To address dark episodes in a country’s history, it’s insightful to explore how these tragic events directly impact families and individuals. This approach helps transform history into a pulsating, lived experience. That’s exactly what I’m Still Here achieves, the new film by Brazilian director Walter Salles, as it intimately delves into the wounds and injustices committed in Brazil during its military dictatorship (1964–1985), focusing on the real-life disappearance of Rubens Paiva and, more importantly, the direct consequences on his grieving family. Through a carefully structured linear script that spans over 40 years (from 1971 to 2014), the film initially paints an enviable postcard of a happy family enjoying a sun-drenched tropical paradise.

On the beaches of Rio de Janeiro, former congressman Rubens (Selton Mello) and his wife, Eunice (Fernanda Torres), share a summer afternoon with their six children of various ages, from the daughter about to start college to the two mischievous younger ones. Their biggest concern is convincing their parents to let them adopt a stray dog (the parents can’t resist and give in). The chemistry between the couple is so palpable that it wouldn’t be hard to imagine them having six more kids if they had the chance. But the sky isn’t as bright as it seems, and subtle signs progressively reveal that circumstances are far from well or safe for anyone paying attention to their surroundings.

The hasty decision to send the eldest daughter to study abroad, news of kidnappings by terrorist groups, and brief glimpses of dread whenever an armed patrol passes by are situations that speak for themselves. Eunice, a keen observer, carefully notes the small gestures and signals worth being alert to, including sudden visits from strangers to see her husband. The couple occasionally talks against the regime among friends, in a very private environment, but they are not exactly activists. So, they are ultimately caught off guard when an armed group, possibly undercover military, temporarily holds everyone hostage in the Paiva household, after which Rubens is taken away for interrogation. When the intruders finally leave the Paiva home without providing clear answers about the man’s fate, Eunice embarks on an excruciating odyssey to find answers and emotional closure that will define the rest of her life.

I’m Still Here is a painful chronicle that would be unbearable if not anchored by a central performance that goes beyond suffering. It instead showcases Eunice’s stoic defiance, bravery, and stubbornness in refusing to succumb to loss. Other family members have their own crises, and there’s room for a wide range of reactions properly explored in time, but Eunice remains the narrative anchor. Fernanda Torres is a blazing presence, with a stern disposition that reveals fascinating nuances at every turn, making hers one of the best female performances of 2024. She embodies a character distinguished by her internal struggle to keep her family afloat, simultaneously masking the scars of having witnessed horror up close.

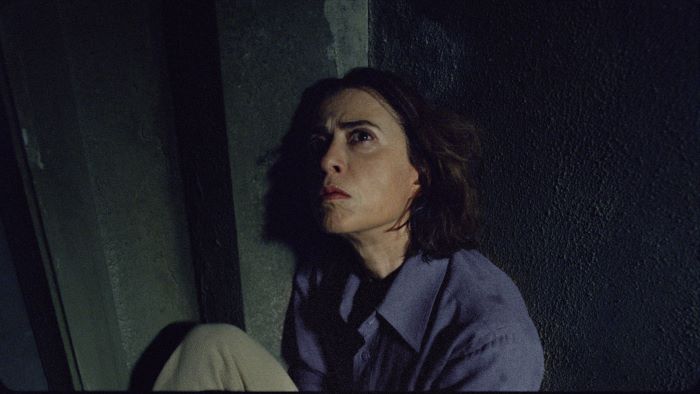

After her husband’s disappearance, Eunice is detained for weeks and interrogated daily about what she knows regarding her husband’s connections to revolutionary groups. This section creates briefly, albeit effectively, a tense prison drama that underscores the extent to which authoritarian governments are capable—turning the life of an ordinary citizen into an endless nightmare.

Another key sequence depicts Eunice gathering the remaining family for a photo-op to appear in international newspapers. She urges them to smile for the camera, although the photojournalist insists that they look sad, given their circumstances. The Paiva family probably wouldn’t have survived amid the constant paranoia of being under surveillance and the uninterrupted psychological torture if they didn’t know when and why to smile as a form of resistance. In part, I’m Still Here unfolds like a memory told through a photo album and the secrets behind the images (and those smiles).

Visually, Salles constructs a conventional drama that doesn’t stray from the classic narrative conventions of historical sagas. The legendary Fernanda Montenegro (mother of Fernanda Torres) plays the older Eunice in a brief coda, delivering a moving performance that also reunites her with Salles decades after Central Station (1998). In fact, one could argue that this is the director’s best film since that unforgettable collaboration.

Politically, the past portrayed here remains poignant and relevant as a message for the rest of South America, where a new dictatorship is always just around the corner whenever democracy is neglected. One family cannot change a nation’s past, but it can become the most reliable narrator, bringing history truly to life beyond the cold, clinical facts.

Leave A Comment