At the 62nd edition of the New York Film Festival, we once again find ourselves at an important annual stop to consider new contributions to cinema. Many of the most publicized titles already have planned commercial release dates in the upcoming months, so it’s worth taking time to recommend standout films that are still awaiting distribution midway through the festival.

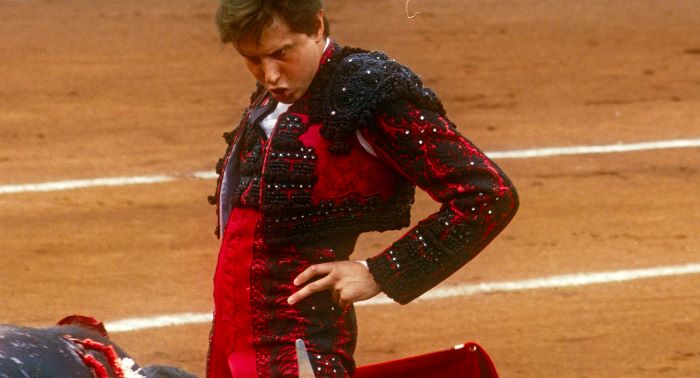

One film that shouldn’t take long to find a suitable distributor more aligned with art-house fare is an immediate highlight of this year’s lineup: Albert Serra’s Afternoons of Solitude (Tardes de soledad), the recent Golden Shell winner at the San Sebastian Film Festival. His new film shares practically nothing—not even language—with his previous work (the mesmerizing, French-language Pacifiction), but it once again highlights this unclassifiable director’s untamed and fearless spirit. You can always count on the Catalonian enfant terrible to deliver work that engages both the mind and the gut. The patient, omniscient documentary approach to a real-life matador, Peruvian-born Andrés Roca Rey, doesn’t mean Serra will be any less wild or sensual in his approach. However, you’ll need a strong stomach to appreciate it.

Afternoons of Solitude is a contemplative exploration not interested in addressing moral qualms around the controversial sport of bullfighting, even if you can’t avoid questioning to what extent Spain’s heritage/culture is a valid excuse for cruelty. A warning: If you are extremely sensitive about animal abuse, there are plenty of shots of bulls being stabbed and killed and instances in which the matador is close to death. On top of that, there are also horses with blinders involved, used as shields against the bull’s horns. Every corrida (bullfight) almost plays in a business-as-usual way, even tedious after repetition becomes the norm: the dressing of the matador, the shuttle to the arena with his crew, and multiple intense sequences in the bullring, in which bulls always end up sacrificed.

Part of its spell relies upon how the camera also chases the rapture, the rituals before the fights (the matador slowly putting on each piece of his attire can be more erotic than any naked actor’s body or sex scene), and the adulations after (an almost Greek chorus accompanies the matador, describing each corrida as an absolute triumph). The camera portrays Roca Rey as an inscrutable sphinx ready to live and die for what the public is thirsty for. Hero and fool at the same time, the torero makes a pact with death, and you never know when the debt will be collected. At times, you can almost understand why this weird carnage-as-entertainment event conjures something unattainable that can almost be deemed as a primitive form of art and performance.

In the current market, documentaries may wait a little longer than features before finding a distributor. This is even true for well-known directors like Petra Costa, with her eloquent and urgent new documentary Apocalypse in the Tropics. Partly a follow-up to her Oscar-nominated The Edge of Democracy (2019), Costa this time specifically focuses on the progressive rise of the evangelical church in Brazil and its political influence that has aligned with far-right parties. With persuasive rhetoric and an alarming tone, Costa makes a case that serves as a warning for other countries where religious groups gain political power to influence democratic processes and even plant a seed for their destruction (United States voters can take note).

In Brazil, 30 percent of the population follows the evangelical faith, while the leadership of these groups is represented by pastors who actively participate in the country’s political life (including television programs and seats in the Senate). Among them, you’ll find televangelist Silas Malafaia, who does not hide his anti-abortion and anti-LGBT rhetoric, as he asserts his right to freedom of expression. He also openly plans to dismantle the secular state to counter the same freedom that allows him to promote hate speech. In many ways, he was responsible for Jair Bolsonaro’s election as president, a far-right leader aligned with the evangelical agenda. He campaigned for Bolsonaro and warned how far from salvation Brazilians were if a God-appointed leader was not chosen soon.

