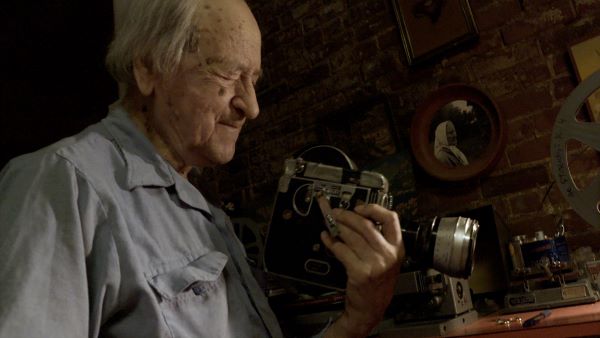

Alan Hofmanis, left with boom mic, and Isaac Nabwana, with camera, in Once Upon a Time in Uganda (DOC NYC)

What is touted as the largest documentary film festival in the United States returns to New York City, and in theaters for the first time since the pandemic. Running from November 10-18, DOC NYC screens some 120 feature documentaries and 80 shorts. Most importantly, the festival has continued with an adjustment it made last year. It will continue to offer the bulk of its programming online for U.S. viewers from November 19-28. Though not every title will be added to the online platform, a large number of some of the best films in the festival (and of the year) will be streaming, such as Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s Flee and Todd Haynes’s The Velvet Underground.

The range of choices is overwhelming. Where to begin? Just selecting by subject yields numerous options, such as in the “Fight the Power” category, which includes the timely Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America and The Gig Is Up, so the films below represent only a piece of the programming, here loosely centered around film history and filmmakers. These movies will be available on the DOC NYC streaming portal, and all are recommended. They are examples of the wide range of the festival.

Once Upon a Time in Uganda

It is particularly fitting that Once Upon a Time in Uganda has its U.S. premiere at DOC NYC; one question it raises is, what is the purpose of festivals? What films are considered worthy and by whom? For festivals that have the wherewithal to cast a wide net and celebrate all types of filmmaking, the unabashedly lowbrow action comedies of Uganda director Isaac Nabwana are catnip. Cathryne Czubek’s engaging account of his discovery by the international press and the festival circuit should be an inspiration to budding filmmakers.

The documentary and Nabwana push back on preconceived notions of what subject matter a work from East Africa should be about. Movies about poverty, war, and internal strife already circulate on the international film circuit, and most of them are European co-productions, often made in Francophone countries. Nabwana, on the other hand, just wants to entertain.

Living in the district of Wakaliga in the capital city of Kampala, the former brick maker is a self-taught DIY creator. Filmed with a budget of around $200, using in-camera special effects and unpaid volunteers, his gleefully anarchic movies feature more exploding heads per minute than likely any other director, with titles like Who Killed Captain Alex? and Eaten Alive in Uganda. He’s the chief purveyor of the beating-up-the-White-person genre, and his inspirations are usually not considered part of the film school canon: Chuck Norris, Bruce Lee, and the Italian actor Bud Spencer. His movies are screened accompanied by a VJ, a video jockey who offers commentary much in the way of the snarky commentators of Mystery Science Theater 3000. As his wife, Harriet, explains, in Uganda, “cinema is for the rich.” Her husband’s films, on the other hand, are for the “ghetto” (her description). Don’t expect them to be in competition at Venice or Cannes anytime soon.

Two weeks after Alan Hofmanis broke up with his girlfriend, he left New York City and landed in Uganda. A man of all trades—a publicist and a film programmer—Hofmanis became intrigued by a trailer he saw on YouTube of one of Nabwana’s films. The New Yorker moved in near the Nabwana family and became a collaborator, along with Harriet and a community of all ages, where he found “joy and creativity.” His timing was fortuitous: the director desperately needed a Muzungu (White man) for his next project.

Presumably through his press connections, Hofmanis works to bring the spotlight to Nabwana. He has succeeded: you may have heard of “Wakaliwood” via Vice, CNN, and the Wall Street Journal, to name a few outlets. Yet, like many independent filmmakers, the lack of money becomes an ongoing issue, and Nabwana seeks out a deal with a television network, causing Hofmanis to feel left out in the cold. The partnership erupts, to Alan’s regret: “We could have been the Beatles of exploding heads.” However, there is something of a Hollywood ending.

Nabwana’s rambunctious filmmaking is a hoot, proof that not every film has to have a Profound Message.

Film, the Living Record of Our Memory

Film nerds, rejoice! One of this year’s gems is on a mission aligned with most large film festivals. Film, the Living Record of Our Memory gives motion picture historians, restorers, and archivists their due and a place in the sun. Besides preserving decaying film before it disintegrates, and tracking down lost movies, archivists have broadened the perception and the scope of the accepted film canon through the discovery of lost treasures throughout the world. Despite its academic title, this selection is an effortlessly enjoyable treat for cinephiles.

Much of film history has already been lost. It is estimated that 80 percent of silent films are gone forever. Nitrate film, which was in use until 1950, was often melted down for silver after a movie’s theatrical run. Or, studios dumped footage into the Pacific Ocean, thinking these films no longer had commercial value. (Say what you will about Walt Disney, but he was a forerunner in film preservation. Of course, he realized that there was a new audience for his films within every decade.)

