In the early 20th century, a new breed of weapons was introduced to the battlefield: poison gas. The chemical weapon is deemed so dangerous and inhumane that it has been banned. In the middle of that century, the most destructive weapon ever devised was used in war, the atomic bomb. Poison gas and the atomic bomb inspired a massive public discussion, influenced by peace movements, and an examination of our values and the kind of world we want to live in.

Filmmaker Alex Gibney’s new film reveals that a new type of weapon, cyber warfare, has already been created and deployed, with barely a hint of public awareness. Gibney fills Zero Days with compelling details, including about the numerous infiltrations of an Iranian nuclear facility by U.S. and Israeli spies, disguised as janitors manually delivering infected flash drives. The film pulls back the curtain on an operation that would put any Mission: Impossible movie to shame.

The documentary takes us through the complex, secretive genesis of the world’s most powerful cyber weapon, starting with its 2012 discovery by Sergey Ulasen, a Belarusian employee of Kaspersky, a leading global antivirus company. His fellow employees, as well as experts in combating malware (malicious software), discuss their continual amazement as they discovered more properties of this strange new malware, which they dubbed Stuxnet. The aspect that made Stuxnet unique was that it had the capacity to target programmable logic computers (PLCs). PLCs form the link between computer networks and infrastructural hardware. Stuxnet could make the leap from networks to real-world chaos, shutting down major infrastructure.

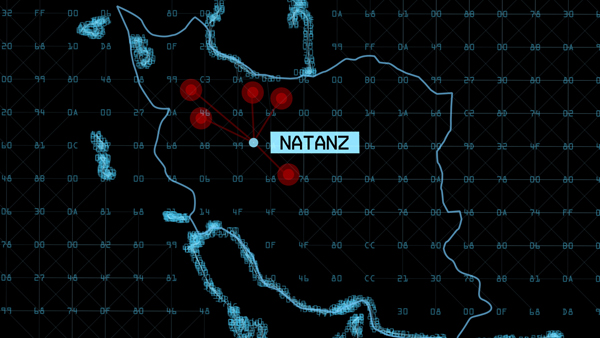

The film then brings us back to 2009-2010, when Stuxnet was operative and doling out its damage. Though officials have never publicly confirmed any of this, whistleblowers have admitted—many of them for the first time here—that Stuxnet was the result of a top-secret, multi-year collaboration between the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency and the Israeli equivalent, Mossad. It was intended to specifically target the foremost uranium enrichment facility in Natanz, Iran. Uranium enrichment is needed for nuclear power but can also be used for nuclear weapons.

Despite Iran’s apparent total compliance with International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA) guidelines and inspections, the United States and Israel refused, and still refuse, to believe that Iran doesn’t have intentions to build nuclear weapons for the express purpose of attacking Israel. These concerns are not entirely without merit, as former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad infamously claimed that Israel was a source of evil in the region and should be wiped off the map and linked the Jewish state with the “satanic” United States. Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has understandably taken that statement at face value as an existential threat against his state, but it’s also possible that Ahmadinejad, now three years out of office, intended his statement as a clumsy critique of the Israeli occupation of Palestine and the U.S.’s role in selling advanced weapons to Israel.

Suspicion reached a fever pitch in the years following 2006, when Netanyahu famously compared Ahmadinejad’s Iran to Hitler’s Germany in 1938, as a sleeping evil being allowed to gather strength by a less than vigilant West. The timing for the creation of Stuxnet was ideal, since in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, many new powerful federal agencies were created, including U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM), a new branch of the military operating in the digital space. While the CIA and the NSA were key players in creating Stuxnet, USCYBERCOM played the most central role, along with Mossad. Like all branches of the U.S. military, both defensive and offensive tools and tactics were devised.

As if all of this weren’t enough, Zero Days takes an extensive tour through the finer points of uranium enrichment centrifuges. To understand what Stuxnet did, one needs to understand how these centrifuges function. These centrifuges at the Natanz facility were the explicit targets of the digital weapon, and they started malfunctioning in 2009, throwing a monkey wrench into their ability to create the nuclear power that the IAEA granted them permission to have.

If we take Iran and the IAEA at their word and believe that they were not secretly building nuclear bombs to use against Israel, then this was an unprovoked, unjustified attack on their critical infrastructure. It is all the more alarming because Stuxnet caused the enrichment centrifuges to spin so fast that they malfunctioned. Does massively increasing the rotational speed of uranium enrichment centrifuges in an enormous nuclear power plant seem like a safe thing to do? What would Americans say if Iran did this to our nuclear facilities?

After the initial and successful deployment, Mossad created a far more aggressive version, designed to be spread around the world and to increase the number of parties to potentially deliver it surreptitiously to the Natanz facility. The infection of American networks became so severe that the Department of Homeland Security spent millions investigating the malware as a potentially lethal threat, totally unaware that the U.S. Cyber Command, the CIA, and the NSA created it.

We have already seen major blowback, as this cyberattack by Israeli and American forces galvanized a generation of young Iranians, motivating them to become world-class cyber warriors. In 2012 and 2013, Iran’s thriving new cyber army hacked Saudi Aramco’s 30,000 computer devices, erasing all its code. Iran also massively disrupted online banking functionality of firms such as Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and more.

Zero Days is an important educational tool to point out to the American public that these attacks were in response to Stuxnet, rather than the kind of belligerent, unprovoked extremism they have largely been interpreted as. A peculiar quirk of American power is an inability to notice that it can actually be in the wrong. Hopefully, Zero Days will remind the viewers just how dangerously wrongheaded power can be, and indeed often is.

Leave A Comment