This year, the Tribeca Film Festival gave awards to pointed portraits of political engagement. These documentaries raise thoughtful and tangled issues about how the very personal becomes political.

Point and Shoot

A shy OCD-beset young guy, Matt VanDyke, left his mother’s Baltimore basement and his girlfriend for a North African-to-Middle Eastern odyssey, and plunged into war zones and revolution. He first was inspired to toughen up by the adventure films of Australian Alby Mangels, with visions of Lawrence of Arabia and Ernest Hemingway dancing in his head. The only time his camera wasn’t running was during the six months he was locked up in a Libyan jail.

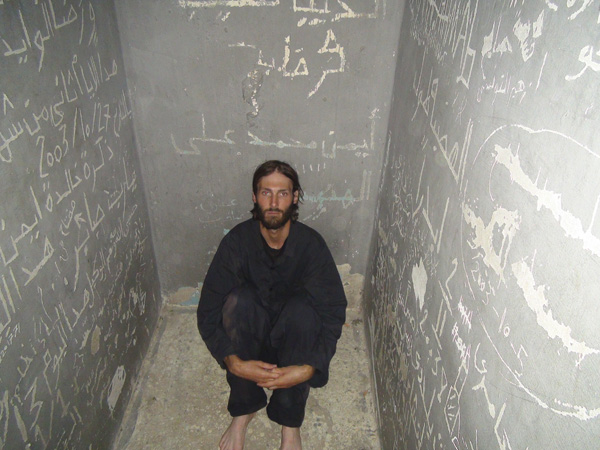

The festival’s best documentary award winner has, in effect, two directors. VanDyke shot hundreds of hours of raw footage over five years from 2006. Then documentarian Marshall Curry culled the mostly selfies (much like Werner Herzog edited a loner’s footage in Grizzly Man in 2005) and organized them around extensive interviews with VanDyke. Thus, he becomes an unchallenged narrator, like another young man ambiguously caught up in questionable political activities in Curry’s If a Tree Falls (2011). His hallucinatory isolation in Qaddafi’s prison cell, shown through effective animation, could just as well be from Midnight Express as from his capture with feckless rebel friends.

By splicing the images inside VanDyke’s head, Curry honestly reveals the lines that VanDyke kept crossing, from motorcycle daredevil, citizen journalist, enabler of preening guys with guns, to gonzo revolutionary. Just when you get exasperated with VanDyke’s narcissism and naiveté, the closing scroll shows that he has matured from this quixotic adventure. He’s now thrown himself into the Syrian civil war, and has made a responsible short film Not Anymore: A Story of Revolution that lets the world meet young opponents of that country’s regime.

Regarding Susan Sontag

Voluminously prolific and opinionated, Susan Sontag appears first on the screen as the very model of the modern public intellectual tilting against the tide of American public opinion after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center. Her visibility extended to movies and TV spoofs, even on The Simpsons. Director Nancy Kates thoroughly explores the several lives of a woman, who was a brilliant prodigy, and her bouts of cancer that killed her in 2004. Like so many of her generation of Depression babies, Sontag kept her complicated and vacillating bicoastal, bicontinental, and bisexual relationships private.

Her sister remembers how Sontag’s private ambivalence started with her Jewish identity in Hollywood when she dropped her father’s name of Rosenblatt to take on her stepfather’s name. Her affairs with domineering, older intellectual men led briefly to her turning into a 1950’s wife and mother. While commentary by biographers and historians view her through a predictable feminist lens, the interviews with her former female lovers in Paris and New York (artists, including dancer Lucinda Childs, and academics) are the most revealing about what she was like on a day-to-day basis. (There is no new interview with her later, more well-known, companion, Annie Leibovitz.)

Winning a special mention from the festival jury for feature documentaries, the film’s like recent biographies of Emma Goldman and Simone de Beauvoir that have exposed the contradictions between a fierce public persona of independence and the emotional compromises of a woman in the throes of passionate and erotic love. This insightful contrast between theory and practice in gender relations will be on HBO in the fall.

