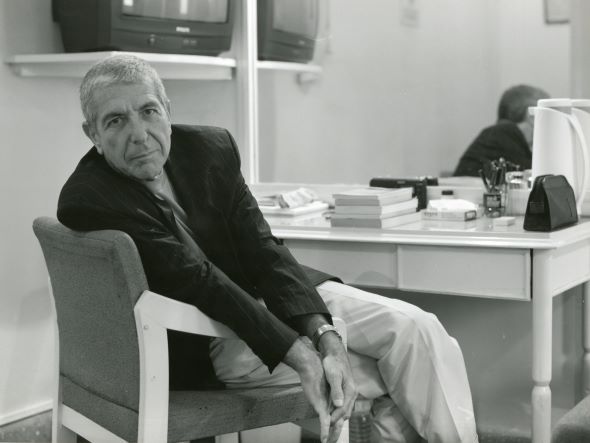

Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song tries and mostly succeeds in being quite a few things at once. At its heart, it’s a biography/appreciation of the great singer/songwriter, but it is also an examination of the now ubiquitous song “Hallelujah”: how it came about, how it evolved, and how influential it became in the culture and why. There’s a lot of heady stuff here, which makes sense because Cohen was no emotional or spiritual lightweight. That the documentary manages to entertain and inform through most of its 115-minute running time is commendable.

It starts not so much with a biography as directors Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine begin at the beginning of Cohen’s musical career, when he was already a renowned poet, as opposed to an initial deep dive into his childhood. They don’t quite ignore his upbringing; they understand that was where the formation of his spiritual self began. His grandfather knew the Torah inside out, and Cohen bragged that if you were to put a pin through the Torah, his grandfather would be able to tell you each word that pin had pierced.

If you are a fan of Cohen or a music geek, there are plenty of fascinating tidbits. Judy Collins, for example, states that he came to her with the lyrics to “Suzanne,” wondering if it had the makings of a song, to which Collins replied yes. He had no intention of becoming a live performer, and attempted to perform the song under duress at a Town Hall gig, but he was overcome with stage fright, so Collins came out and performed it with him, and the song became (also) hers.

What’s fascinating here are the subjects interviewed. Most music documentaries have performers talking about the subject in rapt terms. This one does as well, but it gives equal and perhaps greater time to his rabbi; his best friend since childhood, Nancy Bacal; and a particular journalist he liked, Larry “Ratso” Sloman. This really gives a multifaceted portrayal of a man who is complex at a glance.

Eventually we get to “Hallelujah,” which Cohen wrote more than 150 verses to and pared down to three. Now the film shifts gears and explains how the song came about and practically disappeared from view before it was revived, first by John Cale before its popularity exploded because of Jeff Buckley’s version. The song is from Cohen’s 1983 album Various Position, which was not released in the United States for years—the album version is decidedly different than the popular version. (Vicky Jensen, co-director of Shrek, explains that she took out the “naughty bits” before scoring a scene with it.) The film really delves into what makes the song so universal. Brandi Carlile, Myles Kennedy, and Cohen’s longtime collaborators weigh in on its significance, which is the mixture of the erotic and the spiritual, the essence of Leonard Cohen. And in an example of, I suppose, life imitating art, Cohen himself gets a bit of a late-career revival. Touring for the first time in 14 years, he books a small run in Europe which balloons into a years-long jaunt in venues that were well beyond his grasp previously.

There is some fat on the film, as fascinating as the fat is. A side detour, a mini-bio of Buckley, is long, though illuminating, and then there is a feel-good sequence of admirers, from wedding singers to various American Idols to contestants on The Voice. What Hallelujah gets right, though, is how one person can grok rock and roll and word it so obliquely yet beautifully in song, with the understanding that the basic struggle of man is between the body and soul, the sacred and profane, a battle that usually ends up in a draw.

I’m impressed with this comprehensive review