcano. Both are about outsiders isolated and ostracized on volcanic islands, each with the requisite climactic eruption. Rossellini was originally going to direct Magnani in Vulcano, and then went in another direction, casting Bergman in Stromboli.

By far this docs greatest asset, the archival footage brings a high-toned tabloid story to life, especially the clips contrasting the fiery Magnani and the cool Nordic Bergman. The narration, though, simplifies the playersMagnani is reliable and faithful, Rossellini mercurialand breathlessly informs us that during the protracted Stromboli shoot, Bergman abandons herself to Roberto. (The film demurs to mention that Rossellini was already married to a third woman while all of this drama exploded.) Both films flopped upon their release, and the scandal probably irreparably hurt Rossellinis film. News of Bergmans affair completely capsized her public image; she had played Joan of Arc, after all, not to mention she had a husband and a young daughter waiting for her in the States. Unlike the hullabaloo involving, say, Elizabeth Taylor, which enhanced and confirmed Taylors brazen public image, this scandal was a jarring contrast to Bergmans Hollywood career. Unfortunately, viewers cant see the film, Rossellinis first departure away from his earlier neorealism work, to judge for themselves. The NYFF, strangely, will not be screening the newly restored version of Stromboli, which was unveiled only last month in Venice. Kent Turner

More from the Sidebars:

Ingmar Bergman and Liv Ullmann

The title of Liv and Ingmar says it all: two names forever linked in the annals of 20th century film history, muse/Norwegian actress Ullmann and Swedish director Bergman. The alchemy of their long, legendary collaboration (12 films over 42 years) began when she was 25 and he was 47. Both were married to others. Indian director Dheeraj Akolkar deftly edits together resonant movie clips, stills, behind-the-scenes footage, and readings from Ullmanns and Bergmans autobiographies. The new elements include Bergmans love letters and interviews with Ullmann, poignant but self-consciously theatrical, as she moves around the house he built for her on Faro Island, an isolated locale where he first declared his love and gradually, over five years, made her feel imprisoned with their daughter. In this art-house equivalent of a visit to Oprahs couch, Ullmann talks a lot about how love, Sturm und Drang, maturity, and her independent career choices led her to reconcile with Bergman as a friend and, even more so, as a soul mate. The film will be even more titillating for fans delving into their masterpieces when the pairing was off-screen tabloid fodder.

Celluloid Man fondly traces the history of Indian cinema through the obsessive activities of P. K. Nair, film lover and archivist extraordinaire. Director Shivendra Singh Dungarpur helps the 79-year-old Nair track his passion for movies from a childhood of sneaking out at night to his neighborhood movie theater (and notating every film he saw) to his founding of and collecting for the National Film Archive of India. Visits to now-ruined silent film studios point out how timely his arduous efforts were in saving even nine of the countrys 1,700 silent movies. But among dozens of beautiful film clips, the warm (and unfortunately repetitive) memories of many Indian actors and filmmakers cite the tremendous impact he had on the students of the adjacent Film and Television Institute. While Nair minutely recorded the condition of each reel (and memorized each scene), he let students sit in on screenings of new arrivals from around the world that he begged, borrowed (and stole) from other archives. Despite the on-screen tributes, there is not, surprisingly, a happy or uplifting ending. Its a visceral shock to see the mechanical process of silver being profitably removed from silver nitrate film stock, and a tragedy that corroding canisters have been neglected since a 2000 fire in the archive after his unwilling retirementobsessives have a way of ticking off administrators (not interviewed), let alone the family he hardly saw. But his zeal reached rural villagers, who enthuse about his traveling series that brought the most challenging of world cinema to the far hinterland. Thanks to Nair, Indias movie fans have a love that expands beyond Bollywood, though no one seems, shockingly, to be saving the countrys homegrown film output any more.

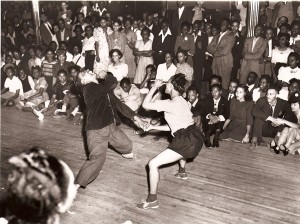

A scene from the Savoy Ballroom

With its new On the Arts sidebar, the festival is expanding its documentary offerings to reflect its home at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. The Savoy King: Chick Webb and the Music That Changed America lovingly pieces together images, sounds, and memories to compose a fascinating biography of the African-American swing era drummer. His meteoric career was as brief (he died in his early thirties) as it was influential, including his mentoring teenage Ella Fitzgerald to stardom. Even aficionados may not know that he first took up drumming as physical therapy in segregated Baltimore to cope with injuries and illnesses that left him a stunted hunchback. Interviews with family, musicians, spry nonagenarian club denizens and dancers are interspersed with notable voice-overs conversationally quoting his colleagues, including Janet Jackson as Ella, Danny Glover as Count Basie, and Jeff Goldblum as Artie Shaw. Through archival photographs and rare film snippets, director Jeff Kaufman explores the cultural history of the 1930s, when African-Americans musicians were beginning to have crossover success. (Webb was the house bandleader for Harlems first integrated night club, the Savoy Ballroom, and the first black host of a national radio show.) A historical irony is vividly demonstrated in the exciting 1937 Battle of the Bands between Webb and Benny Goodman at the Savoy, where Goodmans turn was fully documented on filmand Webbs win can only be recalled through a few photos and the enthusiastic memories of those who crowded into his club. This film joyously revives that legendary night.

