Film Comment deputy editor and New York Film Festival programmer Kent Jones’s cinematic fan letter to the François Truffaut/Alfred Hitchcock’s collaboration, 1966’s Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock, may be the most effective inducement to pick up a book since Oprah’s Book Club left the air—well, at least for cinephiles.

Film buffs who haven’t touched the acclaimed tome will want to shed their guilt once and for all and read it. For others, this will be an appetite-whetting introduction to the nitty-gritty title and the careers of both French director Truffaut and English-born Hitchcock. However, those who already know the book or have a firm grasp of Film History 101, this documentary will mainly serve as an energizing synopsis.

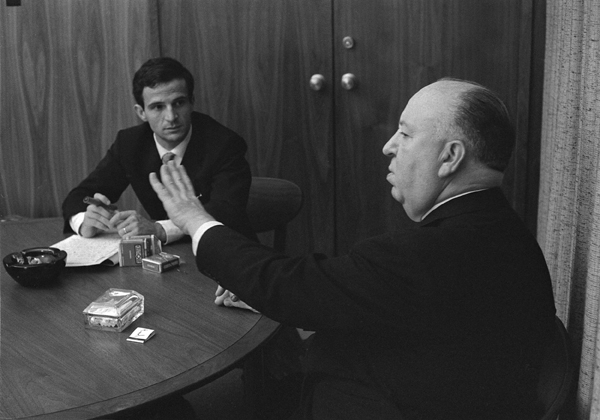

It first traces how critic–turned–trailblazing director Truffaut’s enticed Hitchcock to sit down for eight days for a series of conversations that broke down, shot by shot, selected scenes, which were recorded on audiotape, snippets of which are heard here. An all-boys club of directors chime in on Hitchcock’s style of filmmaking, including Wes Anderson, James Gray, David Fincher, and Martin Scorsese, perhaps the United States’ most effective keeper of the film history’s flame. (What, no Brian De Palma?)

Though many viewers will be familiar with the information presented here, the cavalcade of attention-stealing clips will make them wish more than once for the discussion to stop so they can watch, say, Notorious in its entirety. (No matter how many times you have seen Psycho, the shower scene is a stunner, even if you know that that’s a nude stand-in and not star Janet Leigh under the showerhead.)

Just as Truffaut and Hitchcock dissected in print parts of each of the movies Hitchcock had made up to that point, it’s tantalizing to imagine a long-form Hitchcock overview, something akin to Mark Cousins’s The Story of Film: An Odyssey. There’s too much film lore for an 80-minute documentary, with not enough time to mention Hitchcock’s groundbreaking British works of the 1930s, The 39 Steps and The Lady Vanishes. The documentary dives into only two films in particular, Vertigo and Psycho; each could merit its own behind-the-scenes film. (The former is now proclaimed by Sight & Sound as the greatest film ever made.) Strangely, there’s a bounty of footage of the overripe Marnie, a box office and critical disappointment upon its release in 1964, and nothing from Spellbound, Shadow of a Doubt, or Dial M for Murder.

Granted, director Jones faced a bounty of riches, though it’s strange that the film doesn’t let the actors featured in Hitchcock’s films speak for themselves, such as Bruce Dern, Julie Andrews, and the still-active Norman Lloyd, now 101, to name three. The film does highlight Hitchcock’s often-quoted comment that actors are all cattle, and it’s clear that the editor-turned-helmer saw actors as a way to a means to an end for films that were always storyboarded with visuals carefully choreographed. But he must have been doing something right. James Stewart (Vertigo and Rear Window), Doris Day (The Man Who Knew Too Much), and Janet Leigh (Psycho) all delivered career-high performances under his direction, however minimal it may have been.

Besides actors, Hitchcock dismisses the criticism of his films’ mutable sense of logic. (Guilty as charged: one can’t help think that if Robert Donat in The 39 Steps or North by Northwest’s Cary Grant had just gone to the police, they would have saved themselves a lot of grief.) As Scorsese says with a wink to the camera, a Hitchcock film contains “the spirit of realism,” with a plot that’s “just a line to hang things on.”

However abridged the film may feel, Hitchcock/Truffaut revels in defining the language of film, a lesson that’s easy to pick up. To continue the wonderfully wonky conversation, there’s always the book and, better yet, the films referenced. This tribute was born to air on TCM.

Leave A Comment