Leila Hatami & Peyman Moadi in A SEPARATION (Photo: Film Society of Lincoln Center)

The New York Film Festival has gone back to a basic rule: you gotta have a splashy opening night. For programmers, more thought is often put into the selection of this event than any other selection—it sets the tone and defines what the program represents. The status of last year’s opener, the edgy, big-budget The Social Network, was enhanced by its association with the event, a reversal of the notion that studios should be scared by any art-house taint. Instead, it went on to become a box-office hit and a critical favorite. This year, Carnage—directed by Roman Polanski, forever in the news—follows suit, with stars Jodie Foster and John C. Reilly walking down the ubiquitous red carpet. Yet it was only two years ago in the middle of the recession when the festival kicked off with Wild Grass, low on star wattage. Never saw it? It came and went in theaters the following summer. Though a good film, the loopy narrative provoked more huhs than wows. I’m sure donors and sponsors are much happier now. At least, the big names will attract the press.

The programmers have chosen a livelier selection than in recent years, thanks to an expanding programming philosophy and more theater space. Lincoln Center has now two more screening venues after a $41 million renovation. Over its first weekend, NYFF presented the digitally restored 1959 version of Ben-Hur, the epitome of a Hollywood blockbuster (and some would say of its bloated excess). In the past, the festival showcased other refurbished ’50s classics like Vertigo and Touch of Evil, but in no way does William Wyler’s epic share the same esteem among cineastes; I’ve never seen it land in the Sight & Sound best-of list. And making up for lost time, the festival will screen James Ivory/Ismail Merchant’s Howards End as part of a tribute to Sony Pictures Classics. It would be difficult to imagine the last 30 years without the impact of the Merchant/Ivory collaboration. However, their films haven’t been a presence at the annual series since the early 1980s, maybe because their output was seen as too safe, too “cinema of quality.” And though only 10 years old, Hayao Miyazaki’s huge hit Spirited Away will also have an anniversary screening.

Carnage, anything with George Clooney (The Descendants), the instant notoriety of Steve McQueen’s Shame, starring Michael Fassbender and his penis, have already dominated the media spotlight after premiering in Toronto or Venice. Among the hubbub, certainly one to see is A Separation, one of the year’s most engrossing films, directed by Asghar Farhadi from his richly layered screenplay. (It will be Iran’s submission for the foreign-language Oscar.) He sets off the dramatic fireworks immediately in a divorce proceeding, and then the storyline zigzags in unforeseen directions. (Some advice: pay particular attention to what occurs in the sequence following the opening credits.) There’s a lot going on: hostility between a working-class and a middle-class couple; a mother who wants to divorce her unbending husband; a caretaker overwhelmed by her job of taking care of an elderly man with Alzheimer’s; and much more, all elegantly interwoven. Farhadi puts his characters in excruciating circumstances, caught in a web of inferences, half-truths, and loaded omissions. The acting is so intense that you have to wonder how the actors could have filmed some heated scenes in more than one take without succumbing to exhaustion. Farhadi’s second film Beautiful City played in just a handful U. S. cities, if that, and About Elly, one of the best films of 2009, was not released here, even though it had a distributor. (His characters were also painfully put to the test in both.) Fortunately, A Separation will be released in late December.

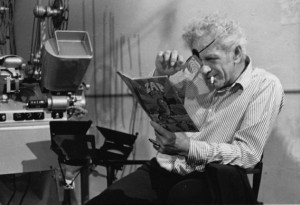

Director Nicholas Ray in WE CAN'T GO HOME AGAIN (Photo: The Film Society of Lincoln Center)

A must-see for film buffs is Don’t Expect Too Much, directed by the late Nicholas Ray’s wife, Susan. It’s a film directing course in a tight 72 minutes. The insights from his former students make this documentary a more thorough examination of a filmmaker’s life than so many director docs. More interested in process than product, Ray taught by doing. He would never be ready to shoot until his actors were prepared, believing in what Charles Laughton once said, “The melody is in the eyes, the words are just the left hand.”

It’s essential to see this companion piece to the restored, relentlessly free-form and split-screen visual bombardment of We Can’t Go Home Again, very much a far-out emblem of its era. It’s a youthquake blown up on 16mm, or any film stock Ray could lay his hands on. He made this experimental and improvised work in collaboration with his students at State University of New York at Binghamton, and the unfinished film hasn’t been seen publicly since its dismal debut at Cannes in 1973. But because of its diffused focus, I would tend to agree with editor Walter Murch, who in Expect, is said to have considered this passion project a mess. The two films will air on Turner Classic Movies later this month, and will be out on DVD in early 2012.