Ne Me Quitte Pas

Far away from the public eye, two old friends in the rural woods of Belgium intimately illustrate Thoreau’s description of men leading lives of quiet desperation: “stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind.” They drink. A lot. Awarded Best Documentary Editing, this is the most clear-eyed, unsentimental, discouraging, and fly-on-the-wall verité look at the insidiousness and wallowing of alcoholism as a disease since Lionel Rogosin’s On the Bowery in 1956—but with a surprisingly spry sense of humor.

Marcel, a Walloon who is trying to be a responsible father to his young children, and Bob, a Flemish cowboy and estranged father of an adult son, have a great and loyal time together, even while falling down drunk on the road and as Marcel goes in and out of rehab. As very frustrating as they can be to watch, directors Sabine Lubbe Bakker and Niels van Koevorden in an interview with me noted the men’s hopeless attitudes mirror the region’s years of severe economic depression. This is also a sobering look at the limits of government assistance to help.

1971

A real-life Oceans 11 plays out as a political thriller with eerie timeliness in the exposure of a 40-year-old mystery: how a FBI office outside Philadelphia was robbed of all its files to confirm for the first time government surveillance, infiltration, and disruption of anti-war, feminist, and civil rights groups and the lives of individuals because of their political opinions. Five of the eight suburban activists in the self-styled Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI tell first-time director Johanna Hamilton how they methodically pulled off the theft, leaked the documents, and nervously eluded a massive FBI dragnet, well after the statute of limitations ran out. They kept silent until now.

Recruited by a physics professor, the conspirators, including teachers and a social worker, give first-person, step-by-step accounts of how they formed a tight-knit band to systematically survey a surprisingly soft target. Additionally, they learned the necessary burglary and stake out skills. Key to their success was their clever idea to hit the office on March 8, 1971, when most everybody, including guards at the courthouse across the street, would be distracted by the heavyweight championship bout between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. The shadowy reenactments are suspensefully credible and effective, such as when the sole woman in the group, a mother of three, disguises herself as a college reporter to get inside to case the office. She became J. Edgar Hoover’s number one enemy.

Also interviewed is Washington Post reporter Betty Medsger, the first to publish the purloined documents they sent out to journalists (and the only one not to return them to the FBI). She found out the identities of most of them just a few years ago. Her companion book, The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI, provides more background on the participants’ motivations and lives before and after the robbery (including activities that make the FBI look really incompetent for not matching their involvement in the heist).

Tantalizingly unsolved is the unidentified ninth member who backed out yet was pressured by agents to divulge the plot, leaving the rest in constant fear that a pointed finger would lead to jail. Emphasis is instead put on one memo curiously marked “COINTELPRO,” which led years later to a Freedom of Information request that uncovered the full extent of Hoover’s out-of-control flouting of constitutional rights and spurred reforms that lasted up until the post-9/11 Patriot Act made such close surveillance legal.

The Newburgh Sting

1971 includes a victory for two of the antiwar activists on trial as part of “The Camden 28,” whose case was thrown out by a judge critical of the over-involvement of a duplicitous FBI provocateur. Ironically, times have changed. Now such an informant can be seen in another documentary selectively videotaping himself recruiting, bribing, supplying, and directing poor young black men because they are ostensibly Muslim.

Husband-and-wife documentarians David Heilbroner and Kate Davis only give the defense’s viewpoint, including extensive interviews with the distraught families and the local imam, in tracing how four guys with low-level criminal backgrounds from the slums of upstate New York ended up paraded on TV by smug law enforcement officials and through the courts as thwarted sophisticated bombers. (The local and national media have only covered the government’s side.)

The evidentiary videotapes of the supposed representative of some vague rich foreign group dangling big bucks in front of the incredibly gullible and impressionable men looks like any common sense definition of entrapment. (A late-joiner to the group is borderline development disabled). Legalisms would just reinforce the viewers’ astonishment that this isn’t considered a miscarriage of justice. HBO is broadcasting this film as part of its annual summer documentary series.

