![]() Morgan Neville’s wistful documentary focuses primarily on the ideas that propelled the work of Fred Rogers (1928–2003). Though Neville looks back at Rogers’s TV series, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, which ran from 1968 and ended production in 2000, the film tacitly and poignantly reveals the deficits in today’s fraught cultural climate, namely what is missing in public discourse.

Morgan Neville’s wistful documentary focuses primarily on the ideas that propelled the work of Fred Rogers (1928–2003). Though Neville looks back at Rogers’s TV series, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, which ran from 1968 and ended production in 2000, the film tacitly and poignantly reveals the deficits in today’s fraught cultural climate, namely what is missing in public discourse.

The Neighborhood began as a no-frills, low-budget kids show on WQED in Pittsburgh, just as the Public Broadcasting System was emerging. An ordained Presbyterian minister, Rogers turned to the latest technological invention of the time, television, instead of a traditional pulpit to create a community for children and help them navigate the “difficult modulations of life.” As Rev. George Wirth, a lifelong friend of Rogers, explains in the film, “He didn’t wear a collar; he wore a sweater,” and his message was not oratorical and overtly religious in nature; it was beamed “straight to the hearts” of his viewers. The production itself was a shoestring operation and a team effort—the prop master was enlisted at the last minute to play the character of Mr. McFeely (David Newell).

As host, Rogers took his time on camera, in direct contrast to most of children’s fast-paced programming 50 years ago—and even today. The show became one of PBS’s early hits, and as the movie makes clear, the lanky Rogers was a unique star: low-key, utterly sincere, and direct. The production values were so low tech that one friend, Tom Junod, refers to one of Rogers’s TV sidekicks as a dirty sock puppet.

That would be Daniel the Striped Tiger, a character that, according to Rogers’s son John, was his father’s alter ego. It is through Daniel that Rogers, producer and puppeteer, conveyed life lessons, such as that it’s not easy to quiet doubts. As the film points out, Rogers struggled with lifelong uncertainty and anxiety about his abilities. For example, he expressed in a letter his reservations about how effective he would be when PBS asked him to return to the airwaves and deliver a message to children following the 9/11 attacks.

Neville highlights how Rogers’s faith informed the TV show, yet the director refrains from offering a full-fledged biography. There’s little background here on the subject’s affluent upbringing or adolescence, and only a short aside about how he was bullied because of his weight as a child. The focus here centers on the philosophies underlying his work. Maxwell King’s upcoming book, The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers (Sept; Abrams), paints a fuller portrait, especially Rogers’s collaboration with renowned child psychologist Margaret B. McFarland, and emphasizes how Rogers continuously resisted turning his program into a money-making merchandise marketing machine aimed at children.

The movie reflects the cynical mood of 2018 when it delves into the question: Was Fred Rogers genuine? It’s as though the filmmakers have picked up viewers’ suspicions that there must be a deep, dark secret behind the genial, aw-shucks TV personality. From all accounts, he was the real deal. Even son John says that living with Rogers was like having the “second Christ as your dad.”

Though the tone is respectful throughout, Neville hasn’t made a hagiography. There are hints from Rogers’s longtime crew that reveal his struggles with anxiety and possibly compulsive behavior. Musician and singer François Clemmons, who played Officer Clemmons, offers the most complex and contradictory anecdote. Though Rogers advocated acceptance (“I like you just the way you are,” he would croon), he drew a line about having an out-and-about gay cast member in the series. Circa the late 1960s, Clemmons had been seen at a Pittsburgh gay bar, and Rogers flat-out told the musician he couldn’t go back to the bar, in fear of losing sponsorship or, most likely, sparking a controversy that could hurt the program. Yet Rogers became a father figure to Clemmons, as revealed in one of the more poignant moments in which Clemmons explains that Rogers was “the first man to say he loved me. My father never said that. My stepfather never said that.”

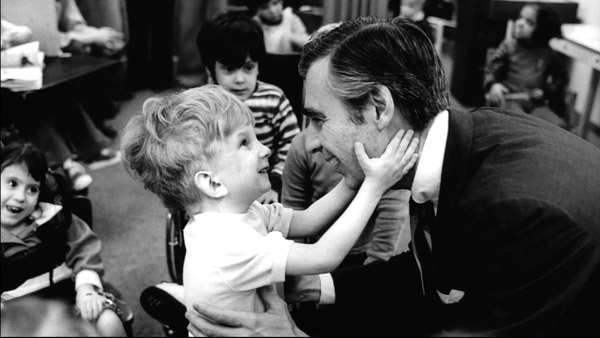

The animated television series Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, which is produced by Fred Rogers Productions, has carried on Rogers’s mission to a new generation. But for adults of a certain age who grew up watching the Neighborhood, the nostalgia of many scenes—especially where Rogers reaches out to children and reassures them that they are special and loved—have a power all their own. The filmmakers structure this profile straightforwardly, but it inevitably becomes a tearjerker, producing a strong emotional response as it becomes apparent that Rogers’s messages bear repeating—and relearning—now more than ever.

This review was first posted on slj.com (June 11, 2018).

Leave A Comment