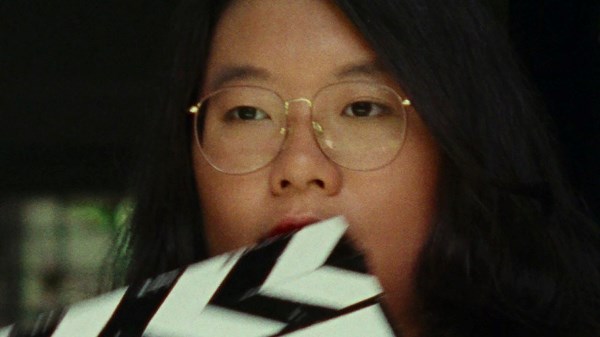

![]() In this sincere, engrossing documentary, director Sandi Tan looks back a quarter of a century at Shirkers, a quirky indie film she helped make that captured a mostly bygone Singapore. The catch is that the titular movie was never released, but its filming—led by a ragtag group of locals and one expatriate—has become the stuff of urban legend. The new Shirkers opens with Tan questioning whether her memory of making the film was just a dream, and given just how peculiar and twisty the behind-the-scenes story is, any of her doubts seem entirely appropriate.

In this sincere, engrossing documentary, director Sandi Tan looks back a quarter of a century at Shirkers, a quirky indie film she helped make that captured a mostly bygone Singapore. The catch is that the titular movie was never released, but its filming—led by a ragtag group of locals and one expatriate—has become the stuff of urban legend. The new Shirkers opens with Tan questioning whether her memory of making the film was just a dream, and given just how peculiar and twisty the behind-the-scenes story is, any of her doubts seem entirely appropriate.

The prologue features a lot of footage playing in reverse, underscoring the theme of going backwards in order to eventually move forward. To that end, Tan begins by recalling how she and Jasmin Ng became best friends as teenagers. Growing up in a swiftly modernizing but highly conservative society in Singapore, they shared a yearning to rebel against the expectations placed upon them. Through dizzying montages of photographs, postcards, letters, and homemade zines and collages, we get the idea of just how creative and unconventional they were.

Then around the same time that Tan and Ng were in high school, they enrolled in a filmmaking class taught by Georges Cardona, a highly charismatic and indeterminably older man who started hanging out with them socially. He and Tan and bonded over a shared love for the French New Wave, a connection reinforced during her first, desperately lonely year abroad at university. She grabbed the opportunity to take a long road trip with Cardona, which culminated with her agreeing to write a screenplay for him to direct. By the summer of 1992, Tan’s friends and family members had all signed on to help, despite the grueling shooting schedule she had devised to fit it into her summer break.

The screenplay for Shirkers boasted a wonderful tagline that conveyed Tan’s embrace of resistance to the status quo: “There are movers. There are shakers. And there are shirkers.” Yet given that a shirker is a person who runs away and avoids their responsibilities, both Tan and Cardona, ironically, prove to be the biggest shirkers of them all. In a brave move, Tan does not hide from her own mistakes, and some of the most compelling moments involve her and Ng revisiting the past in face-to-face conversations. Ng, who served as the lead production assistant, accuses her friend of essentially behaving like a prima donna and turning a blind eye to all kinds of problems because her film was getting made.

One of the big issues was the increasingly erratic behavior by Cardona, such as an incident involving a scene shot on railroad tracks: he waited until the last possible moment to warn the actors of an oncoming train. Tan hints that he derived amusement from such antics, and indeed, others, including another friend who worked on the film, Sophie Siddique, describe him as a manipulative sociopath with an inflated ego who was inept at actual filmmaking. Yet even then, what Cardona did after filming wrapped still registers as a shock. He disappeared with all 70 reels of footage and vanished.

Among the biggest tragedies of the never-finished film is that, based on the behind-the-scenes footage, it clearly brought together a passionate and excited community. There is footage of cast auditions with non-professional actors who always dreamed of appearing in a movie. Others eagerly volunteered because so few films at that point were shot in Singapore, and they really believed Shirkers could help change that. But Cardona’s actions also marked a betrayal of a tight-knit group of friends, which is what he, Tan, and company seemed to be, based on home video of them during late-night drives together.

The later section in which everyone involved with Shirkers is forced to move on with their lives feels understandably meandering. Milestones are presented in a highly compressed manner, reflecting Tan’s perception of them as years spent lost. But then comes a surprise development that sets up the film’s last leg as a detective story, the central mystery having to do with none other than Cardona. In her coming to terms with him, Tan does not come close to exonerating Cardona for the harm he caused, and which she frames as a collective loss of innocence for herself and others. Nevertheless, what she finds adds to a fascinating psychological portrait of a deeply flawed man.

Adding to the sense of poignancy toward the end is a juxtaposition of the film’s subjects with their past selves, as well as the Singapore of the early 1990s to the present day (which moviegoers recently got a look at through the hit Crazy Rich Asians). What Tan shows us is that although things inevitably change, it can be for the better. Fittingly, the film becomes the equivalent of a love letter from Tan to Ng and Siddique, basking in all they’ve accomplished over the years.

If there is any complaint worth levying at Shirkers, it is the lack of an update regarding the status of the completed version of the original film, which based on what we see, suggests something like Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless as filtered through the complex emotions of a precocious teenage girl—which makes sense, as Tan was exactly that when she first conceived it. Reportedly, the main obstacles to achieving a final, edited version are the soundtrack and audio recordings, which were lost to time (or Cardona’s indifference). While it is perfectly fine to have our appetites whetted by this fascinating documentary, what lingers is a feeling that until Shirkers 1992 finally graces the big screen, an injustice remains unresolved.

Leave A Comment