It may have taken until the autumn to get there, but finally 2021 started to resemble the pre-Covid moviegoing schedule, where every week a number of high-profile movies debut. Currently, filmgoers are faced with a deluge of films that were held back because of the pandemic and are finally seeing the light of the projector, as well as productions that were shot with Covid protocols in place, arriving in time for awards season. Now at least, there are many movies up for grabs. Last year, it was already a given by September that Nomadland was the likeliest Best Picture Oscar candidate. If it was released this year, it would likely have been nominated, but it would have faced formidable competition.

In some ways, this is the best of times for a film buff. New selections are more readily accessible than they ever have been, either in theaters, which are steadily coming back to life after a long shutdown—knock on wood—and online. An acclaimed Ukrainian film premiering in New York City or Los Angeles can be streamed in Davenport, Iowa, on the same day, thanks to virtual cinemas. Viewers no longer have to wait too long to see a film; the window has vastly shrunk between the theatrical release and its online/video on demand premiere.

Overall, it was a very good year at the movies. Plenty stood out, which made compiling this list, alphabetically ordered, relatively easier than most years. For the first time, one director has two films on the roster: Ryusuke Hamaguchi, who, by this right, should be considered the filmmaker of the year. He did not come out of nowhere. His films have recently debuted in festivals and received limited distribution, but he really broke out in North America when Drive My Car premiered at the New York Film Festival after it won Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival in July. Also making his debut here is Wes Anderson, who went full-on twee with The French Dispatch, and Todd Haynes, for his first solo documentary effort, The Velvet Underground.

However, it wouldn’t be much of a list without some divisiveness, and I can think of at least one movie below that achieves that, one which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Also, this site’s objective has always been to highlight work that might need extra attention, and so the addition of two titles that may have escaped notice play an important role in this year’s top 10. Kent Turner

This ambitious documentary looks at who does what in China’s modern-day economy—and what that all adds up to. The early scenes center on factory workers, whose machine-like precision is put to the test producing everything from clothing to sex toys, albeit fast and in enormous quantities. Director Jessica Kingdon frequently packs the frame, placing her subjects in the foreground of cavernous spaces full of the goods they’re making. Then the focus shifts to other burgeoning industries: a livestreaming marketer, a bodyguard for organized crime, or a butler for the dawning, homegrown millionaire set.

Kingdon makes pointed commentary without ever hitting the viewer over the head. Her tone is detached, the camera acting as a silent observer as her subjects go about their lives, which for seemingly everyone but the wealthy is constantly under the influence of the Chinese government. (Ascension arrives at a very interesting period in the nation’s history as President Xi Jinping has been taking steps to crack down on what he views as the outsized influence of the very rich). As such, some of the most telling moments occur when those most under the state’s thumb nevertheless speak their mind, the idea seeming to be that although the Chinese economy is an enormous engine, those driving it still have a degree of free will. Phil Guie (available on Paramount+)

Japanese filmmaker Ryusuke Hamaguchi succeeded twice this year, first with Drive My Car, a serene three-hour intimate epic that proves how misguided is the animosity toward three-hour-plus movies. Hamaguchi adapts and expands a short story by Haruki Murakami, centering on Yusuke Kafuku (a stoic Hidestoshi Nishijima), a theater actor and director traveling to Hiroshima for an artistic residence. Two years earlier, his wife died from a brain hemorrhage days after he found her cheating with another man (all this occurs in the 40-minute prologue before the opening credits). While dealing with grief, his goal is to stage Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya with an experimental approach, performed in different languages (including Korean sign language) by each actor, one of whom is the former lover of his wife. In the meantime, a young female driver—skilled and mostly silent—has been assigned to take care of Yusuke’s transportation, initially against his will.

Part of the film concerns a friendship in the making with such an odd pair, two introverts who prefer silence. Delayed confessions, insightful conversations, dinners with new friends, rehearsals among adversaries, moments and cigars shared in quietude fill the spaces in-between work and creation. Art and life blend together in a daily round trip, from one quiet epiphany to the next. Blessed be long movies! Guillermo Lopez Meza (in theaters)

Danish filmmaker Jonas Poher Rasmussen ingeniously uses animation to convey the true story of his friend (called Amin in the film) who, as a teenager, escaped from Afghanistan to Denmark during the 1980s Mujahedeen rule. Graphic illustration, both expressive and realistic, is an ideal choice to depict both riotous and subtle emotions in his harrowing journey, while also masking the identities of Amin and his family. Newsreel footage from the era adds documentary realism as we, step by step, follow the trajectory of a refugee’s journey that involves corrupt police, human traffickers, and a few kind strangers.

