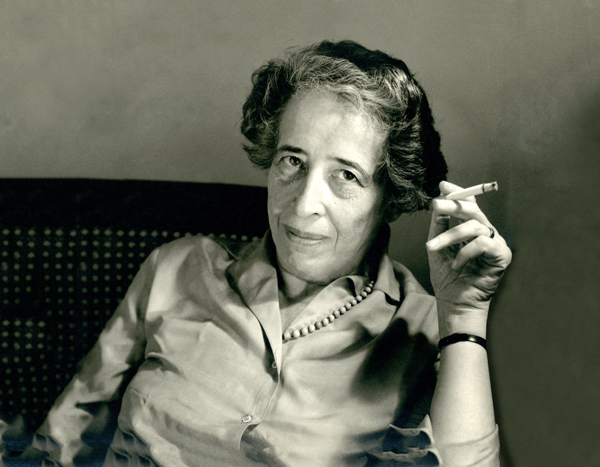

Born in 1905 during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm in 1906, Hannah Arendt emerged from a continent pummeled by ideological storms to become a leading philosopher of politics. She brought her contemporary reality to bear on historical analyses in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), The Human Condition (1958), On Revolution (1963), and Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), the latter of which introduced “the banality of evil” to the popular lexicon (to describe functionaries who are just following orders).

In the very detailed Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt, Israeli documentarian Ada Ushpiz applies the feminist argument that “the personal is political” to Arendt’s life to understand her perceptions and to provide context for the controversy over Eichmann. Through a barrage of expert academic talking heads, plus Arendt’s former colleagues and students—as well as excerpts from private diaries and letters, radio and TV interviews, and visually much more—Ushpiz presents her subject as a German first, a woman second, and then a Jew. However, it’s the last that provided the inconvenience that forced Arendt to flee Germany and the men she cared about.

Though told in more or less chronological order, Ushpiz occasionally circles back to the past for explanations as to Arendt’s later actions or opinions. Arendt’s childhood, in which she was completely a secular Jew integrated into middle-class German society, proves useful in understanding how she became a precocious intellectual. Meanwhile, the loss of her father and grandfather by age seven may explain her close relationships with much older male academic mentors, including the married Martin Heidegger, her first university professor and soon-to-be intimate. The film explores their relationship and includes their love letters, but it does not gloss over his accepting a prominent university position with the support of campus Nazis, which occurs at around the same time she is arrested for investigating rising anti-Semitism for a Zionist organization.

While Vita Activa has a lot to say about its subject’s life and times, it doesn’t shy away from the trickier or more controversial moments. One of the film’s more compelling chapters concerns Arendt’s letters to Karl Jaspers, her dissertation adviser and an important mentor, in which she writes about trying to rationalize Heidegger’s actions. (Left undeveloped is if Heidegger can be considered Arendt’s first model of careerist “banality” under the Nazis.) Richard Bernstein, philosophy professor from the New School for Social Research, points to Arendt’s criticisms about the misused powers of the appointed Jewish leaders under Nazi control as having received the loudest condemnations from the Jewish community. Unfortunately, her analysis was based on incomplete information, according to Bernstein. More passionate and specific ripostes were provided by Benjamin Murmelstein in his lengthy interview with Claude Lanzmann in The Last of the Unjust (2013).

In interviews, Ushpiz said she hopes Arendt’s legacy will be a form of moral politics that is not based on rigid ideologies or closed thinking. To that end, Vita Activa is a film about more than just its subject’s philosophy but the experiences that formed her.

Vita Activa: The Spirit of Hannah Arendt is recommended as a thoughtful companion to Margarethe von Trotta’s 2012 Hannah Arendt, which portrayed her later life and work in New York.

Leave A Comment