Mostly of interest to cinephiles is the raw, little-seen You Are Not I from 1981 (an asymmetrical haircut gives it away). It was once thought completely lost after a warehouse flood, only to be discovered last year covered in insecticide in Tangier, Morocco, among the estate of writer Paul Bowles. Based on his seven-page story, it was made by DIY New Yorker Sara Drive, then 24 years old, and co-written and shot by Jim Jarmusch. (He also appears in Don’t Expect Too Much, giving good talking head.) Another filmmaker, Tom DiCillo, was the assistant cameraman, and photographer Nan Goldin appeared as a corpse. See it on the big screen, rather than on a small device, which would wash out the grainy, soft-focus black-and-white cinematography. This ghostly film is a reminder when experimental efforts were more integral to the East Coast filmmaking scene.

True, the following film doesn’t have the best title, but Sleeping Sickness represents what the NYFF, or any festival for that matter, accomplishes best: introducing a smart, savvy filmmaker. Shot in Cameroon, the multi-prism film is thoroughly European in its perspective of Africa, the real star, while calling into question Western attitudes toward developing nations. Director Ulrich Köhler spent his childhood in what was then Zaire, and both of his parents were aid workers. However, he says his film is not autobiographical. One of his main characters, German doctor Ebbo Velten (Pierre Bokma), knows the lay of the land (and how to avoid paying a bribe) so well that it becomes increasingly apparent that the good doctor has made a new life separate from his wife and daughter back in Germany. Yet, Ebbo is fully conscious of his outsider status as a white wealthy European. His mirror opposite, black and Paris-born Dr. Alex Nzila (Jean-Christophe Folly), is on the defensive as soon as he lands in the country to evaluate Dr. Velten’s rural money-sapping medical outpost. By the time the film abruptly ends, going native takes on a new form.

Gael García Bernal, left, Bidzina Gujabidze & Hani Furstenberg in THE LONELIEST PLANET (Photo: Film Society of Lincoln Center)

You’ll get lost in the imposing grass-covered Caucasus Mountains of The Loneliest Planet, but its point of view is more of the voyeur than the armchair traveler. With the dramatic scenery as the backdrop, it’s like a series of well-composed snapshots of a relationship hitting a speed bump. Gone is the HD flatness of director Julia Loktev’s first film Day Night Day Night, a sign of how far digital photography has come in five years. Gorgeous American-Israeli actress Hani Furstenberg and Gael García Bernal co-star with the emerald green and lunar landscape as an about-to-be-hitched couple venturing wide-eyed and head-on through the Republic of Georgia’s back roads. Led on a camping trek by Dato (Bidzina Gujabidze, the country’s mountaineering champion), they are model, anything-goes travelers taking in the sights and local culture. The direction is so studied, so understatedly deliberate, that if you turn away at the wrong moment, you’ll miss the volatile turning point, where the otherwise compliant Alex (Bernal) falters. The interaction between the couple before and after the “incident” is rigidly marked so that you can take a barometric reading of their relationship through the widening or narrowing distance between the couple, the long silences, or a small gesture. Loktev lets the events unfold (or unravel) in a gentle, unforced way, seeking no revelations but reveling in the details.

Given that the NYFF is something of an anomaly, with a relatively small number of 27 films making up its main slate culled from major film festivals, audiences are highly likely to have expectations of a “best of” selection. Of course, that depends on how you define “best.” From Argentina, The Student represents an old-school NYFF programming choice, one which will provoke more discussion on why it was included than its individual merits. The simple evolution of Roque (Esteban Lamothe), from blank slate to smooth operator, is weighed down by the imposing and redundant political posturing. The idealistic graduate students speak an insular language (and I don’t mean Spanish). He’s led into the machinations of university elections by his crotch—he’s attracted to Paula (Romina Paula), a strong-willed, uncompromising leader of an also-ran leftist party. Shot on digital video, the good-looking cast often has a ruddy or yellowish complexion. Other selections from Argentina at the recent Latinbeat festival, also programmed by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, had more flair and verve, both visually and in subject matter.

Terrific site, with fresh, innovative look and comment. Thanks.