Silenced

When is a leak of government secrets illegal espionage or legitimate whistleblowing? Director James Spione delves deeply into the heavy personal and professional cost—emotional and financial—on three of the eight people who have been charged by the Obama administration with violating the Espionage Act of 1917.

Thomas Drake, a former senior National Security official, followed every bureaucratic requirement specified in the 1989 Whistleblowers Protection Act in criticizing illegal surveillance efforts before going to the press. (The terms of those safeguards should have been specified more clearly.) Yet those professional procedures only gave him a Pyrrhic victory after facing down a protracted and expensive lawsuit.

CIA officer John Kiriakou was less careful than many anonymous senior administration officials in talking on the record to the media when he confirmed the use of waterboarding, and it feels like psychological waterboarding when his family is seen being left destitute in battling the government’s espionage charges. His wife read a statement after a Tribeca screening poignantly pleading for support for his legal defense fund.

The film is at its strongest in the verité unfolding of events and weakest in its overly melodramatic reenactments. This is particularly so in looking at the difficulties faced by former Justice Department ethics lawyer Jesselyn Radack. She objected to the legal treatment of “the American Taliban” John Walker Lindh when he was in custody in Afghanistan. While more confusing than the others about her specific actions and the retaliatory reactions, the resulting pressure she endured seems like the bad old blacklisting days. She now specializes in defending (very appreciative) whistleblowers for the Government Accountability Project, including representing Edward Snowden to qualify for such status, and she is a forceful advocate for them here.

The awful violence in Central and South America that is driving minors to migrate to the United States feels just barely fictionalized in the festival’s Best New Narrative Director Award winner. Manos Sucias is The Wire on water, along the dangerous Colombian coast, where risky drug running offers the only employment for young men in poor villages who still have hopes for a better life.

In these mean boats, two estranged brothers, still recovering from the ravages of a continuing war, are hired by a large drug dealing operation to assist a thug smuggle 100 kilos of cocaine not just past the police, but also dodge the navy and the paramilitaries. Chase scenes of jerry-rigged scooters on abandoned railroad tracks are thrilling, yet director Josef Wladyka (mentored at NYU’s film school by Spike Lee, who put his imprimatur on as executive producer) never loses sight of the wrenching personal consequences. Beyond the suspense of a brutal and picaresque aquatic adventure, the violence in this harrowing odyssey escalates as horrible choices lead to terrible consequences—morally and physically—for the future of this Pacific community.

Lastly, the treatment of women in India has roiled the news and government. For context, Vara: A Blessing is a sensually poignant immersion in the cultural resonance and social limitations of rural village life. In director’s Khyentse Norbu’s third feature (best known is 1999’s The Cup), the modern world tempts the younger generation with the promise of economic advancement and freedom from hidebound restraints, but in exchange for superficiality and spiritual loss. Which will win out and who will benefit is not predictable or stereotypical.

Based on a story by leading Bengali writer Sunil Gangopadhyay, traditional arts are still inspiring two young outcasts. Lila (Shahana Goswami), a star student of classical Bharatanatyam dance, trains under the strict tutelage of her mother (renowned dancer and choreographer Geeta Chandran). She so throws herself into her dancing role as Krishna’s consort Radha in rehearsals for temple ceremonies that she catches the attention of a handsome low-caste sculptor apprentice, Shyam (Devesh Ranjan).

He bravely challenges local propriety by asking her to secretly pose as a model for a goddess statue—they’re not supposed to be alone together. However, the cynical older generation brutally enforces destructive prejudices and superstitions wrapped in the beauty of cultural continuity. (Reflecting the mix of the old and new, Nitin Sawhney’s score splendidly blends ancient and contemporary music.) Meanwhile, the younger generation finds ways to reach some artistic and romantic fulfillment, or at least bittersweet survival.

Leave A Comment