Forced to lie and deceive from a young age and with indescribable traumas haunting his memory, Amin holds secrets from his past close to his vest. He even deceives Rasmussen, his friend since he obtained political asylum in Denmark at age 15, as well as his gay partner, who imagines a traditional future for the two of them. During the filmmaking process, Amin reveals the deceptions that gripped him in fear for so long while stretched out on a couch in an ersatz psychotherapy session.

A triple threat as one of this year’s best documentaries, best animated films, and best international films, Flee is an engrossing and moving story of a complicated migration from Kabul to Copenhagen. Rania Richardson (in theaters)

Of all Wes Anderson movies, The French Dispatch is the Wes Anderson–est. This film, a hermetically sealed bubble, has no interest in initiating newbies. If you feel anything less than enthralled by the writer/director’s particular vision and style, this is not for you. If you’re a fan, though, it’s delightful. Simultaneously an homage to The New Yorker and mid-20th century French cinema, it is also Anderson’s take on the anthology film: the visual representations of a trio of stories from the fictional titular magazine.

This is decidedly not a deep film. It doesn’t have the same wistful melancholy as Moonrise Kingdom or the clear-eyed wisdom of The Grand Budapest Hotel. No, The French Dispatch is a confection. It’s the kind of movie that critics of Anderson’s work, the ones who say his films are artificial and fussy, will point to with accusing fingers. However, it’s a gift to his fans—a fan film made by the filmmaker himself. The cast is extraordinary, and everyone seems to be having the time of their lives. Chock-full of sight gags and arch dialogue and with a production designed within an inch of its life, it’s an absolute delight. Paul Weissman (available on demand)

Director Fernanda Valadez’s visually arresting and layered debut film blends documentary-like realism with an emotionally driven quest that features wonderfully reserved acting. Unmarried 48-year-old Magdalena (Mercedes Hernández) has lost contact with her only son, Jesús (Juan Jesús Varela), who left home two months earlier to head north to the United States from central Mexico. Dozens of bodies have been found in a hollow grave along the bus route heading to the border that was hijacked by unknown assailants. However, the teenager’s body hasn’t been found, only his bag.

Magdalena simply wants to find her son, and her story line converges with that of Miguel (David Illescas), a young man recently deported from the States back to Mexico, and their paths unknowingly intersect at a migrant shelter before they meet face to face out in the countryside, which has become a war zone. A brief sequence involving a pickup carrying a half a dozen passengers down a dirty backroad is a telling example of Valadez’s deft direction: The truck has to stop, the road has been blocked by a militia, and a camouflage wearing, masked man armed with heavy weaponry inspects the passengers, all of whom instinctually know not to look at his face and to become as invisible as possible in order to live.

You can’t go home again. Be careful what you wish for. All these sayings apply here in Valadez’s harsh diagnosis of Mexican justice. Like The Power of the Dog, Identifying Features builds tension as it moves along. So assured and impactful is its ending that it can get away with three or four powerful twists. KT (available on demand)

Jane Campion has long since proven herself as a master at portraying genuinely unsettling states of being. The Piano, In the Cut, and Top of the Lake, to name a few, each overturned our expectations. With her characteristic skill directing actors to convey a mixture of motives, her elliptical use of imagery, and her instinct for mood over plot, The Power of the Dog is a formidable addition to her body of work.

Set on a ranch in 1925 Montana against looming mountains and seemingly endless skies, it looks, at first, like a Western, yet it is in fact a mysterious, brooding drama that does not leave the viewer with a sedate interpretation of the events therein. It is more preoccupied with waiting than supplying action, with the violence within than its outward manifestations. It is also Campion’s first film to deal almost exclusively with men and masculinity, and she approaches this subject with insight.

Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch) is a conflicted, contradictory man who refuses to tolerate the aspects in others that he cannot tolerate in himself. Cumberbatch gives an affecting performance that eclipses many of his other roles. By the end, you’ll be convinced that the forbidding, Western drawl is indeed his real voice. Andrew Plimpton (Netflix)

Zeytin was born to be a star. The camera can’t stay away from her as she roams Istanbul’s magnificent, crumbling streets, radiating the mystique of a loner and a dash of regal charm. Passers-by can be heard remarking on her good looks, and strangers clamor to have her stay overnight. For all her charisma, Zeytin’s line readings aren’t much; she’s one of the unhoused dogs at the center of Elizabeth’s Lo’s beautiful and bittersweet documentary.

Cameras take a dog-level view of the lives of Zeytin and other canines as they amble their way through a dense, detailed urban landscape, sometimes fighting for survival and sometimes seeming to enjoy a freewheeling life of leisure. The dogs dodge cars, sit calmly in traffic, and, like the world capital’s human citizens, help themselves to a wide array of food on offer.

