Can a work of art so closely tied to a particular tragedy transcend its era to speak to future generations? This beautiful and moving documentary by Rosalynde LeBlanc and Tom Hurwitz resoundingly says, “Yes.” Unlike other recent films, such as Wim Wender’s Pina (2011), Alla Kovgan’s Cunningham (2019), and Jamila Wignot’s Ailey (2021), which highlight their choreographers’ body of work, the main focus here is on Bill T. Jones’s 1989 ballet D-Man in the Waters, now considered one of the most important artistic works to come out of the AIDS epidemic.

“I became a dancer when I saw D-Man in the Waters when I was 16 years old,” says filmmaker LeBlanc in a voice-over. Now an associate professor in the Department of Dance at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, she joined the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company at 19 and danced the piece around the world. “It’s the most grueling dance I have ever performed, but it’s also probably the most exhilarating.”

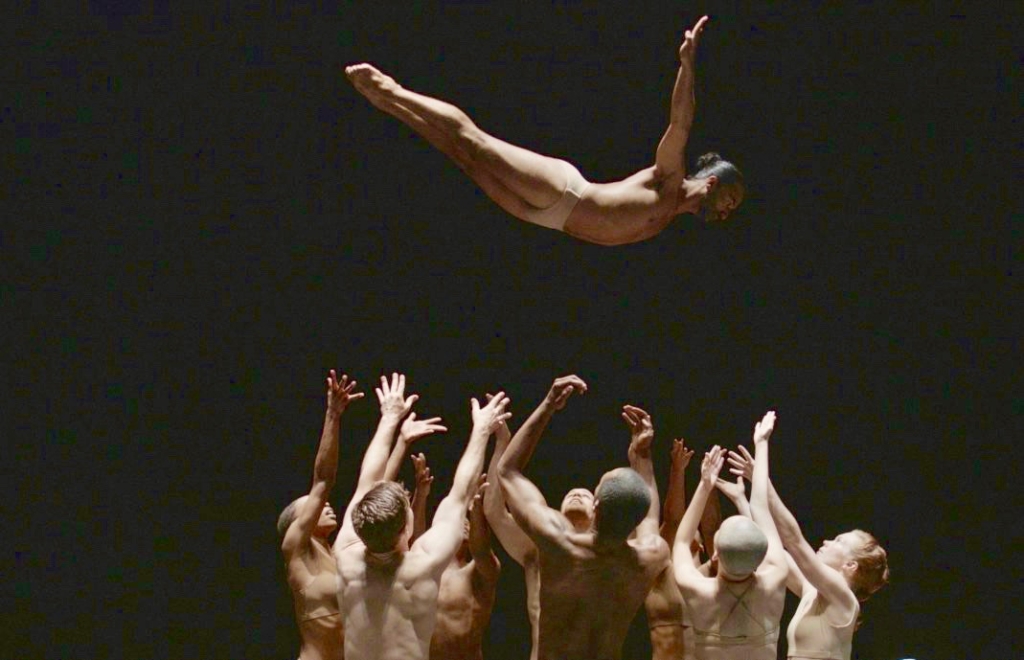

Thanks to the Ann Collins’s skillful editing, the film seamlessly interweaves the cinéma vérité footage of LeBlanc’s students struggling to master a new dance language in the restaging of the piece between interviews with the original company members, archival clips of their 1989 performance, and acclaimed documentary cinematographer Hurwitz’s (Pavarotti) exhilarating shots of present-day Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company performers swimming, sliding, leaping, and diving into outstretched arms (a lot of trust there!).

“Arnie and I were a couple. We were a continent of two on a great adventure,” says Jones, recalling their early years in 1980s New York. “We didn’t want to be part of a racial ghetto. We didn’t want to be part of an arts ghetto, and we didn’t want to be part of a gay ghetto.” With their dance company, the two men began to create a community that had a mission and a direction. “The work was play, the play was work,” remembers original company member Seán Curran. But that community spirit changed rapidly when AIDS struck down Zane, who died in 1988 at age 39.

In the wake of Zane’s death, there was great anxiety among the dancers about whether Jones would go solo. But when he asked them to improvise to a piece of music, to share how they would enter a body of water, there was a sense of relief that the company would continue. In the process of creating D-Man in the Waters, the troupe also found a healing, cathartic ritual that sustained them. “We were hurting,” says Jones, “Work was a way to keep going.”

Adding to the urgency of the new piece was the AIDS illness of dancer Demian Acquavella, whose fighting spirit was celebrated in Jones’s choreography. Although “D-Man,” as the company affectionately nicknamed him, was deathly ill at the time of the ballet’s premiere, a touching clip shows Jones tenderly carrying Acquavella across the stage.

Perhaps the most moving moment in this affecting film is when LeBlanc is brought close to tears at her students’ inability to connect emotionally with Jones’s piece. Born more than a decade after its premiere, they can do the steps and gestures but cannot relate to the trauma out of which D-Man was created. To them, the AIDS crisis is a remote historical event. “Why are we doing this? What are we desperate for?” she asks her young dancers. “What is happening now that is going to make this piece more important than anything else you do?” In rehearsal, Jones urges them to be brave, to be bad motherfuckers, to “bring it.” (A closing end title lists the 26 schools and companies that have performed Jones’s masterwork since it was released for licensing in 2010.)

For dance and documentary lovers, a remarkable and insightful experience.

Leave A Comment