For their latest film, the Coen brothers change it up a bit and take on the western genre in a series of short films. In doing so, they get a chance to simultaneously zero in on their idiosyncratic style and occasionally depart from it.

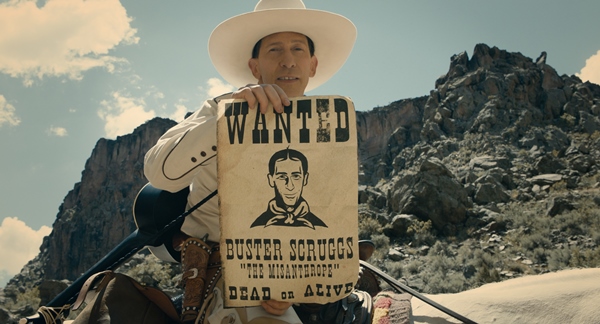

They begin with two very Coen-esque segments: the title story with Tim Blake Nelson as a singing cowboy and deadly gunfighter. This tale has all the signature marks that make you love or hate these guys: folksy narration; cartoon violence; and a cornpone, ironic sentimentality. It’s fun, but very minor stuff, something familiar and digestible, as is the next segment starring James Franco as a hapless and very unlucky bank robber. The visual humor is very much in line with their more quirky fare like Raising Arizona.

And then things get interesting. There’s a grim tale, “Meal Ticket,” about a traveling medicine showman, billed as the impresario (Liam Neeson), whose sole attraction is an armless, legless British young man: Hamilton, the Wingless Thrush, who is a stupendous orator. As the actor recites Shelley, Shakespeare, and the Declaration of Independence, the impresario goes about the crowd picking up cash. When business starts slowing down, you see the need and greed in Neeson’s eyes as his gentle care of the young man turns brusque.

Next is a fun and somewhat sweet, by Coen brothers standards anyway, tale of a ‘49er panning for gold, “All Gold Canyon,” based on a 1904 story by Jack London. It’s ostensibly a straightforward tale about a cheerful and jovial miner (a gloriously crusty Tom Waits) panning for, finding and eventually defending gold. The story opens on a pristinely beautiful valley with butterflies cavorting, eagles soaring, and an elk prancing toward the river. We then hear a gravelly voice singing and a bearded prospector breaking through the tall grass, and suddenly the butterflies and elk disappear. They won’t reappear until the prospector leaves, an obvious way to point out the harm we do to the environment, but the Coens give the tale a playfully cynical zest, so it doesn’t come off as preaching.

For the rest of the segment, we simply watch Waits prospect, which is delightful. He chats with everything around him, including an owl, whose eggs he steals (he takes all of them and then sees the owl staring at him, so he guiltily puts all but one back). It’s a well-placed reprieved as it is sandwiched between the darkest and the deepest segments.

Then comes the piece de resistance. “The Girl That Got Rattled” based on a 1901 short story by Stewart Edward White, traces the (mis)fortunes of a nervous young maiden who, along with her brother, takes part in a wagon train heading west to Oregon, where there is the possibility, according to her older brother, of a marriage. When the brother dies, she falls under the watchful eye of the youngish Billy Knapp (Bill Heck) and the wizened, experienced Mr. Arthur (Grainger Hines). What follows is probably the most heartfelt of any Coen movie I’ve ever seen. For this sequence, they jettison their ironic distance (which I adore) and tell a deeply affecting story without relinquishing their generally pessimist viewpoint. In doing so, they align with a more humanist bent than they have in a past. In a sense, they tell the tale straight and trust in their skills as filmmakers and storytellers, and it succeeds brilliantly.

The final sequence is a little gothic horror bon mot about five folks in a carriage that are being taken ostensibly to a frontier town in Oregon, but metaphorically they arrive someplace else completely. It is reminiscent of tales from Nathaniel Hawthorne or Guy de Maupassant.

These stories are ostensibly based on a book. The wraparound sequence is a man turning the pages of a collection of western stories, and when he lands on an illustrated plate, the following story begins. Aside from the title sequence, clearly a take on the singing cowboy, the other stories’ roots seem to be in short story literature rather than western movies. Mind you, the visual language absolutely takes its cues from Hawks, Ford, and Leone, but the material itself lends itself more to the above mentioned Hawthorne, de Maupassant, as well as Jack London and O. Henry. This, along with the Coen’s signature style, gives the entire film a very different feel than most contemporary homages and nods to the genre.

Of course, the acting is superb. Tom Waits is a hoot as the prospector, and Harry Melling is nothing short of astonishing as the armless, legless performer. Apart from his oratory, Hamilton is silent but keenly observant of any change in the impresario’s behavior, as this character facilitates his survival. Zoe Kazan delivers one of her finest performances as the young, naive woman negotiating her survival on a wagon trail. If she is not up for best supporting actress, I’ll eat my saddle.

All in all, it’s a solid Coen outing with some exceptional moments and their most mature 30 minutes sandwiched in there. Though it is streaming on Netflix, I recommend that you see it in a theater, if only to take in the glory of Bruno Delbonnel’s cinematography, which pays homage to the imagery of westerns past while staying true to the Coens’ hyper-stylization.

Leave A Comment