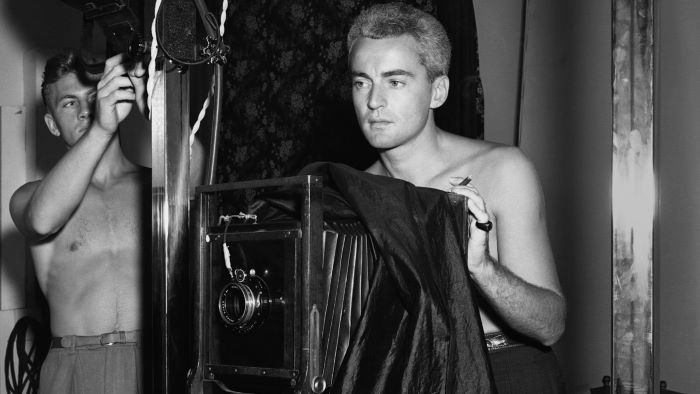

George Platt Lynes working in his studio with an assistant in Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes (Greenwich Entertainment/A Precious Few LLC)

![]() Gay photographer George Platt Lynes may not be considered particularly canonical as an artist, but Sam Shahid’s exquisitely wrought documentary will likely generate wider and deeper interest in Lynes’s work.

Gay photographer George Platt Lynes may not be considered particularly canonical as an artist, but Sam Shahid’s exquisitely wrought documentary will likely generate wider and deeper interest in Lynes’s work.

Born in New Jersey in 1907, an ambitious Lynes moved to Paris in 1925 and became part of Gertrude Stein’s salon. He then briefly went to Yale but dropped out, the conventionality there bored him. Lynes then moved to New York and met prominent writer Glenway Wescott and publisher/museum coordinator Monroe Wheeler. The three lived as expatriates in Paris and became lovers. Lynes’s artistic career began to flourish through portraits of prominent figures such as Stein, Collette, and Katharine Hepburn. The film speedily moves through Lynes’s flashy rise within the medium of commercial fashion photography. The pictures are stunning to behold: a dizzying array of influences and styles with luminous light and stark shadows—elements of the surreal akin to the avant-garde modernism of the time.

The film doesn’t shy away from Lynes’s sublime nude photography, rather it ravishes in it, as if to visually reclaim a suppressed history. Male nudes from the 1930s were rare. He began with erotic self-portraits, and later photographed ballet dancers and models. (Interestingly, his nude photographs would sometimes be staged in the same studio with the same props of his fashion magazine shoots—highlighting the dichotomy of private and public art.)

There is an impression of wildness and lightness in the way Lynes and his cohorts lived within the artistic circles of the late 1920s and 1930s. Later, the McCarthy-era becomes a turning point, personally, politically, and artistically. The austere beauty of Lynes’s fashion photography begins to fade in the shadows of rising stars like Richard Avedon. His drive and ambition do as well, and his health quickly declines. He eventually succumbs to lung cancer in 1955. Before his death, Lynes destroyed much of his work. However, because he had given many of his nude negatives and photographs to an interested Dr. Alfred Kinsey in the early 1950s, some of his vital work remained preserved at the Kinsey Institute in Indiana. In thinking about his legacy, Lynes felt the Institute could potentially protect his work.

This is one of the more intelligent documentaries of an artist I can think of in recent memory. It reveals Lynes thoroughly to the viewer, but also offers a sense of mystery (a box of Lynes’s output was requested by him to never be opened). The interviewees, including some of Lynes’s old friends and models, are well informed, not flashy celebrity types, who talk emotionally and eloquently about the photographer and his work. The inviting score by Sarah Lynch invokes the spright slyness and melancholy of its subject. Conor McBride’s editing smoothly guides the viewer through an array of period footage and Lynes’s arresting photographs. The documentary and its talking heads persuasively argue for a larger, prominent exhibition and resurrection of Lynes’s work as a whole.

Leave A Comment