Among the tributes honoring the centennial birth of Merce Cunningham is this 3-D documentary highlighting the career peak of the legendary choreographer.

Russian-American filmmaker Alla Kovgan tracks Cunningham’s years as a struggling dancer and his evolution into one of the world’s most innovative and important choreographers. In her captivating film, archival footage, reenactments, and interviews create a montage of Cunningham’s groundbreaking work from 1942–1972, the stretch that sealed his reputation as a master of the form.

Similar to the 3-D effect in Wim Wenders’ 2011 dance documentary Pina, the added dimension that comes from wearing 3-D glasses immerses the viewer beyond the usual flat screen of recorded performance, while adding the novelty of modern technology to the historical dances. As cinematographer Mko Malkhasyan’s camera swirls and plunges, one has the sense of being among those on stage.

Cunningham expresses his philosophies in sound bites and clips. “I don’t describe it. I do it,” he says, and he refuses to label his work with terms such as “avant-garde,” although others categorize it as such. His early studies in ballet gave him leg strength, and his training in Martha Graham’s modern technique yielded flexibility and power in his torso. Combining these disciplines allowed for as many movement possibilities as he could conjure, which lead to his unique style.

Kovgan selects excerpts from 14 dances, led by Merce Cunningham Dance Company mainstay Jennifer Goggans, to represent the oeuvre through restagings, within the 90-minute runtime. Venues include high-rise rooftops, an airline terminal, a forest, and a tunnel.

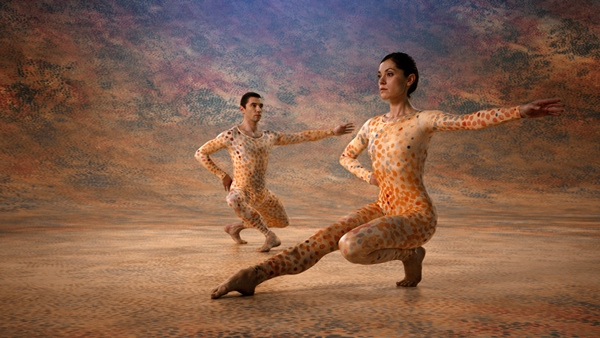

Among them are RainForest (1968), inspired by a flora and fauna filled environment in Cunningham’s childhood home in Washington State, and enhanced by costumes with cutout holes designed by Jasper Johns and silver pillow balloons by Andy Warhol. Summerspace (1958) features a myriad of turning dancers in hand dyed bodysuits and a matching pointillist backdrop that blends in with the ensembles, all by Robert Rauschenberg.

Contemporaneous interviews of Rauschenberg, as well as composer John Cage (Cunningham’s professional and life partner) illuminate this era of collaboration. Cage’s influence brought happenstance and chance to Cunningham’s methods, calling on dancers to improvise sequences and steps determined by the throw of dice or The I-Ching, the ancient Chinese book of divination. Critics called the approach inhuman, because the choreography was controlled by inanimate objects, yet it was just this kind of risk taking that resulted in Cunningham’s visionary stance.

Missing from the film are the kind of biographical details that could flesh out the story of such a significant artist. That, along with the lack of context of his choreography within the world of dance, keeps Cunningham from becoming a fully rounded introduction for general audiences. Nevertheless, for those who are already familiar with the man and his work, or who want to whet their appetite for a key figure in dance history, the fundamentals and landmark performances are here to enjoy and be immersed in.

Leave A Comment