Peter Matthiessen’s 1978 novel The Snow Leopard recounts his journey through the Himalayas with a team of Sherpas as guides. Among them was Tukten, for whom Matthiessen felt a particular reverence, often referring to him as a “shaman” for an unnamable, soulful quality, despite a tendency toward unreliability and pesky behavior. Tukten teaches one of the most valuable lessons of that book about whether a person can ever be fully understood.

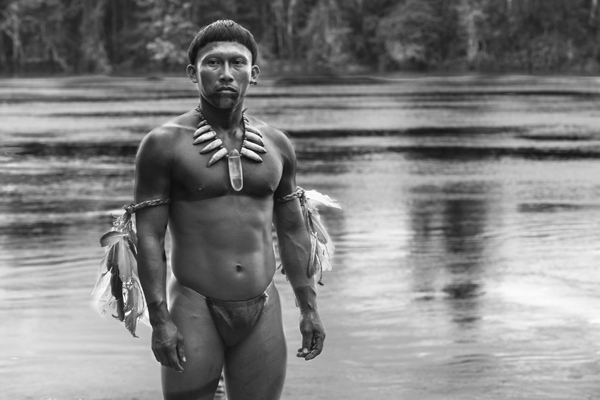

One can see a corollary between Tukten and Karamakate, our Amazonian guide in Colombian director Ciro Guerra’s Academy Award-nominated Embrace of the Serpent. The last of a subsumed tribe in a Colombian controlled region of the jungle in the early 20th century, Karamakate provides aid to two generations of white scientist-explorers. Based on actual people, and intercut between two storylines decades apart, German-born Theo (the elder) and American-born Evan (the younger) search for a rare plant called the yakruna, and coincidentally both meet Karamakate. Theo is attempting to cure himself of a jungle disease, while Evan is interested in a property of the yakruna that increases the purity of rubber—a major cash crop of the region.

The younger Karamakate, who encounters Theo, is a passionate and impulsive man, capable of great wisdom, yet he often acts on instinct. Decades later, the elder has mellowed significantly, even believing he has become a chullachaqui, a hollow version of himself possessing neither memory nor soul. As the older Karamakate continues down the river with Evan and encounters reminders of his previous journey, years prior, it is revealed that his memory is still very much intact. Whether he’s jogged by the past or just conveniently withholding information from the opportunistic white man, the answer is never quite provided. The earlier journey with Theo, though, reveals a wealth of story details to fill in the character and motivations of the older Karamakate.

What emerges strongest in this fresh and remarkable film is a discussion on belief and its roots. Theo is ostensibly a more conscientious and pure observer than his would-be successor. (They never meet, though Evan relies heavily on Theo’s diaries.) But Theo is not without his failings. A mix-up over a compass he offers to a local tribe leads to a fascinating meditation on the different meanings this object takes on, depending on who is the observer. An altercation at a Spanish monastery, including an update on its status decades later, provides yet another insight on the yearning for answers in religion. Karamakate remains opaque throughout, yet by the end he still imparts a powerful lesson. Perhaps, watching this man, the last of his kind, as he exports his indigenous wisdom through the evangelizing writings of the white scientists-turned-ethnographers, we see that belief is a tool of self-preservation. Make others believe what we do and our way of life continues.

Yet what does he believe? Though the episodic details of these parallel odysseys converge through the character of Karamakate, he still somehow remains like Tukten, the shaman who cannot be grasped—even by us, an audience with front row seats. Our Western way of understanding is clearly different somehow. And it is through storytelling that we can begin to make a connection with someone who does not possess the same words or concepts. If you’re the type that likes the experience of understanding without fully grasping, here’s your movie. If you’d like to be taught something inexpressible, please meet Karamakate.

Leave A Comment