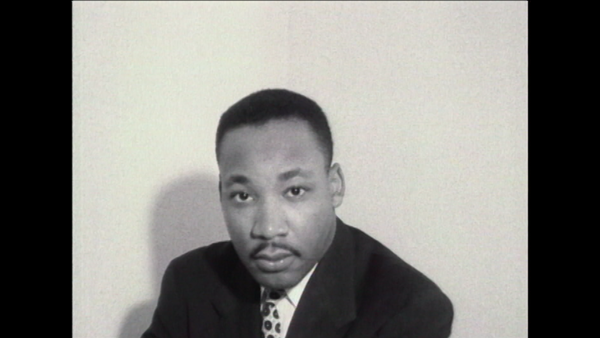

Director Sam Pollard lays out a sharply detailed time line of how the Federal Bureau of Investigation used its resources to target civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in the mid-1950s, first as a suspected dupe of the Communist Party USA, before it deemed him “the most dangerous Negro in America” shortly after 1963’s March on Washington.

A large portion of this fact-driven documentary covers the 1960s, during which time King increasingly opposed the Vietnam War in public. However, the film also points to the lingering Cold War as a factor in the FBI’s growing antagonism toward King, who first landed on the agency’s radar through his right-hand man, Stanley Levison, who had associations with communist groups. (Levison remains a shadowy figure, with little mention of the attorney’s background or the sort of counsel he gave King.)

The filmmakers illuminate, if that’s the right word, how the FBI discovered King’s extramarital affairs through the tapping of the phone of King’s speech writer (attorney Clarence Jones) and deployed them as blackmail fodder. The FBI reportedly bugged 15 hotel trysts, sometimes with agents in the room next door. Yale historian Beverly Gage frames the motivation of its longtime director, J. Edgar Hoover, within the context of the era, and she ever so lightly touches upon Hoover’s personal life and readily admits that his biography warrants a longer discussion. Elsewhere, Pollard refrains from an armchair analysis of Hoover’s oft-discussed sexuality.

Pollard’s film will fill in many of the blanks that were intimated in a major subplot of Ava DuVernay’s Selma (2014) and Clint Eastwood’s simplistic take on the FBI chief in his 2011 biopic J. Edgar. Additionally, Pollard makes up for the insinuations in DuVernay’s takedown of President Lyndon B. Johnson: LBJ is not mentioned as part of the plot to humiliate the married Baptist preacher by sending the surveillance tapes to the reverend’s wife.

As Pulitzer Prize–winning author David J. Garrow points out, the FBI didn’t need to coordinate with the Johnson White House, as its distrust of King dated back to the Kennedy administration. The film also asserts King had a closer relationship with Johnson than Selma implied. Rather, it reveals that President John F. Kennedy and his attorney general, Robert F. Kennedy, approved of the FBI’s wiretapping of King under the suspicion of sedition and subversion stemming from his continued association with Levison.

Pollard eschews talking-head interviews while still identifying who’s speaking during the propulsive voice-overs. Visually, he relies on a trove of archival footage circa 1955–1968, from King appearing on Meet the Press to a Red-baiting Governor George Wallace, although there is perhaps an over-reliance on B-movies, like the hoary I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951). Yet according to Rutgers University history professor Donna Murch, the films were all part of the media’s overwhelmingly positive representation of the law enforcement agency, and at the very least, the viewers’ eyeballs never tire.

Going against the grain of a social media thread, the film is less interested in taking down celebrated figures or easy targets than putting them in a more rounded, complicated perspective. Certain figures may come off as problematic or less pristine as a result. Supporting its viewpoint are recently unearthed documents that have been unclassified, although the research remains an ongoing story. Any lingering questions regarding King’s private behavior, including an especially alarming allegation, may not be answered until 2027, when the FBI’s surveillance tapes are scheduled to be made public.

MLK/FBI will be released in early 2021 by IFC Films.

Leave A Comment