![]() The murder of Kitty Genovese is one of the most famous cases in the history of sociology and criminology, up there with Phineas Gage and Jack the Ripper. Everyone knows the story. In 1964, a young New York City woman was stabbed to death on the street in full view of her neighbors, scores of whom looked on while she perished. The case has become emblematic of contemporary urban apathy, isolation, and the disintegration of social bonds. But as the documentary The Witness reveals, just about everything we thought we knew about this most well-known of crime stories is wrong.

The murder of Kitty Genovese is one of the most famous cases in the history of sociology and criminology, up there with Phineas Gage and Jack the Ripper. Everyone knows the story. In 1964, a young New York City woman was stabbed to death on the street in full view of her neighbors, scores of whom looked on while she perished. The case has become emblematic of contemporary urban apathy, isolation, and the disintegration of social bonds. But as the documentary The Witness reveals, just about everything we thought we knew about this most well-known of crime stories is wrong.

Shortly after the murder, the New York Times published an article that went unchallenged, largely until this very documentary. The film follows Kitty’s youngest brother, William, pursuing the real facts of the case and finding out that much of the original Times story could not have been accurate. Through painstaking reconstruction and analysis bordering on obsession, William shows that due to the layout of the area where the murder occurred, it wasn’t possible for 38 people to have witnessed the crime, as the Times reported. In addition, while there were many ear witnesses, this was New York City, so most of those who overheard the murder assumed the commotion was an alcohol-fueled lovers’ quarrel or some sort of domestic spat.

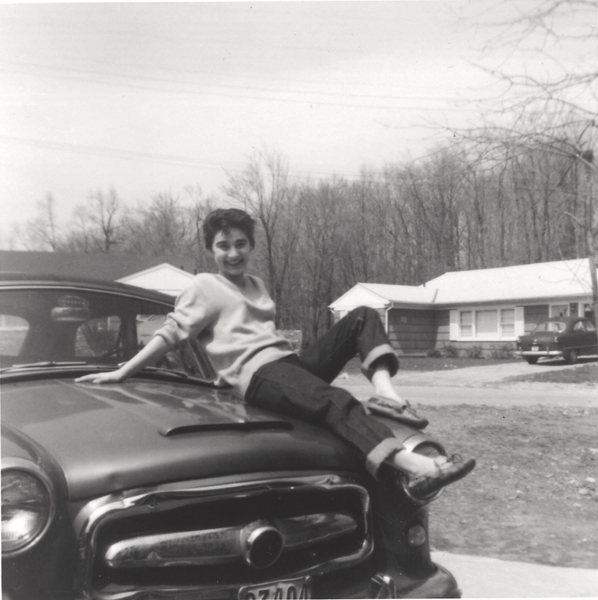

Another of its goals is reintroducing his sister, Kitty Genovese, as an actual person. Largely lost to history, she has been molded into whatever sociologists and criminologists who bandy her name about want her to be. But in truth, she was not a helpless victim. In fact, according to the film, she was in many ways ahead of her time. She married a man named Rocco who her family barely knew, and that marriage ended fast presumably because Kitty was a lesbian. She disobeyed her parents’ pleas to move to the safe suburbs, as she loved the freedom and excitement of New York City, flitting all around in a sleek car. She lived in Queens with her lesbian lover and worked at a nearby bar, over which she presided with Diane Chambers-esque panache. In his quest to bring the real Kitty to light, William sits down with some of her favorite patrons, who recall her kindness and joie de vivre even after 50 years.

Kitty died in 1964, and the country was caught up in grief over the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Between JFK’s death and the engulfing morass of the Vietnam War, the country was ready to validate its own worst fears about the dark specter of moral nihilism. And so Kitty’s story—which led to the idea in social psychology known as the Bystander Effect, wherein parties present at a crime or misfortune do nothing to assist the imperiled party—was perfectly timed.

But as the documentary makes clear, the Bystander Effect narrative was largely false. The real story was that Kitty’s relatively unremarked upon killer, Winston Moseley, was a full-blown homicidal psychopath in the Ted Bundy sense. However, this was 1964, well before the particularly American scourge of psychopathic serial killers gained widespread public attention. That someone could commit that kind of violent act again and again, simply out of pure bloodlust, was simply beyond the pale. (Moseley had already committed one murder, which was as diabolical and depraved as any of the atrocities carried out by the most infamous of late 20th-century serial killers.)

The Witness accomplishes something remarkable by making us reconsider a story, and a concept, that we’ve long taken for granted as true. While Kitty Genovese’s murder, and the cottage industry of sociological speculation it fueled, remain major historical happenings, it is high time we all learned who Kitty really was and what her death was really about.

Leave A Comment