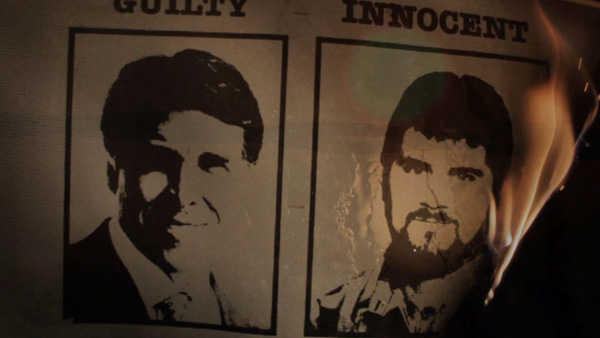

A scene from INCENDIARY: THE WILLINGHAM CASE (Photo: Indie Film/Yokel)

Produced & Directed by Steve Mims & Joe Bailey Jr.

Released by Truly Indie/Yokel

USA. 102 min. Not rated

A courtroom truism is when the facts are against you, argue the law, when the law is against you, argue the facts. But when a documentary about injustice piles on the facts, it still needs to make a cinematic case. However, Incendiary: The Willingham Case mostly updates a 2009 New Yorker magazine article about a father’s capital conviction for the death of his three little daughters in a house fire on December 23, 1991.

The date is important because just a few months later the National Fire Protection Association issued its first scientifically based guidelines for arson investigation, too late for the father, Cameron Todd Willingham. His misfortune at being charged with arson homicide was greatly multiplied by living in a northeast Texas town, in the state with the highest number of executions in modern American history.

Directors Steve Mims and Joe Bailey Jr. open the film with long explanations by two experts in fire and arson determination. They are only vaguely identified until their considerable renown and personal involvement on behalf of the defense are explained quite a ways into the film. As talking heads, one looks like a buttoned-up lawyer (John Lentini), the other like a long-haired, bearded mad scientist (Dr. Gerald Hurst). But as they step-by-step examine this fatal fire, illustrated with a few photographs of the blackened scene and close-ups of the report from the local fire department, the screen distractingly fills over and over again with mesmerizing, overpowering images of fire, visually drowning out their intricately complicated reasoning about why this was never, in fact, an arson. This was also the same year as Ron Howard’s Backdraft, a feature film that vividly extolled arson investigation as an artful knowledge of fire, the very approach these earnest scientists scoff at as “witchcraft.”

Distressingly, Willingham’s court-appointed lawyer does not believe in his client’s innocence, swayed not only by other experts’ testimony, including a later disqualified psychologist’s diagnosis, but what he claims the wife-beating defendant said to him that is subject to attorney-client privilege. With shades of Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night (1967), the film emphasizes that small-town police and fire departments are not up to big city standards, and then shifts jarringly to the heart of the matter as it turns to anti-death penalty activism. Since Willingham’s execution in February 2004, his conviction has become the test case for the Innocence Project, which usually focuses on DNA-based exonerations to counter Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s scoff that nowadays there is not “a single case—not one—in which it is clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit.” (David Grann’s original article was called “Trial by Fire: Did Texas Execute an Innocent Man?”)

The directors follow the Project’s efforts to reopen the case and get caught up in how state politics affects the legal process, focusing on Governor Rick Perry and his appointees to various law enforcement and investigative positions. The pettiness of typical local politics trumping science, including manipulation of procedures such as open meetings regulations (well captured on camera when the directors are removed then permitted into a hearing), would seem aimed at the 2012 presidential election if people’s lives on death row weren’t at stake. Unfortunately, Innocence Project co-founder Barry Scheck, in his understandable frustrations, comes across as the antagonistic New York lawyer that the locals paint him. Oddly, it’s left to the scientific experts to try and explain how their crucial evidence couldn’t fit into Willingham’s appeals and reviews, but helped in other similar cases. The directors tread sympathetically around Willingham’s ex-wife’s changing views of his guilt over the years in order to represent the victims of what was probably a horrible accident.

PBS’s Frontline has been conducting an ongoing investigation of the poor quality of forensics around the country, and will doubtlessly be able to afford better graphics and clearer explanations when it looks later this month at the arson controversy, particularly this same tragic case.

Leave A Comment