After a year and half of curtailed moviegoing, the 2021 all in-person New York Film Festival was like going back to the recent past. It featured several elaborately produced films that, as seen on the big screen of Alice Tully Hall, overwhelmed and washed over viewers: Dune, with its enveloping sound design; the visceral Titane; and Wes Anderson’s latest, the visually dazzling and exhilarating The French Dispatch.

All were undeniably made for theaters and a reminder that in many cases, schlepping to the movies is the best way to experience them as fully as possible. In Anderson’s contribution to the festival’s razzle dazzle, the visuals push its multiple stories forward, constantly stimulated the viewers’ eyeballs.

The film’s titular, and fictitious, weekly magazine began publishing in 1925 as a Sunday supplement on “fancy cuisine” for the “Kansas Evening Star,” and it continued to bring France to the Midwest until the mid-1970s. If writer Janet Flanner, the Paris correspondent for The New Yorker, comes to mind, you are in the right headspace. Anderson gives special thanks in the closing credits to her and other New Yorker contributors, such as its founding editor Harold Ross, and a slew of writers—James Baldwin, Lillian Ross, S. N. Behrman, and others.

It’s 1975, and editor-in-chief (Bill Murray) presides over the very last issue. Frowning grammarian, Alumna (Elisabeth Moss), and other editors crowd his office to finalize the overstuffed issue before deadline: cuts have to be made to three featured stories, all of which unfold on screen.

They take place in the not-so-subtly named Enni-sur-Blasé, a stand-in for Paris or any other Hollywood French fantasy. First, as in a sidebar, a bicycling Owen Wilson gives the audience a tour, pointing out the lay of the land, from the city’s rats in the sewers to the cats on the roofs, the maundering choirboys, and the whores and hustlers by the riverfront after dark. Cue the Satie–esque musical score by the prolific Alexandre Desplat (who else?).

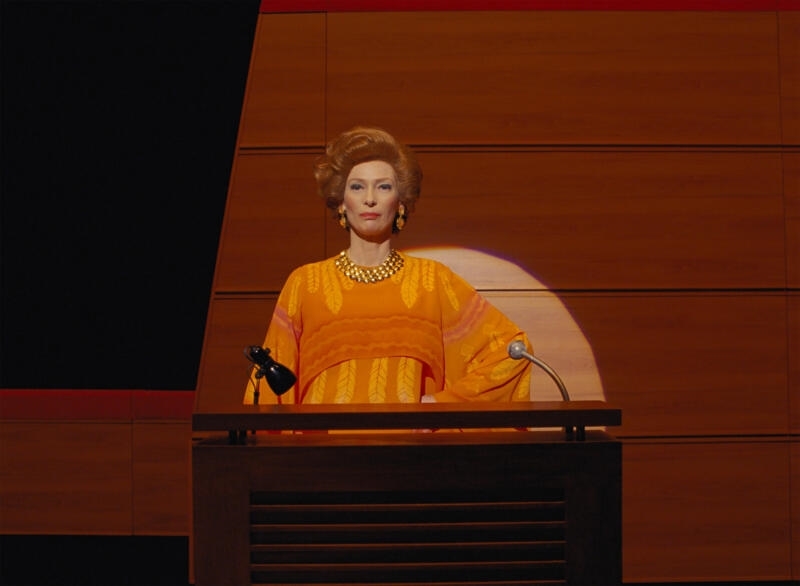

An insane and homicidal prisoner becomes the darling of the art world with his envelope-pushing abstract paintings in the first tale, in the issue’s “Arts & Artists” section, narrated by Midwestern modern art maven J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton). Léa Seydoux, as a stern jailhouse officer, poses as the model—and muse—for the convict, played by a growling and stoic Benicio del Toro.

The turmoil of May 1968 forms the backdrop for the second jaunty tale, centered on the sardonic (once again) Frances McDormand, as “Dispatch” staff writer Lucinda Krementz, the only adult over 30 who can understand the youthful rebellion that has shut down the city. As its plot takes sudden turns, so does the film’s aspect ratio, which expands here to widescreen. Sure enough, there’s a tip of the beret to Jean-Luc Godard’s Bande à Part in a café scene, one of Anderson’s most apparent homages to French cinema.

The third piece enters on author Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright, with the pitch-perfect vocals of Orson Welles) recounting on a TV talk show his encounter with Blasé’s criminal underground. This is the only tale that has the obligatory nod to French cuisine, as the chef to the police commissioner, Lieutenant Nescaffier (Steve Park), saves the day.

What is delightful and captivating is the journey, and not necessarily how the three stories—yarns, really, as opposed to the provocative and investigative pieces that The New Yorker is noted for—end. It’s like each episode expands an anecdote from “The Talk of the Town” section, filtered through Anderson’s kaleidoscopic lens. One could say that he only figuratively celebrates the cerebral wit of the real magazine. The dialogue is droll, but the humor largely lies in the action, which verges on the slapstick. Everything here, from the onscreen character quirks to the escapades, could be considered twee. Even so, the consistent and fluid tone always stays light on its feet.

The best way to bone up before seeing The French Dispatch isn’t to pick up an issue of The New Yorker or to take a Pauline Kael deep dive (though I’m sure it wouldn’t hurt). If you need any preparation at all for the Anderson avalanche of whimsy, it is to binge on silent movies. Though this film celebrates French culture, the production design (recalling the geometrical sets in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis or King Vidor’s The Crowd), the use of miniature sets, and the overall exuberance owe a lot to the anything goes, free-wheeling visuals of early silent movies. Perhaps the debt to silent cinema is more pronounced in this, Anderson’s tenth film, because large portions of it are shot in black-and-white. You never know when splashes of color, and even an animated sequence, will hit the screen.

As is frequently the case in Anderson’s work, his repertory of actors is cast according to type, although Saoirse Ronan makes a surprise appearance as a junkie showgirl involved in a kidnapping caper. A great addition to the ensemble is Lois Smith, as a no cuss, no fuss art collector of the Great Plains. While the actors are not required to stretch their acting muscles, they have fun, and it’s infectious. (How many opportunities do they have to take part in a tableau vivant?)

The exteriors were filmed in Angoulême, France, but the film makes a strong case for creating worlds on a sound stage. Given Anderson’s big-name cast, his latest should be an art-house event this fall; he has concocted a buoyant bouillabaisse.

Leave A Comment