The people around them don’t always fare so well. A group of homeless Syrian teens, who welcome Zeytin into their squat, tries to adopt a dog, although they can barely fend for themselves, and the boys’ need for love and something to take care of shines through an overlay of addiction and poverty. Elsewhere, the dogs easily coexist with Istanbul’s roiling tableau of vendors, cops, feminist protesters, quarreling couples, tourists, and other animals.

By following the dogs, filmmaker Lo provides in passing a portrait of an overpopulated city and its endlessly shifting human masses. Part picaresque adventure, part meditation on existence, Stray holds a lot to reflect upon within a deceptively simple structure. Caroline Ely (Hulu and on demand)

Julia Ducournau hit the scene with Raw, a gnarly cannibal coming-of-age film that celebrated sisterhood. That film was like a sleek Ferrari coming out of nowhere, running you down and speeding off before you had a chance to glean what was happening. It was funny, fierce, gory, and touching. A new kid was decidedly on the horror block.

The top prize winner at this year’s Cannes, Titane is another vehicle altogether, more of a roadster cobbled together from different parts. It’s big and bulky, but it still has enough juice in the tank to take you down hard. The plot itself is genuinely absurd. Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), a psychopath with PTSD from a car accident, which resulted in a titanium plate inserted into her skull, kills a bunch of people, one during sex, and then hides from the cops by impersonating a boy who has been missing for 10 years. Also, she has sex with a car and becomes pregnant with its offspring.

The movie works because Ducournau has serious skills, a sense of humor, and knows a plot will work, no matter how absurd, if there’s substance to the mayhem. Here, as in Raw, it’s about family, actual or created, and how familial love can change and save you. She’s definitely a disciple of David Cronenberg, but while his films have an icy, clinical reserve to their body horror delights, Ducournau understands that a body encases a heart, and she is possibly more interested in that. PW (on demand)

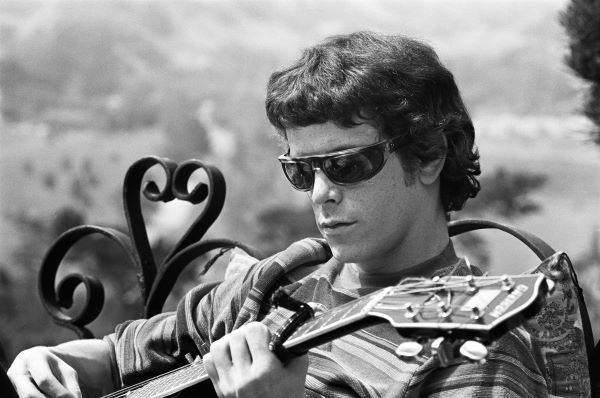

For his look back on the seminal rock band the Velvet Underground, Todd Haynes held back from using narration and only included the voice-overs or interviews of those who came within the group’s wide-ranging orbit. He also sat down with surviving band members Maureen “Mo” Tucker and John Cale. Here, Baudelaire meets Bowie.

Via multiple split screens, Haynes has produced a kaleidoscopic and aural sensation, which alludes to, but without imitating, the group’s live performances, which were set against psychedelic visual projections. The bombardment of archival footage, home movies, and Andy Warhol’s 16mm films all enhance this dense and textured documentary, which prominently spotlights the self-taught guitarist/lead singer Lou Reed and the loquacious Cale.

The free flowing, first-person accounts disclose the drug addiction, sexual triangles (hello, Nico), and bruising ego battles, and more, making this the opposite of a hagiography. Because it touches on much larger themes than just rock history, the movie will entice those who only know the band peripherally. Others may come away with a whole new appreciation of its sound. For fans, it offers a front row seat to the band’s experimentations and rivalries. Finally, The Velvet Underground shoots toward the top of any list about New York’s flourishing cultural scene of the ’60s. KT (Apple TV+)

Is the world full of coincidences? Or are we just predestined to endure specific events? The conjunctions between the arbitrariness of chance and the certainties we call fate occur in the second of the two exceptional films directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi this year. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize at the Berlin Film Festival) works as a compelling case for anthologies. Without a direct connection among its three stories, they share the compassionate outlook of an artist who understands how miraculous and troubling a chance collision can be.

Two best friends discuss the new romantic relationship of one of them without suspecting they both love the same man. A former disgruntled university student schemes to ruin the life of a professor recently awarded a literature prize. And in the best of the bunch, two strangers believe they are close friends from the past in a case of mistaken identity, until they venture to erase the borders between “performance” and “reality” to find closure.

Not all these stories provide a satisfactory conclusion for their characters, but their experiences are transformative. Each one stars a female character who comes across as complex and fully fleshed-out in a matter of minutes. At the end of every tale, no one remains the same as before. We can only hope that the same would happen to us if we were in their shoes. GLM (in theaters)

Leave A Comment