Punk in Africa follows the recent Searching for Sugar Man in introducing international audiences to the alternative music young South African whites were rocking out to when apartheid kept the country isolated and divided. At the time, the wider world was not much aware that the government troops seen on the TV news battling Nelson Mandela supporters included dissident conscripts in its ranks. Under oppressive censorious restrictions, young men facing the draft created an underground music scene. Gray-haired alumni of these bandssuch as Gay Marines, Screaming Fetus, Suck, and Wild Youthrevisit the ruins of their downtown hangouts, and try to convey their significance to young black kids following the cameras. Loud song clips surround interviews, accompanied by a dizzying montage of photos, posters, album covers, and some grainy performance video. The most controversial bands sang in Afrikaans, and discussions of diversity within Afrikaners culture add a fresh perspective. Directors Keith Jones and Deon Maas expand beyond music to graphic art zines and photography to insightfully broaden the cultural context. However, they stretch the segue a bit too far in labeling ska and reggae fusion bands challenging their countries recent political problems in Mozambique and Zimbabwe as afro-punk.

The Rolling Stones-Charlie is My Darling-Ireland 1965, world premiering in the Masterworks series, is an exquisite rock n roll time capsule of the band (who are also celebrating their 50th anniversary) when they were just exploding from a popular rootsy and R & B cover band to superstardom. This painstaking restoration by director Mick Gochanour and producer Robin Klein of the rediscovered concert and backstage footage is styled and paced like a cross between the verité of DA Pennebakers Dont Look Back of Bob Dylans U.K. tour that same year and Richard Lesters madcap A Hard Days Night of the Beatles in 1964. (The Stones also break into folk tunes and a Beatles song.) When the audience rushes onstage at one performance, it foreshadows the lack of restraint the Stones later unleashed in the Maysles Gimme Shelter (1970). As marvelous as it is to watch Mick Jagger developing his front man persona thats here barely more than an imitation of James Brown, it is more sentimental if you have worn out their early LPs to see the late Brian Jones ponder his future, a fresh-faced (!) Keith Richards experiment with now familiar riffs on the guitar, and staid bassist Bill Wyman and drummer Charlie Watts grinyes, grin. The never-released original 1965 cut and this dazzling expanded version will be available together in a DVD box set on November 6th before its television broadcast.

World premiering in the “Arts” section, Deceptive Practice: The Mysteries and Mentors of Ricky Jay is much more than a biography of the entertainer/magician par excellence and serious scholar/promoter of the sleight of hand. Directors Molly Bernstein and Alan Edelstein delve into how he fell in love with and persistently perfected this ephemeral art. The charming heart of his inspiration is his close relationship with his grandfather Max Katz, an amateur magician who supported his family in Brooklyn as an accountant to the pros. These friends welcomed little Ricky into their fraternity when he was practically a toddler and encouraged his performing career, starting at age of seven. Jay recounts how he earned the trust (after hours and hours of practice) of each master, who agreed to let him apprentice (always saving some mystery unrevealed). Though Jay shuts down discussion of his later family estrangement, his reminiscing, supplemented with rare archival footage, photographs, and paraphernalia from his collection, warmly brings to life those known now only to cognoscenti. (In New York, names like Slydini and Cardini evoke a quaint, vaudevillian past.) The films key lessonthe importance of passing (some) secrets on to a new generationstays tantalizing in sight. Nora Lee Mandel

A scene from THE BAY

Midnight Movies

For those who can stay up until midnight, Berberian Sound Studio stars Toby Jones as Gilderoy, a nebbishy but in-demand movie sound designer summoned to work on an Italian giallo film. Taking place entirely inside the chiaroscuro of a recording studio, Gilderoy is never at ease. Whether hes being taken advantage of by the stereotypically greasy Italian producer regarding his paycheck and expenses, or finding himself surrounded by a web of nebulous sexual intrigues, Gilderoy watches his back ceaselessly. His relative innocence is a major contrast to the rest of the subversive cast of characters as writer/director Peter Strickland fashions this paean to one of the most influential horror subgenres ever to bombard the screen. Watch for a sometimes unsettling, sometimes hilarious rivalry between Gilderoy and the curmudgeonly sound engineerif nothing else a fine example of the richness that this celebrated cult genre can offer.

Also showing is Barry Levinsons truly horrifying The Bay, an interesting offering from the director of Rain Man and Diner. Its composed of various types of footage found years after a deadly outbreak of waterborne parasites hit a small Chesapeake Bay community. Through home video, news coverage, security camera backlogs, and even a COPS-style police cruiser fisheye lens, we watch in shock as tiny, mostly unseen parasitic invertebrates terrorize the town.

Beautifully shot in a plethora of camera formats, the film has something that perhaps others of its ilk (see Paranormal Activity, or rather, dont) lack: a seasoned director of actors. From a cast of mostly unknowns, an engaging story appears out of what was reportedly a long and complicated edit. Thanks to Levinsons keen understanding of the medium, even in this complex and disjointed form were never confused about where we are in the films world. The shock moments hit home extremely well (they are terrifying, and you will jump in your seat), but the most impressive aspect is the heightened level of storytelling. Cineastes without a taste for copious blood and guts, though, might want to think twice before biting into this one. Michael Lee

Last updated October 15, 2012

Leave A Comment