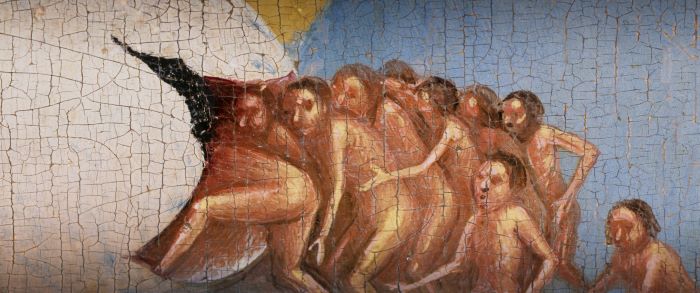

In addition to exploring the country’s religious history, the documentary is committed to scrutinizing evangelical philosophy and the scriptures that support such ideals, as the Book of Revelation becomes a fundamental text to understand the movement. Costa paints a Bruegel-like immersive landscape of doom and gloom that suggests she’s more disillusioned than ever with the pro-Lula biases of her last film. The once-convicted, re-elected president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, remains a spokesperson for the Latin American left, but is now, strategically, willing to show greater sympathy toward the movements that contributed to his temporary arrest. (“Communism made a mistake in excluding religion,” he expresses.)

The documentary is an urgent exposé about the anti-democratic spirit willing to accelerate the end of the world in the name of God. However, the alarmism could be moderated with more nuance and a bit more doubt and hope, especially regarding the history and idiosyncrasies of countries like Brazil (and to some extent, all of Latin America, constantly bouncing back and forth between extreme right and left).

Writer Antonio Benítez Rojo, in his book La Isla que se repite (The Repeating Island), questions how much the idea of the apocalypse could resonate in Caribbean and tropical settings: “The Caribbean is not an apocalyptic world … In Chicago, a tormented soul says ‘I can’t take it anymore,’ and turns to drugs or the most desperate violence. In Havana, one would say: ‘What we must do is not die,’ or perhaps, ‘Here I am, screwed but happy.’” The warning is valid because, yes, democracy is fragile, and it’s imperative to protect it. However, there is another Brazil, part of the other 70 percent, where Carnival remains the most anticipated celebration and Madonna can break audience records with a free concert on Copacabana Beach.

The Edge of Democracy was distributed by Netflix, which could be the perfect home for Costa’s latest so that her important message can reach a large audience.

Meanwhile, another international work awaiting distribution is one of the most unusual finds in the festival, the autobiography of a hippo, Pepe, by Dominican director Nelson Carlo de los Santos Arias. The director’s previous feature (Cocote) already introduced him as a filmmaker capable of creating arresting images, even when stifled by his esoteric narrative. The hallmarks of his style reappear in his new film, though with a more self-aware sense of absurdist humor, complete with the real-life events that underpin it. De los Santos Arias joyfully follows what writer Alejo Carpentier would describe as the manifestation of “lo real maravilloso” (the marvelous real, which is not the same as magical realism).

Telling its story as a ghost aware of its own death, Pepe’s cavernous voice is expressed in different dialects and languages throughout, depending on where each episode of his extravagant story takes place. The hippo became a local legend in Colombia as one of the animals exported for the private zoo at Hacienda Nápoles, owned by drug lord Pablo Escobar. After Escobar’s death, Pepe the hippo found emancipation, escaping his original confinement and becoming a beast that terrorized fishermen along the Magdalena River for years. During a guided tour in Africa, in one early sequence, we are told how hippos sink boats by moving underneath them and pausing before making their next violent move. Of course, this is not an animal suited to an environment like Colombia, and the locals naturally consider it a threat to the point where they organize a group to hunt it down.

It’s a tumultuous story for a single hippo, and this is exactly what de los Santos Arias represents across two hours (some biopics of humans are shorter, even with much more life material to draw from). Still, Pepe boasts an attractive unpredictability, along with some stunning shots that many renowned cinematographers would kill for. There are some tangential reflections on colonialism, and in part, Pepe can be read as a symbol of a migrant adapting to a foreign land. It could also be seen as a visual joke stretched a bit too long.

Leave A Comment