For restorers, preservation too often involves the difficult decision of what can be saved. In many countries, the humidity and the lack of funding pose formidable challenges, making restoration of existing work a luxury. Cringe warning: there are numerous shots of brown, round mounds of dust of what were once reels of film.

Most of the early archives were founded by collectors, and we have Henri Langlois, co-founder of the Cinémathèque Française, to thank for saving Murnau’s Faust (1926) and Nosferatu (1922) from the Nazis in the early 1940s. (For more on Langlois and his place in French film culture, the 2004 documentary Henri Langlois: Phantom of the Cinémathèque is available on Kanopy.) In just one example of how film preservation is a collaborative effort, a lot of German films were found in Moscow after having been taken there as spoils of World War II. Likewise, films that Nazi Germany had confiscated from countries it occupied also wound up in the Soviet Union.

The film widens its scope to include archivists throughout the world and to look beyond the history of narrative films. Director Inés Toharia takes an expensive view; it’s by no means centered on Hollywood’s Golden Age. Home movies have remarkable historical value, such as those that captured life in a Japanese internment camp in California and in post-Kristallnacht Vienna.

There will bound to be new discoveries here for the most hardened film buff, such as Pan si Dong (The Cave of the Silken Web), a 1927 film based on an episode from Journey to the West—seven of its 10 reels were rediscovered in a Norwegian national library—and the work of pioneering Tunisian photographer/filmmaker Albert Samama Chikli. The film also raises the thorny question of how digitally-created content will be maintained. For now, the most reliable way to maintain visual material is by way of an older technology: 35mm film.

This is a must-see for TCM addicts, Criterion Channel subscribers, and other film buffs. If it preaches to the choir, it’s still a powerful sermon.

Fittingly, Toharia allows the late avant-garde filmmaker/archivist Jonas Mekas to have the last word, “if you love something, you have to do everything to preserve it.”

The Real Charlie Chaplin

As if to highlight the startling results of film preservation, The Real Charlie Chaplin underscores its benefits through the abundant, still hilarious, and visually crisp clips of the groundbreaking comedian and filmmaker. The crystal clear, cleaned up audio recordings of Chaplin and those in his orbit especially stand out. They include Virginia Cherrill, his costar in 1931’s City Lights, who lightly shuts down the rumor that she had a relationship with Chaplin (“I was too old.” She was 20.), and three of his children with his fourth wife, Oona O’Neill, including actress Geraldine Chaplin.

The documentary’s directors, Peter Middleton and James Spinney, reenact film historian Kevin Brownlow’s early 1980’s kitchen sit-down with Chaplin’s spry and frank childhood neighbor Effie Wisdom, who was over 90 at the time, using the original audio recording. (The real Brownlow features prominently in Film, the Living Record of Our Memory; he’s this year’s DOC NYC MVP.) The most revelatory sound clip, the ruckus 1947 press conference for Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux, turns into a verbal scrimmage with the press, over his political beliefs.

For those familiar with the artist’s biography, this is a speed-through and a somewhat choppy account of his event-filled life, with British actress Pearl Mackie standing in as the narrator. It begins with the origins of his character, the Tramp or the Little Man, and mentions a legal suit he brought in the 1920s against a “Charlie Aplin” for copying his onscreen persona. In the trial, two of Chaplin’s former vaudevillian troop mates testified that they had created the world-famous character. Strangely, the film never mentions the outcome or the ruling of the case. (The Superior Court of the State of California ruled in Chaplin’s favor.) Based on his biography and an interview here, Chaplin found the character by experimentation. He borrowed a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

At only two hours, the biodoc omits his relationship with silent film star and collaborator Edna Purviance, briefly mentions Paulette Goddard (his costar in two of his greatest films and his third wife), and downplays his mother’s role in his life. The most egregious omission for this viewer: there is no retelling of the amazing tightrope walking scene from The Circus. His life story is more suitable for a multi-episode series. However, as an example of his filmmaking, the documentary recounts the long filming schedule for City Lights—he created the story line as he went along without a script. It took him more than a year to have a eureka moment, to figure out the film’s pivotal moment. Here, viewers see the equivalent of his many drafts.

With some overlap, this makes for a fitting companion piece to Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange’s 2013 The Birth of the Tramp, which zeroes in on Chaplin’s early years in vaudeville and covers more of the era’s English music hall scene, where he learned the tricks of the physical comedy trade, and how the young actor incorporated his stage acts into his early silent two or three reelers. Kevin Brownlow and Michael Kloft’s 2002 The Tramp and the Dictator goes into more detail over the eerie parallels between Chaplin and Adolf Hitler.

Still, Middleton and Spinney’s film makes for a good introduction for those who have never seen Chaplin’s feature length films; it includes choice moments from his early days of stardom up to The Great Dictator and, briefly, Limelight. Additionally, this is perhaps the most sympathetic accounting of his second wife, Lita Grey, whom he married when she was 16. She was divorced in what was the most expensive Hollywood settlement at the time. The animosity lingered; he doesn’t mention her by name in his 1964 biography. And for those who want to know more about Hedda Hopper and J. Edgar Hoover’s collaboration in brutally taking down Chaplin, listen to the podcast You Must Remember This, episode four of the season: “Gossip Girls: Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper.”

Leave A Comment