This highly informative, empathic documentary centers on the titular black activist, lawyer, poet, author, Episcopal priest, and more, who despite having an outsized impact on modern American life, remains largely unknown. How much so? Murray’s own grandniece, who served as the executor of Murray’s estate, admits having known little about her relative beforehand. In her lifetime, Murray used the pronouns “she”/“her,” but contemporary scholars interviewed here believe Murray, if alive today, would have used “they”/“them,” and these are the pronouns used in this review.

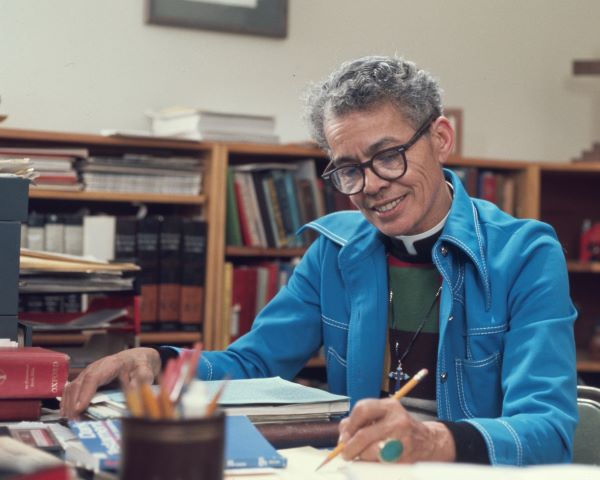

Directors Betsy West and Julie Cohen, along with a cross section of interviewees who lives were touched by Murray’s in some way, attempt to rectify the lack of recognition. Early on, the middle-aged Murray, born Anna Pauline in 1910, looks like a starched-shirt intellectual based on their glasses and eloquent way of speaking. However, the film quickly establishes they meant business, recounting their 1940 arrest for defying Jim Crow laws during a bus ride in Virginia.

The incident resembles the more famous one involving Rosa Parks in Alabama, except Murray’s occurred 15 years earlier. A recurring theme is that the main subject was ahead of their time when it came to ideas of race, gender, and fighting discrimination. The narrative retraces Murray’s life in chronological order to determine how they became a radical, zeroing in on the sense of “otherness” they felt all their life.

That feeling was cultivated through a number of sources, including growing up as a mixed-race child in the South, meaning there was prejudice from both sides of the color line. Murray was also increasingly drawn to dressing up in male clothes and had a burgeoning intellect that set them apart from other school kids.

But we also get a sense of the pain they felt, which feels especially raw at times, thanks to the direct access to their feelings via their own words, samples of which appear constantly. The first half follows Murray’s coming of age, which has both euphoric highs and crushing lows. Although one of the few female students attending Howard University’s law school, they experienced what they deemed “Jane Crow,” discrimination based on gender. Similarly, they recognize their homosexual feelings, but the initial object of their affection rejects them.

Some of the most wrenching scenes involve revisiting Murray’s notes to leading psychiatrists, whom they approached to see if any of them could properly diagnose Murray’s condition. (As some of the scholars interviewed point out, the term “transgender” did not yet exist for Murray.) The contents of these letters range from inquiring about procedures that sound drastic—at one point, they pursue surgery to find undescended testicles—to succumbing to self-loathing, calling themselves a mistake of God.

Yet for all Murray endured, it makes the latter half that much more satisfying as the times start to catch up. This is definitely true for their legal work and activism; especially noteworthy was their argument that “separate, but equal” was unconstitutional, which was initially scoffed at when Murray wrote the argument for their senior thesis. However, the professor who rejected the argument later served on Thurgood Marshall’s legal team for Brown v. Board of Education, whereupon he recalled it.

In the context of the film, it makes perfect sense that Murray would be the one to come up with that then-radical idea. Who else but Murray, who spent so much time as the “other,” would understand the negative psychological effects of separateness?

Murray, who died in 1985, receives posthumous praise from lawyers, activists, and even the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg for taking down “separate, but equal,” as it helped set a precedent for targeting discrimination against women, LGBTQ+ persons, and others. In addition, there are title cards constantly reminding us that Marshall, Ginsburg, and others considered to be trailblazers didn’t break new ground so much as tread where Murray had already stood.

West and Cohen make terrific use of the extensive archive of Murray’s writings and audio recordings at Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library. While it’s one thing to see the subject’s on-screen words, it’s another entirely to hear them. Indeed, there are times in which Murray seems to be an active participant in telling their story. Through the plethora of source material, we see different sides of someone with a masterful control of language and no shortage of empathy. Even in their poem “To the Oppressors,” which gets recited in its entirety, there is less rage than pity toward racists.

My Name Is Pauli Murray is comprehensive enough to be the last word on this notable figure. A shame, however, that for many it will also be the first word.

Leave A Comment