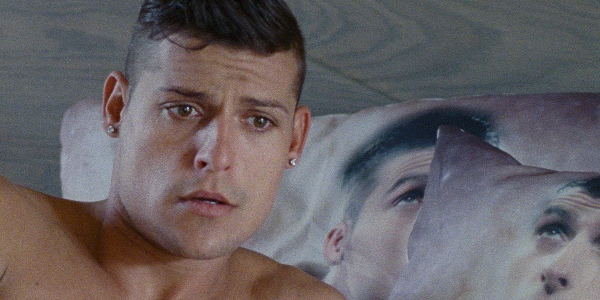

Behnaz Jafari, left, and director Jafar Panahi in 3 Faces (Jafar Panahi Film Production/Kino Lorber)

The latest edition of the annual New York Film Festival is in full swing, and a number of entries in the Main Slate program and beyond are worth noting. The following three films each rank as an artistic achievement and a reflection of the current politics of their respective countries and regions of origin. You can still nab a ticket for 3 Faces and Diamantino, while A Family Tour will likely make the festival rounds post-NYFF. All are worth checking out.

The provocative 3 Faces opens with smartphone footage of a young woman begging for help: her hopes of attending an acting academy have been dashed by ultra-conservative family members who refuse to let her leave home. The pleas of Marziyeh (Marziyeh Rezaei), which culminate in the suggestion that something terrible will happen, are aimed at real-life Iranian movie star Behnaz Jafari and director Jafar Panahi (the two playing themselves), who are so unsettled that they abandon a film in mid-production to go look for Marziyeh in her hometown.

Despite the attention-grabbing beginning, the central mystery takes a backseat to something more akin to a road movie combined with social commentary. A major surprise is that getting to the truth of what happened to the young woman takes less time than we might expect, yet the protagonists are nevertheless stuck in this dry, mountainous, and largely isolated region near the Turkish border, interacting with locals who seem polite enough at first brush. However, what gradually becomes clear is how myopic they are and how much contempt they hold for those who aspire beyond mere utilitarianism—especially if they’re women.

Throughout his career, Panahi has focused on the struggles of women in his home country, where his films have frequently been banned. (Since 2010, he himself has been banned from making films and traveling outside of Iran. This is his fourth film made under such restrictions.) Although 3 Faces views the world through both a male and female set of eyes, the most affecting scenes are the ones filtered through Jafari, who is all too familiar with the insults hurled at the missing woman, having heard similar things aimed at herself. Panahi eventually finds himself faced with the threat of physical harm, while Jafari faces that threat, too, plus the occasional dismissive treatment at the hands of local men. In one scene, a patriarch invites her into his home to ask for a favor: to take home the circumcised foreskin of his only son. It turns out what he really wants is for her to give it as a talisman to a famous male movie star, and if that isn’t possible, any successful man.

Shooting with a handheld camera that only enhances the sense of immediacy, Panahi utilizes long, unbroken takes to build up suspense and also to draw attention to absurdities, such as when motorists must wait interminably at every bend in the road, honking their horns repeatedly before attempting to pass. As a character eventually points out, the men of the village instituted this system, and so it is held as sacred and unchangeable, despite how it increasingly leaves the citizenry unable to move forward and instead forces them to go in reverse. The idea of backwards progress is an unmistakable metaphor.

3 Faces screens on Saturday, October 13.

Ying Liang’s poignant drama, A Family Tour, which is based on the director’s personal experiences, revolves around a mother and daughter who have not seen each other in person for six years. Yang Shu (Gong Zhe) is a filmmaker banned from her native China, having refused to re-edit her last documentary as per the Chinese government’s demands. Her mother, Chen (Nai An), still lives in the Sichuan province, and in order to finally be in the same space, each books a trip to the Taiwanese city of Taipei under different auspices: Yang to attend a film festival, Chen as part of a tour group.

What follows is a reunion, one in which neither side seems free to express their joy. One reason is that the tour guides are constantly watching Chen to make sure she doesn’t try to emigrate with her daughter to Hong Kong, where the latter currently resides. But even during the rare times in which they have some privacy, the mother seems to be holding herself back, causing Yang to worry that she is angry for how difficult life has become as a result of her film. The daughter is especially not sure of how to interpret Chen handing her a recording she secretly made of government officials interrogating her.

A recurring theme is the difficulty of separating the personal from the political, and that is certainly true for Yang, who comes close at times to losing her cool with the tour guides. Meanwhile, the experience of her husband (Pete Teo), a Hong Kong citizen who has accompanied her abroad with their young son, is similar. During his private time, the husband is constantly making drawings that have an effortlessly longing quality.

The film has a tone matching its characters’ reserved natures, and as a result, some of the most powerful moments involve the exchange of a simple, comforting touch. Liang finds ways to lighten the atmosphere: a running joke involves seemingly strangers knowing exactly what the family is up to, even though mother and daughter constantly deny their relationship. This becomes dryly funny after a while, but it also gives viewers some idea of the lengths Chinese families are going to in order to circumvent government policies intent on keeping them apart.

Diamantino, which premiered as part of the festival’s experimental Projections slate, opens with the title protagonist, the world’s biggest soccer star (Carloto Cotta), attempting a penalty kick that could send his home country of Portugal to the World Cup. Then the film delves inside his mind to see how he deals with such intense pressure. The answer: by picturing giant, fluffy puppies cavorting in a haze of pink smoke all around him.

After that bizarre yet whimsical intro, Diamantino, who initially leads a sheltered existence full of yachts and palatial estates, falls hard from his perch as a national sports hero. However, his existence undergoes profound transformation for the better along the way, beginning with his choice to adopt a refugee child as his son. But the boy turns out to be Aisha (Cleo Tavares), a government agent who has been sent to investigate Diamantino for money laundering, and she inexplicably manages to fool him into not realizing she is both a grown-up and a woman.

There is a playful, anything-goes quality to this curious Portuguese-French-Brazilian comedy, but directors Gabriel Abrantes and Daniel Schmidt clearly have a vision, one that involves undermining Diamantino’s masculinity as often as possible. There are countless scenes in which he is browbeaten by his cruel, sadistic twin sisters (played over-the-top by Anabela Moreira and Margarida Moreira), who sell the rights to secretly experiment on his body to a shadowy corporation. In contrast to their aggressiveness, Diamantino is frequently cuddling a kitten or lounging around in his underwear with a thumb in his mouth.

He also unknowingly becomes involved with Portugal’s burgeoning nationalist movement, which has a platform that includes the phrase, “Build the wall.” The faction’s leaders want to use Diamantino as a political prop and spokesperson, but due to the aforementioned experiments on his body, he is no longer the paradigm of traditional masculinity as he previously was. This is where the film is at its most original, seemingly setting up a showdown between the Old World—for which pure blood, pale skin, and chiseled he-man muscles are the most sacred values—versus a brave new one in which sex and gender roles are more fluid. The latter way is embodied by the main character as well as Aisha, who fluctuates between kickass heroine and damsel in distress.

Diamantino might prove too strange for wider audiences, but it’s never boring due to its sheer unpredictability. It also boasts a commendable performance by Cotta, who is physically convincing and who imbues Diamantino with a believable purity and sense of innocence. What also saves the film is its brash attitude toward the current geopolitical climate of Europe, in particular the race-based nationalism that is on the rise.

Diamantino screens on Saturday, October 13.

Leave A Comment