Through director Michele Josue’s choice to use the casual, familiar moniker of “Matt” in her documentary’s title, she indicates her intent to reveal a personal, untold side of the young man that, for profoundly tragic reasons, we have all come to know as Matthew Shepard.

The diminutive college student from Wyoming, whose name has become synonymous with gay-bashing and hate crimes, was savagely beaten and left to die, tied to a fence in the middle of the prairie, for the simple fact that he was gay. But we already know this part of the story. We’ve seen The Laramie Project, we’ve watched the 20/20 specials. What more is there to reveal about the 21-year-old man whose life was stolen from him, and who has since spurred international headlines, galvanized an open dialogue about hate crimes, and inspired legislation to prevent similar cruelties from occurring?

Attitudes like these suggest that it’s time to take another look at the man many know of only as Matthew the Martyr. Through her film, Josue allows us the chance to do so, but from an unvarnished, intimate, heart-rending new perspective.

Josue and Shepard were teenaged friends attending the American School in Switzerland (TASIS), and they maintained contact for the rest of his young life. The director permeates the film with personal anecdotes, interviews with other companions, and readings of letters and diary entries from Shepard’s left-behinds. This approach would seem invasive had it been executed by an otherwise unconnected filmmaker. With Josue’s careful, embracing touch, it only feels like she’s inviting us to share in her grief and therapeutic soul-searching. She knew Matt—not Matthew—and through the production of this film, she attempts, among other things, to seek some sort of closure.

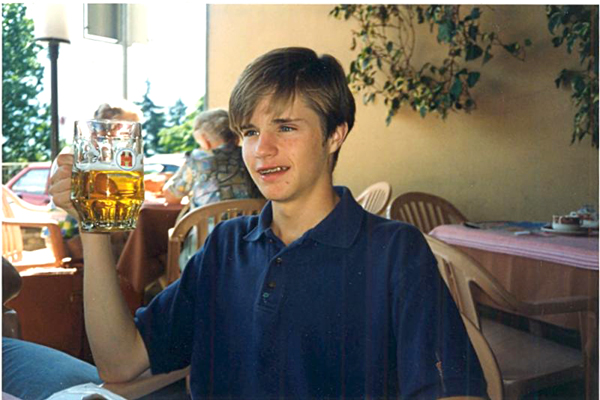

Interviews and voice-overs reference the effect Matt had upon his friends and family. One companion conveys that “Matt always looked into your eyes. Every person had something special about them, and he’d find it and bring it out of them.” Interspersed home movie footage provides additional, cursory moments of relief. Scenes from Shepard family vacations are incorporated alongside daily interactions. One clip of Matt’s younger sibling, Logan, idolizing his older brother from behind the camera, is simultaneously lighthearted and enormously shattering, particularly with the knowledge that in the 16 years since Matt’s death, Logan is still too dismayed to agree to appear in the film.

Josue does not hold back. Through interviews with Shepard’s parents—unbelievably brave and inconceivably forgiving—as well as with former teachers, counselors, and friends, we begin to see Matt as a real, flawed human, rather than as an icon for LGBT rights. Additionally, Josue reveals an assault that was inflicted upon Matt when he traveled to Morocco on a high school trip, and the residual damage that impacted his self-worth.

Shepard was murdered in 1998. At that time, Clinton was president and Ellen DeGeneres had only recently come out on the cover of TIME. Much progress has been made for and by the LGBT community in the intervening years, and a lot of that progress has been catalyzed by Shepard’s murder. As his mother, Judy Shepard, notes toward the film’s conclusion, “I think one of Matt’s greatest legacies is a generation of advocates.” Thanks to Josue’s searing, heartbreaking film, we find another reason to keep fighting for equality: not because we are motivated by martyrdom, but because we should advocate for the sake of humanity, flaws and all.

Leave A Comment