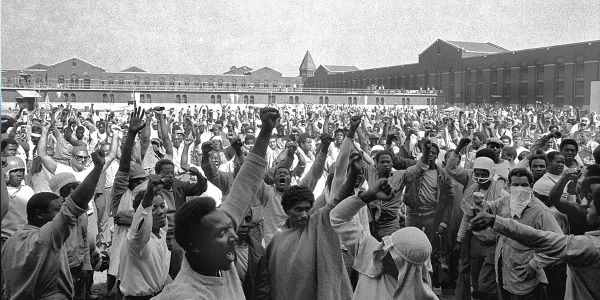

![]() This revelatory documentary recaps events that happened more than five decades ago, which still have the power to induce outrage. On September 9, 1971, the largely Black and Latino inmate population at Attica Correctional Facility staged an uprising in reaction to inhumane conditions, including beatings delivered by the prison’s all-White staff of correctional officers. About 1,200 inmates took 39 guards as hostages, leading to a standoff that lasted for four days until it was put down swiftly and mercilessly.

This revelatory documentary recaps events that happened more than five decades ago, which still have the power to induce outrage. On September 9, 1971, the largely Black and Latino inmate population at Attica Correctional Facility staged an uprising in reaction to inhumane conditions, including beatings delivered by the prison’s all-White staff of correctional officers. About 1,200 inmates took 39 guards as hostages, leading to a standoff that lasted for four days until it was put down swiftly and mercilessly.

A cross section of subjects relive these extremely tense days, including former convicts, the now grown-up children of captured guards, and media who covered the unrest. The breadth of interviewees allows director Stanley Nelson to expand the story of the riot beyond the prison walls. He points to the adjacent and majority White town of Attica, New York, where many of the guards hailed from, as having contributed to the unrest. One interviewee calls it a “great place” to have grown up, but viewers can surmise from the footage how culturally and ethnically homogenous the town was, as well as infer how easy it would have been for those living there to view the convicts as the “other.” The correctional officers are described as using fear to prove they were in control of Attica. Ironically, the guards told their families they were increasingly worried about their own safety.

The first half reflects on the sense of community that sprang up in the yard where the inmates set up camp after the takeover. Through a combination of archived footage and testimonies, there’s the sense that for a brief moment in time, the imprisoned men found a reprieve from their troubles. But Nelson constantly reminds viewers this was a hostage-taking situation, that human lives were hanging in the balance. Meanwhile, one ex-inmate mentions that even with no guards around, everyone had to watch their backs in the yards at night, since some of the convicts were violent and dangerous.

The film spotlights some of the more memorable figures who took part in the rebellion and the subsequent negotiations with the New York State Department of Corrections. They include the charismatic Elliott James “L.D.” Barkley, one of the riot leaders who described the event before television cameras as “the sound and fury” of the oppressed; and Frank “Big Black” Smith, who was in charge of safety for visiting journalists and other outsiders. On the other side of the law is Commissioner Russell G. Oswald, who comes across as two-faced from the start, and thanks to the inmates’ allowing news cameras inside the prison walls, we hear Oswald’s comments changing, depending to whom he is speaking.

A veteran helmer with two Emmy wins under his belt, Nelson takes what might be considered a conventional approach to the material, leaning heavily on talking heads. However, these scenes feature the subjects in close-ups in front of dark backgrounds, a choice that effectively emphasize their scars, both physical and emotional. Also, credit Nelson for never getting in his own way. In an early sequence, the film inserts captions onto a grainy aerial view of the prison, showing where the convicts have set up camp as well as their spatial relationship to the police, who are itching to put down the revolt. It’s one of the few instances in which we can detect Nelson’s hand, which is otherwise invisible.

Attica’s expansive view of the uprising includes snippets from television news reports of the time, which trace a fickle public reaction that turns very much against the protestors as time passes and events turn tragic. As a result, the prisoners find themselves in a race against time to secure clemency from Governor Nelson Rockefeller, whom several interviewees, who were advocates for the inmates, come down on hard for not doing anything to de-escalate tensions at the prison. Eventually, the film revisits what happened as Attica was retaken through the words of those who experienced it firsthand, and the experience is horrifying, though actual photographs from the scene take it to another brutal level that can be hard to sit through.

Apt comparisons are made between the photos and archival illustrations of Africans being loaded onto slave ships, insofar as the dehumanization of their subjects. One could just as easily draw parallels with present-day imagery of majority White police forces quelling protests by Blacks and other minority groups with outsized shows of force and domination. One of the best documentaries of recent years, Attica challenges audiences to stare into the abyss of another era and see ourselves reflected back.

Leave A Comment