As with most streaming platforms, there is a seemingly endless supply of documentaries on Netflix to sift through. At its worst, this abundance is so overwhelming that it’s impossible to decide which one to watch. At its best, it testifies to the curiosity and perspicacity of many filmmakers. These three documentaries are united in their intentions. Each, in different ways, is determined to celebrate and stand up for people with the odds stacked against them, though they do so with varying degrees of success.

Mountain Queen: The Summits of Lhakpa Sherpa opens with Lhakpa Sherpa returning to her native Nepal to scale Mount Everest. It is clear that she has accomplished this feat before, and she states that she is again doing it, in part, to model courage for her daughters. The wind blows violently, the music is appropriately grandiose, and her crew keeps watch over her oxygen tanks. One daughter waits at base camp, communicating with her mother via walkie-talkie. (The other daughter is back home in Connecticut.) All are poised to witness Lhakpa complete her monumental task.

Yet, the film does not rigidly follow this most recent journey up the mountain but instead fills us in on her life leading up to it. This is not merely the second time Lhakpa has summited the world’s tallest mountain: She holds the world record for the most ascents by a woman. She is also the first woman ever to scale Everest. Still, at the time the profile begins, she has been working at a Whole Foods, and many of her coworkers have no idea of her illustrious past.

You could argue that Mountain Queen’s scope is as vast as the mountain at its center. It uses a combination of interviews, footage from previous mountain trips, and coverage of her current journey to address a wide variety of subjects. There’s Lhakpa’s childhood in a culture where women were not allowed to climb mountains; the father of her first child who abandoned her; and her relationship with her husband, a Romanian emigrant who became violent and abusive toward her.

Throughout, Lhakpa mentions that her decision to summit one last time is to help herself and her family heal by proving that she can still achieve in the face of hardship. The film seeks to celebrate her resilient spirit, and many sequences are impressively captured in dangerous conditions at high altitudes. While it is easy to admire Lhakpa, the filmmakers somehow fail to illuminate her fundamental uniqueness. The result is as bland as the average Hollywood documentary. The homogenous tone makes it feel like a sports movie at times and a sentimental melodrama at others. Director Lucy Walker (Waste Land) insists upon the inspirational message but does so without exploring the psychology of mountaineering, which drives many to their deaths.

Daughters, a much more assured documentary, is also one of great scope. It takes as its subject a program called Date with Dad, which allows incarcerated fathers to meet with their daughters in person for a dance, provided they go through a coaching process with a mentor. Many of the girls have not seen their fathers in years; many of the fathers have been in and out of prison multiple times. The timeline follows the lead-up to and the aftermath of the dance. All the families are Black, and systemic racism is implied more than actively discussed.

Though there are some slightly expressionistic sequences of the girls at play, most scenes depict the families together and apart, interviews with the subjects, and the dance itself. Through the testimonies of the girls of different ages, the viewer gains insight into the varieties of emotional experiences within their circumstances. The older girls are more likely to feel a mixture of resentment and longing (Santana, age 10, says she will never be a mother), while the younger ones are more dominated by confusion.

The film is at its best in the mode of clear-eyed observation, not straining for emotional effect, though it sometimes does. The dance sequence, while employing some heart-tugging music, is beautifully observed, capturing the variety of relationships at play and the incredible impact this reunion has on both parties. Aubrey, age five at the beginning of the film, insists on saying “see you later” rather than “goodbye” when it is time to leave.

Angela Patton and Natalie Rae’s film hammers home its well-earned and important message: Compassion is a greater tool for rehabilitation than anything else our punitive incarceration system offers. We see it in effect when some fathers return home and slowly work to earn their families’ trust back. The startling yet heartening statistic that 95 percent of the program’s participants have never returned to prison since its founding 12 years ago is revealed at the end. Yet, some fathers do not return home and even have their sentences extended by decades. Daughters is a strong and ambitious film that treats its subjects with dignity.

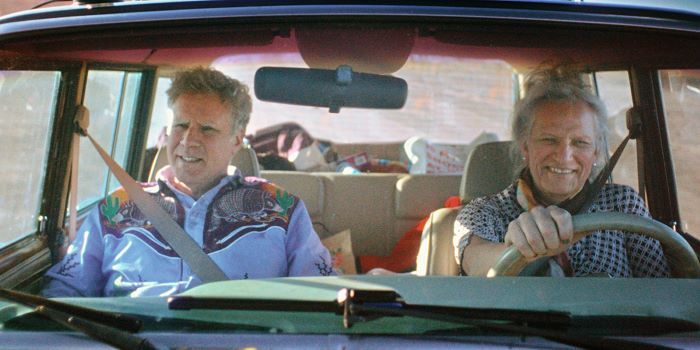

Director Josh Greenbaum’s Will & Harper brings us into the realm of celebrity. During the pandemic, Will Ferrell received a call from his longtime friend, writer Andrew Steele, who informed him of surprising news: Andrew was coming out as a trans woman, Harper. Though Ferrell was initially shocked, his response was compassionate. As Harper discussed her desire and fear of entering places she used to love as a cisgender man, Ferrell proposed a road trip together, so Harper could revisit these places with his support. Their journey became this documentary.

Between the cross-country stops, Will asks pertinent questions, sometimes with an eye toward humor (“How do you like your boobs?”), and Harper shares the incredible pain she’s endured for years (uncompassionate therapists, repressed emotions) and the central question most trans people face: Will my loved ones accept me as I am? Harper’s implicit second question is: Will these places accept me as well?

There is a degree of safety in Will & Harper that many trans people are not so fortunate to have—Harper is accompanied by a celebrity and a film crew. Ferrell’s compassionate gestures toward Harper are sometimes moving, and it is heartening to encounter some outwardly accepting strangers in unlikely places. However, hateful attitudes also make themselves known, such as when their visit to a Texas restaurant, where Ferrell (dressed as Sherlock Holmes) stands on a table and makes a toast to Harper’s coming out, is met with hate speech on social media. Still, much of this feels controlled.

What limits the film is its lack of intimacy. The conversations feel stilted and staged, even when they include tears. Interestingly, humor almost always feels forced. By the end, while it is easy to accept the duo’s closeness as friends, it is hard to truly feel it. As such, Will & Harper is a vehicle that falls short of its good intentions.

Leave A Comment