“Inferiority. I’ve been close to it all my life.” The voice is unmistakable: sussurant, slurred, sensual, and exhausted. Its meandering cadences emerge from the once beautiful and now bloated Marlon Brando, telling the story of his interior life to a tape recorder. Through recordings, the great actor leads us through a convoluted, tragic tale that alternately absorbs and repels. Beautiful, deeply felt, and claustrophobic, Listen to Me Marlon is a glimpse inside a mind that desperately craved inspiration but too often strayed into cynicism and even nihilism.

Director Stevan Riley has assembled his film from 200 hours the tormented actor recorded of self-hypnosis, acting exercises, confessions, and random musings. This is truly Brando in his own words. The narrative weaves through Brando’s troubled boyhood through stardom, spiritual quests, crusades for social justice, and the tragedies of his twilight years. Stills, film, and press clips from Brando’s storied career, rare home movies, TV news broadcasts, and tasteful reenactments accompany the audio. Sometime in the 1980s, Brando arranged to have his face digitized with early computer technology, and thus we see his pixilated, disembodied head reciting Shakespeare. The head recalls a death mask, which in some ways this movie is. It’s a macabre, surreal touch.

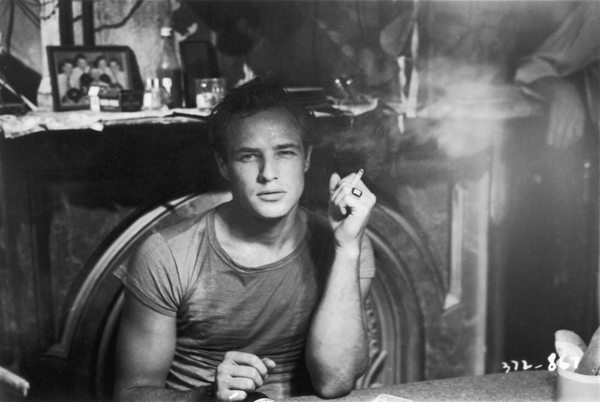

No one in his prime was as irresistibly sexy and charismatic as Brando. He knew it, too, brazenly flirting with women reporters and co-stars in the movie’s few light moments. The young Brando craved sensation and excitement; the older Brando matured into a brilliant actor. Clips from A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, The Last Tango in Paris, and The Godfather show off Brando’s remarkable power and range, and the early beauty and blazing talent make the actor’s later troubles hard to watch. Brando fought with directors, rewrote scripts, pontificated on politics, and indulged himself with bizarre star turns. Toward the movie’s end, Brando’s son Christian has shot his sister’s Cheyenne’s boyfriend, and Cheyenne has hanged herself. Brando looks stunned at the harsh comedown from dizzy heights.

Some of Brando’s struggles were clearly rooted in his ambivalence toward acting. The film bristles with Holden Caulfield-esque indictments of the profession’s phoniness: “There’s no such thing as a good movie. There is no art,” “Lying for a living. That’s what acting does,” and “We all act. Some of us get paid for it.” Giving in to an everything-sucks funk, Brando laments not just acting but the venality and wickedness of the human condition. Luckily the evil apparently skipped his beloved Tahiti: “Tahitians have the beauty of sleeping children, and when they awaken will awaken into the nightmare the white man lives in.”

As the legendary actor bares his soul, it seems uncharitable for a wicked little voice in your head to chime in with a quotation from that ultimate Hollywood insider, Nora Ephron: “Men who cry are sensitive to and in touch with feelings, but the only feelings they tend to be sensitive to and in touch with are their own.” Bingo, Nora. Brando broods over his wounds with nary an ounce of humor. He examines himself with a selective self-awareness that never really faces some very disagreeable aspects of his personality and artistry.

A cursory Google search reveals that Brando left numerous trails of wreckage through the lives he touched. Except for a news clip where he breaks down in tears over the arrest of his son—a genuinely moving moment—we don’t see much honest reflection on his role in the mess his life became. Listen to Me Marlon is billed as an intimate confession, but the subject, true to form, always remains a little out of reach.

This movie is bleak, and the insistent pseudo-classical musical accompaniment only darkens the mood. At the end, Brando recites a soliloquy from Macbeth, “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow.” The solemn, fatalistic reading convinces you that Brando believed that life was essentially worthless. Such a shame.

Leave A Comment