The Wrecking Crew pays fond tribute to the musicians who were behind so much of the rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack of boomers’ lives. It’s even more an insiders’ memoir than 20 Feet from Stardom (2013), that heralded back-up singers, and Standing in the Shadows of Motown (2002), that credited the Funk Brothers house band for the Motown Sound. In the 1960s, eight core members, out of the dozens of such studio musicians, were informally dubbed the Wrecking Crew, and are now in the limelight and treated as part of director Denny Tedesco’s family, literally; his father was guitarist Tommy Tedesco.

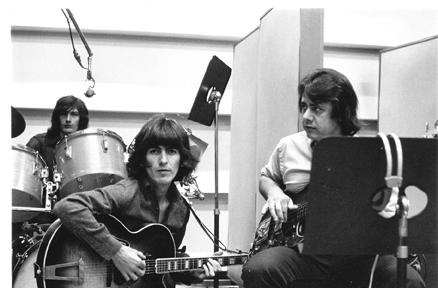

The son started the documentary 18 years ago with a short video about his father’s experiences as a musician-for-hire when the locus of recording the hit parade moved from New York to California and hundreds of classic songs resulted through the early 1970s. Many of the musicians started by playing clubs and recording jazz with Capital Records as early as the 1940’s and ‘50’s. Several of the salty old pros are brought together for a Broadway Danny Rose-type roundtable of trading memories before the separate interviews.

The loose, not completely chronological edit includes legendary producers (Lou Adler), singers, and songwriters, many filmed just in time before they passed away or became too ill, including Tedesco’s father, Dick Clark, and Glen Campbell, who started out as a guitarist in the Crew. (Briefly interviewed, Leon Russell also started out as a bluesy piano player with the backup band.)

The Crew members started out playing with the likes of Nat King Cole and Peggy Lee before moving on to, for the money, the early days of rock ‘n’ roll with Ricky Nelson and the Platters. They caught the wave of the surf sound (orchestrated for up to 20 musicians at a time) by Brian Wilson, the perfectionist behind the Beach Boys, who were too busy touring to record his complicated layered arrangements (most notably on the groundbreaking Pet Sounds in 1966). Wilson still admires how “They could play anything.” Countering a promotional piece touting his family band’s prowess on their instruments, there is rare footage of various Crew members working in the studio with him. They were hired for session after session, turning out four songs in three hours, for a wide variety of stylists, from Sam Cooke to Frank Sinatra to the folk rock of the Byrds. Several headliners shrug about how young and inexperienced they were compared to these professionals.

Trumpeter/producer/executive Herb Alpert describes that the Crew were the Tijuana Brass on his huge selling albums; the famously suggestive LP cover of Whipped Cream was a good distraction from the fictional band. (Milli Vanilli was just the most extreme of a long tradition.) These musicians could read, play complex arrangements, and improv indelibly memorable riffs that the public faces of the bands couldn’t do. The Crew’s role in constituting the famous multiple instrumentalists of the “Wall of Sound” is better known, as those sessions have already been covered in The Agony and The Ecstasy of Phil Spector (2010), and Tina Turner’s turbulent recording experiences with them were dramatized in What’s Love Got to Do with It (1993).

In addition to the extensive biography and clips of the director’s father before, during, and after the heyday of the Wrecking Crew, the lengthy heart of the film consists of warmly avuncular interviews with drummers Hal Blaine and Earl Palmer, who were inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 2001 as sidemen. Blaine is a noted raconteur, and his stories here are more personal than the musical insights Max Weinberg elicited for his book, The Big Beat: Conversations with Rock’s Great Drummers (1984). His legendary, distinctive drum intro in the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” is given a deserving salute. Palmer, as one of the few black musicians in the Crew, has a distinctive perspective, always considering himself foremost a bebop player.

Particularly noteworthy is the attention brought to overlooked bassist Carol Kaye, who has not been seen in other rock ‘n’ roll history documentaries, even those that looked to the founding mothers, like P. David Ebersole’s Hit So Hard (2011) or Sini Anderson’s The Punk Singer (2013), maybe because she represented the antithesis of later rockers who rebelled against such professional musicianship. That’s her bass opening up “Wichita Lineman,” for example. (Will this help get her into the Hall of Fame, which has been slow to induct women from that era?) Kaye is frank that the session work schedule was convenient for a single mother supporting her family.

Others remember working the 8 pm to 4 am shift, until self-contained performing bands lessened the calls for their work. Jingles, TV, and movie scores (the posters and sound bites fly by) helped fill up their schedules, though Blaine is rueful about blowing through his money, wives, expensive cars, and houses from his “10 good years” as he drives around pointing out where he lived and worked in LA. Later, several had (only) the personal satisfaction of releasing solo albums and teaching workshops.

The detailed credits attempt to identify all the session musicians and all the songs they played on, with the help of the musicians’ union, which has made available contracts to prove who, when, and where. There is also a companion book, Sound Explosion! Inside L.A.’s Studio Factory with the Wrecking Crew by Ken Sharp, for yet more specifics and overwhelming chart-topping, Grammy-winning statistics than the many that scroll by.

It’s the excerpts of all those staggering number of hits that energizes this film. (“You Lost That Lovin’ Feelin” is one of the most played songs of the past century, but there’s everything here from the Beach Blanket Bingo theme to Elvis Presley’s “A Little Less Conversation.”) Working out the licensing and proper royalties for the 110 songs on the soundtrack awaited the emergence of crowdsourcing funding to bring this film out of the festival circuit into theaters, as well as other platforms, for deserved and sustained applause. Thanks to this film, the players are anonymous no more.

Leave A Comment