Finding Fela started out as the making-of the Tony-winning Broadway show Fela!, before journeying with the American production’s tour to superstar Fela Kuti’s home base in Lagos, Nigeria. With the discovery of rare performance outtakes and archival footage, plus the willingness of family and friends to talk honestly about the singer/songwriter’s revolutionary life on and off stage, director Alex Gibney turned the project into an entertaining and musically and politically informative portrait of a man, an African, and world music icon.

Twelve years after Fela’s death in 1997, the creation of the musical Fela! provided the entrée for most American audiences. Director/choreographer Bill. T. Jones led the cast through two years of rehearsals and understanding of Fela’s life and music (and hip-shaking dance moves). This documentary records for posterity the astounding Tony-nominated Sahr Ngaujah as the embodiment of Fela (he has gone on to front his own tribute band, Chop and Quench), accompanied by the Brooklyn band Antibalas whose rhythms were inspired by Fela. The numbers here were filmed at a Lagos theater, which re-created Fela’s nightclub headquarters, the Shrine.

Throughout, Gibney provides useful historical, political, and musical visual context about Nigeria before its independence in 1960 through to the corruption and failure of the post-colonial government. Fela’s early life may be a surprise to many, not only because his parents were renowned educational leaders against colonialism, particularly his mother, a preeminent women’s rights activist. He sang in a religious school choir before he went off to London to study classical music at a conservatory. His 1958 report card was found, with poor grades because he was distracted by the jazz clubs. There he discovered the likes of Miles Davis and became a multi-instrumentalist.

He came back home in 1963, and there’s a wonderful tour of the popular highlife scene that fused traditional Ghanaian music with jazz. Key for Fela forming his first band was meeting up with jazz drummer Tony Allen, who is extensively interviewed. (He was cheered enthusiastically as a legend in his own right when he premiered “Red Hot + Fela Live” at Lincoln Center last summer.) Michael Veal, author of Fela: The Life and Times of an African Musical Icon, breaks down Allen’s rhythmic contributions to how he and Fela combined funk, jazz, salsa, Calypso, and traditional Nigerian Yorùbá music into a new Afrobeat.

The powerful influence American black culture exerted on Africa was felt personally for Fela. Beautiful singer and former Black Panther Sandra Izsadore is one of the most colorful Fela intimates interviewed. Still sporting a large Afro and tribal make-up, she describes turning Fela on to both James Brown and Malcolm X: “You can’t just sing about your soup anymore.”

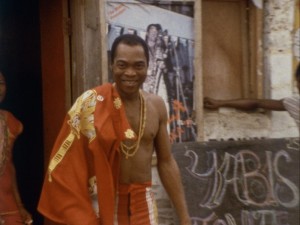

Weekends at the Shrine are relived with exciting rare footage of Fela stirring up his audience. On Friday nights, he sermonized on political issues, formulating ideas that would be worked into lengthy songs for the Saturday night performances (the soundtrack features shortened versions). Fela’s anthemic “Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense” reverberated against corruption in a country where drivers had to pay off traffic cops armed with ready whips. When he sang, “I beg everyone to join my song,” it was more for a political movement than a sing-a-long.

Graphic artist Lemi Ghariokwu shows how Fela’s message became increasingly political through dozens of album covers and concert posters. Fela’s 1977 monster hit “Zombie” mocked goose-stepping marching of authoritarian regimes around the world, and led to his arrest and beating, among the hundreds of imprisonments, and worse: the murder of his mother in a violent raid, which was the emotional climax in the stage show.

At a time when Nigeria was embroiled in civil war, he declared his downtown commune (near an army barracks) the separate Kalakuta Republic. His sex and drug-fueled alternative lifestyle was much more politically destabilizing than the flamboyance of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Mansion or the Ken Kesey in Gibney’s Magic Trip (2011). Izsadore recalls her shock at arriving at her ancestral Africa in 1970– “happy and in love with my man”–only to discover Fela was married, several times over, and expected her to be part of a harem. His exaggerated celebration of free love and polygamy culminated in 1978 when he married 27 women on the scale of King Solomon and called them “his queens.” (His children’s memories of growing up in this environment are quite amusing.)

Not only does the film not shy from his tradition-based misogyny (“Women must know their place”), Gibney is clear-eyed about his subject, as he was last year with Julian Assange and Lance Armstrong. He extends beyond from where Jones ends the stage production when Fela reaches global success. (Sir Paul McCartney thrills at crossing paths.) Gibney moves onward to when the musician fell prey to a fake guru, who Allen ridicules in detail.

The film also faces up to Fela’s death from AIDS (at age 58) and how his lifestyle and denials were part of his problem. Beyond reminisces of his funeral, an outstanding find (in a closet in Italy) are the scenes of the crowds slowly gathering to fill a stadium and then the streets of Lagos as they followed his coffin back to his home. Fela preached “Music is the weapon” and the celebration of his influence continues through the credits as his son Fema Kuti performs with the cast.

I didn’t witness Fela’s reign as the one time biggest musician in Nigeria. I wasn’t born during his reign, but listening to his songs now makes me wish I was. I enjoy listening to his music and wished he was given prestigious awards and recognized more for his awesome work. The article has really gotten my interest. I am going to bookmark your blog and keep checking for new details every week.

Open this link to reach my website and check out its contents. Please let me know if this okay with you. Many Thanks!