In these pandemic times, watching Austen Rachlis’s lively if earnest debut documentary about the erotic romance publishing industry feels a bit like riding a time machine back to a world that no longer exists (at least for the foreseeable future). There are plenty of shots of crowded writers’ conventions and book parties with fans lining up to have books signed by their favorite authors, ogle the shirtless beefcake entertainment, and grab a giveaway dildo, scenes made even more dated by the annoyingly bouncy soundtrack.

It was only eight years ago (which now seems like a century) that the global success of E. L. James’s initially self-published erotic romance Fifty Shades of Grey shook both traditional publishers and the self-publishing community. The book’s astonishing sales “demonstrated a tremendous appetite for erotica fiction that traditional publishers weren’t aware of and self-published authors were in a position to immediately emulate,” notes New York Times publishing reporter Alexandra Alter.

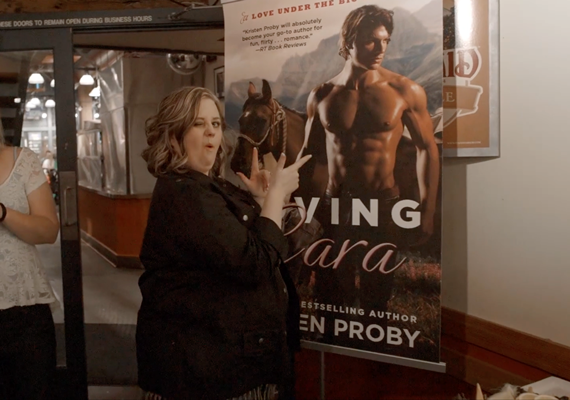

In examining how this long-derided genre became so hot, Rachlis’s film spotlights three writers—Kelli Maine (“Give or Take” series), Kristen Proby (“With Me in Seattle” series), and CJ Roberts (The Dark Duet)—who achieved popularity after self-publishing erotic romances.

As the film opens, each woman has reached a certain level of success and struggles to determine her next steps. Kristen Proby, the self-described “girl who writes dirty books,” chose to self-publish after multiple rejections by traditional publishers, believing that if she sold 100 books, she would be happy. To her astonishment, 1200 copies were ordered the first weekend of her novel’s release. “Seven month later I had a deal with Simon & Schuster, and it was my validation that I should be doing this,” says Proby. She quit her hospital job to write full time, and she recently learned she has sold a million books. The film lightly touches on the financial success some of these authors like Proby have enjoyed. However, Rachlis doesn’t explore the economics of self-publishing in greater detail.

As Proby anxiously prepares for the release of her first traditionally published novel, she chafes at her loss of editorial and marketing control. Meanwhile, Jamie Blair, a traditionally published author of young adult novels, ponders whether to continue writing erotic romances under her pen name Kelli Maine. Her first self-published effort, Taken, was an immediate hit, but her recent novella hasn’t sold so well. Blair/Maine ruefully acknowledges trying to bring more plot into her erotica but finding that “No one wants a whole lot of plot with their sex.”

Another factor is the glutted market and the pressure to crank out a book every few months. “Sustainability is an extremely hard thing to do,” says book publicist KP Simmon, as Blair /Maine discovered. Trying to figure out what her readers want has been a constant source of anxiety for the author. “Do you write what you want to write and have it die on the vine and go nowhere, or do you keep trying to pump the very commercial romance stuff?”

In a mostly white industry, CJ Roberts stands out as Catholic and Hispanic. “In that culture, sexuality for a woman is very taboo,” says Roberts. “Women get turned on too? What would Jesus say?” But her husband encouraged her to publish her story. After 35 rejections from mainstream publishers, she took the vanity press route. “My book ended up on the short list of books to read after 50 Shades of Grey.” But Roberts hasn’t published a novel since 2013 and struggles to find a new story to tell. “It’s been hard to go from writing for fun to writing to pay my rent. I have been given a tremendous opportunity. I feel I am squandering it by not taking the chances that could make me a better writer.”

The film also examines the appeal of this genre to its ravenous fans (one woman went from reading two or three books a year to 88). “What good girl doesn’t want a bad man?” asks another reader. Academic talking heads like Katie Roiphe and Gail Dines debate whether this type of fiction is really liberating for its female readers. Says Roiphe, “There is a retrograde yearning for this traditional man in a traditional role even if we don’t want that in our rational minds; it’s a sign that we are not entirely comfortable inhabiting our own power with ease.”

But sisters Leah and Bea Koch, founders of this country’s first romance-exclusive bookstore, the Ripped Bodice in Los Angeles, vehemently disagree. “These books are written, produced, marketed, and sold for women by women so I find it hard to accept the argument that these books are not feminist,” says Leah. The Koch sisters are so lively and engaging in their passion that they deserve to be profiled in their own documentary.

The failure to address the issues of racism and diversity recently roiling the romance world, including the Romance Writers of America’s decision to cancel its 2020 RITA Awards, adds to the film’s datedness. Still, for romance novices, Naughty Books offers an entertaining, if limited, look at a literary genre too often derided by sexist prejudice.

Leave A Comment