When artists reach their peak too soon, they can become instant legends. Conversely, the first stroke of genius in a masterful debut might mean a curse regarding future work. There probably isn’t a better example in cinema history than Orson Welles and Citizen Kane (1941), a first feature that’s arguably one of the best films of all time. Nothing that Welles made later achieved the same level of recognition (and there were great stuff and fascinating experiments along the way). Worse than that, his projects faced too many problems, from mutilated final cuts not approved by him to incompleted movies. Dennis Hopper, an actor turned director, had a similar experience after creating a generation-defining film. Easy Rider (1969) probably isn’t an indisputable masterpiece as Citizen Kane, but it’s hard to deny its importance as a pinnacle of change in American cinema.

What if you could imagine a scenario in which Welles and Hopper shared a long conversation about their lives and work? Luckily, no one has to invent it. The encounter was filmed on Welles’s command in 1970 while immersed in the completion of The Other Side of the Wind, a film that would never see the light of the day when the director was alive. It was finally completed in 2018. The same team that assembled and brought back to life that lost gem in Welles filmography (Filip Jan Rymsza as a producer, Bob Murawski as editor) joined forces again to rescue this material of a heady two-hour discussion between two titans.

It is an intense and—to a certain point—confrontational interview that works as an essential documentary about filmmaking. Hopper was working on The Last Movie (1971) when this was recorded and enjoying fame post-Easy Rider and absolute creative freedom for his sophomore feature. The complicated production of that particular film, with a title that was more than prophetic, would end in commercial and critical failure. While he sustained a prolific career as an actor, he did not have as many subsequent incursions as a director after The Last Movie, which has garnered reappraisal and cult status over the years. So the meeting with Welles happened at a crucial moment for both. One of them was planning a comeback (unsuccessfully), the other was just months away before a critical fall from grace. For viewers well aware of how the future went, watching these two artists in Hopper/Welles is a mesmerizing experience.

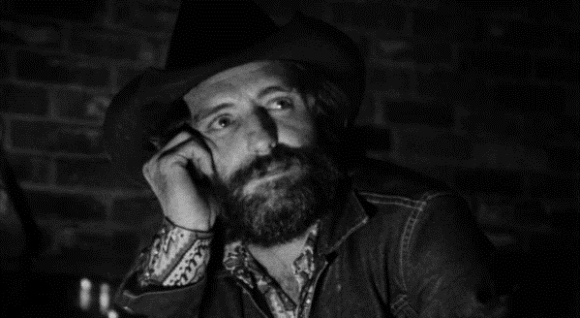

The film functions as an in-the-moment documentary. The mise-en-scène is claustrophobic, mostly centered on Hopper’s obscured face: a young, handsome, occasionally shy guy who can’t stop messing with his beard. Some others are in the room, but they barely intervene over the exhausting back-and-forth between the filmmakers. Of course, Welles dominates over his guest (a material that was supposed to be part of The Other Side of the Wind, after all), yet he never appears on-screen. We only hear his cavernous, unmistakable voice proposing topics, insisting on unanswered questions, and pushing Hopper’s limits as much as possible to the edge of his worst contradictions.

Welles acts like a god, establishing a Socratic dialogue to find some truth in Hopper’s half-baked affirmations and naive idealism. Hopper was then a symbol of a younger generation anxious to create a different world and new approaches to art. In the process, Welles obliges Hopper to cover various subjects, such as the nature of the director as a magician or god (Hopper can’t find a clear difference), the futility—or not?—of political activism (“I’m not Jane Fonda,” says Hopper, confirming later that he expects to change the world with his movies), and their rich impressions on other films and their directors. (There’s a funny disagreement in classifying Buñuel as a Catholic or a communist).

On a personal level, Hopper confesses about his complicated relationship with a castrating mother and an indifferent father. On many occasions, Hopper insists children should grow up hating their fathers: they can’t bring change to the world otherwise. He also states he makes movies to reveal the mistakes parents (those he condemns as “the John Wayne generation”) have committed.

There’s a big contrast between an older man confident in his arrogance, with no shame, debating a younger counterpart who’s afraid to reveal his monstrous vanity, but his self-deprecatory ego (“I’m not an intellectual,” “I don’t read books”) hides shades of pretension even greater than what Welles manifests. Welles doesn’t allow him not to answer, requiring clear answers on how Hopper will change things if he fears expressing any political opinion.

The best moments are reserved for when the opposite personalities speak directly about cinema. Hopper says that after making a film, he understands better the effort to make it. He appreciates every movie just for its sole existence. This interchange—and film—will bring joy for those who admire movies and those trying to change the world through cinematic tricks. They usually fail, except, as Welles would say, Jane Fonda.

Leave A Comment