This reverent documentary about Maurits Cornelis (M.C.) Escher (1898-1972) kicks off with a quote from the artist in which he says the only person capable of making a good movie about his work is Escher himself. Director Robin Lutz takes that comment for inspiration, leaning on his subject’s diaries entries, personal letters, and notes. From the start, we get a sense that Escher couldn’t quite comprehend his place in either the art world or pop culture. In his own words, he is baffled—to put it mildly—by his popularity among the counterculture set.

The earliest scenes depict a childhood complicated by physical frailty and anxiety. By the time Escher was attending art school in the Netherlands, he already showed great potential, though two things are made abundantly clear: how impressionable he was to nature and, secondly, his output consistently fell short of his ideas and expectations. His self-denigration persists even after he begins to travel and develop his abilities, particularly sketching and woodcutting, and meets Jetta Umiker, who would become his wife.

Lutz’s strong visual sense complements the subject’s propensity for endless, stream-of-consciousness style descriptions of the what moved him. For example, during a reenactment of a visit to a particular church where the artist frequently found inspiration, we hear him describe the power of the pipe organ and see the ceiling stretch upwards. The shot ends with the camera zooming up into the sky, reflecting how Escher felt his spirit soaring.

The biographical elements are sketchy at times, mainly painting Escher as a caring father and devoted family man who, against the backdrop of the rise of fascism in Europe, made sacrifices and suffered deprivations for the sake of Jetta and their children. This is not to say, however, that it was all misery as one of the more upbeat passages involves his agreeing to a series of illustrations for an Italian tourism company in exchange for a free trip.

He and Jetta subsequently visit the famed Alhambra in Granada, Spain, which proved integral in unlocking what would become Escher’s trademark aesthetic—motifs repeating themselves according to a mathematical system. In what is a relatively straightforward but highly effective lesson, Lutz places the Medieval Islamic art side by side with his subject’s work to highlight how the latter grew out of the former, albeit with Escher replacing geometric figures with images of nature, according to what he called the concept of “recognizability.”

The film’s talk-heavy middle section covers the rich period when Escher was essentially trapped in the Low Countries during War World II, when he turned to creating images from inside his mind. Featuring a montage of some of Escher’s most famous and surreal works (Day and Night), Lutz strikes the right balance between the images and the narration about the intellectual ideas that fueled the art; that is, not too much of the latter. It’s a fine line that Lutz is less successful walking on from this point on, with the film refusing at times to allow the prints to speak for themselves.

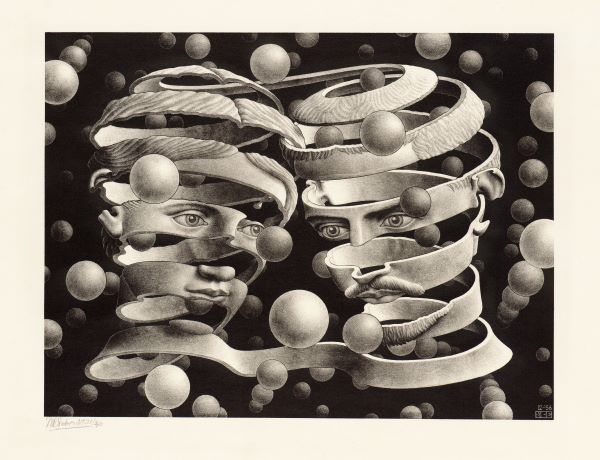

Meanwhile, by making Escher the dominant source of information and commentary, the film comes across as too myopic and in need of other voices. A moment in which one of his sons discusses what happened behind the scenes of Escher’s fascinating portrait of Jetta in Bond of Union proves a welcome change of pace from Escher pontificating ad nauseam.

The filmmakers also made a curious decision by casting British actor and comedian Stephen Fry as the not especially humorous Dutchman, although Fry provides a warmth that offsets Escher’s sober intellectualism. Overall, M.C. Escher: Journey to Infinity credibly captures the life of an artist who is more popular than ever (possibly because reality has become more surreal and dreamlike than ever).

Leave A Comment