![]() Todd Haynes has directed two rock and roll–oriented films: the excellent glam rock homage Velvet Goldmine and the pretentious, to say the least, Bob Dylan hagiography I’m Not There. So, when I heard he was directing a Velvet Underground documentary creatively titled The Velvet Underground, I was trepidatious.

Todd Haynes has directed two rock and roll–oriented films: the excellent glam rock homage Velvet Goldmine and the pretentious, to say the least, Bob Dylan hagiography I’m Not There. So, when I heard he was directing a Velvet Underground documentary creatively titled The Velvet Underground, I was trepidatious.

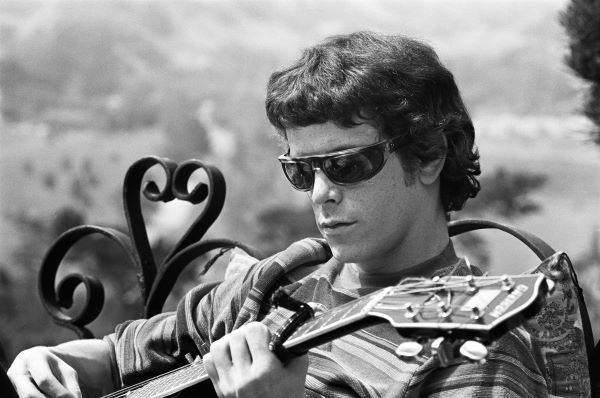

Luckily, it turns out to be a fruitful marriage. The film is a robust and dense two hours, told in chronological order, and it takes roughly 45 minutes before we get to the recording of the group’s first album. Until then, much of it concerns the biographies of Lou Reed and John Cale. Cale is interviewed prodigiously, as is Maureen “Moe” Tucker, the two surviving members of the original lineup. A good chunk of the beginning sets up the culture of the time, the 1950s and early 1960s: the beginning the rock and roll and doo wop that so infatuated Reed and the postwar avant-garde music by the likes of LaMonte Young (also interviewed here) and John Cage that enraptured violist Cale.

Haynes really gives you a sense of place and what New York meant to the young artists who moved there, in part by making the film a full-on aural and visual experience: a combination of wall-to-wall music and rich visuals appearing in split screens alongside the interviews. Haynes’s use of vintage footage is especially impressive. Sometimes it directly expresses what the voice-over or interview is saying, but at other moments, it seems as if Haynes is playing a word association game. The imagery probably matches in Haynes’s mind, but to us, the connotation is loose yet intriguing.

The group disdained the hippy movement. “We hated that peace and love crap,” Tucker snarls, because hippies weren’t realists. These musicians felt they were, particularly Reed, whose trademark brusqueness stemmed from insecurity, according to his sister, Merrill Reed Weiner. Haynes delves into what made the self-taught Reed so unique among other artists. Part of it is standard Velvet Underground lore. Yes, he had electroshock therapy, and yes, he was mentored by the now forgotten poet and short story writer Delmore Schwartz, but that viewpoint gets subtly subverted. For example, Reed’s sister excoriates what has become the accepted story, that his therapy was meant to cure his possibly burgeoning homosexuality and was an example of his father’s controlling ways.

Of course, there is the music, which pretty much helped kickstart punk, glam, new wave, and indie rock. The breadth and range of the band’s music and lyrical content is just breathtaking: Reed wrote a 17- minute song about an orgy (“Sugar Ray”) and then a year later wrote an exquisitely tender song about a drag queen’s gender dysmorphia (“Candy Says”). The first half of the group’s existence consisted of boundary pushing, middle finger showing, and viola shredding music. The second half found them playing essential straight up rock and roll.

This is where Haynes falters a bit. Maybe because Haynes primarily considers himself a more art-house than mainstream filmmaker or maybe because he is more interested in highlighting the scene from which the group came. Andy Warhol and the Factory were prominent in the band’s ascent, but the Velvet Underground was always a separate creative entity. (Warhol designed the cover of their first album, helped promote the band, but did not participate in its production.) In fact, Reed broke from Warhol because he complained that the public though Warhol “was the fucking lead guitarist” of the group.

But the result, the third and fourth albums, the self-titled Velvet Underground and Loaded, get short shrift, as does Doug Yule, the bassist that came in after Cale was fired. In this section, Haynes seems to be looking for the door, which is not too far away as the band broke up soon after. However, the self-titled album is fairly monumental in the sense that Reed, always a pithy observer with a sympathy toward the outcast, really starts going deeper. The need to shock with stories of sadomasochism and drug use wafts away and underneath you find tremendous empathy. This album features two of Reed’s most tremendous ballads, “Candy Says” and “Pale Blue Eyes.” It is a touchstone for many, many indie bands, such as R.E.M. and Belle and Sebastian. The fact that he roars back with a straight up rock and roll album with Loaded, before pulling the plug, seems to suggest that during Reed’s time with the Velvet Underground, he was actually searching for his most free form of expression, which he likely found in his solo career.

Still, this is a thoroughly entertaining and insightful film, even if it’s not the definitive biography of the band. It will certainly be the most distinctive and evocative.

Leave A Comment