Mars at Sunrise attempts to bring an experimental cinematic consideration to the Israeli occupation, and has flashes of innovative success amidst didacticism and confusing imagery.

Its framing device is a visit to the West Bank by an Iranian-American tourist, Azzadeh (Haale Gafori), who narrates through poetry, from Shakespeare to Runi plus Gafori’s own lyrics, with the descriptions of “the Holy Land made so unholy” with weapons and “the Dead Sea—bowl of human tears.” She hires cab driver Khaled (Ali Suliman) to get her through traffic at a checkpoint outside Ramallah, but the sight of Israeli soldier Eyal (Guy El Hanan) arrogantly taking a long nap break, while the line backs up, sets off the driver’s posttraumatic stress flashbacks of the last time he was confronted by this soldier, two years earlier.

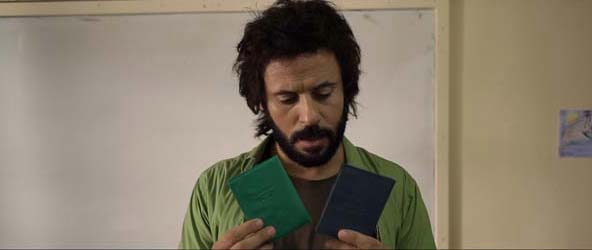

Khaled was then living an intellectual’s life in his artist’s studio in East Jerusalem, full of books and paintings, and teaching art at an elementary school. But when his house is appropriated by Israel, he’s deemed an illegal resident and loses his right to live and work there. His family keeps calling—his parents urge him to join them in Ramallah or his sister in Gaza. He tries to explain to his students how the “racist wall” changed his identity card color and “limits our freedom, our dreams, and creativity.” He compares his identity card with the substitute teacher’s: with one ID card he would be allowed to see the mountains but miss the sea; with the other ID card, to Gaza, where he could see the sea but miss the mountains. He tells them how he hopes “One day all these papers will have no meaning and will cease to exist.”

But when he tries to reestablish his studio in Ramallah, the Israeli soldier comes in, arrests him, keeps him awake in awful prison conditions, taunts him about his personal life and artistic ambitions, beats and kicks him—all to get him to collaborate. Despite this torture, Khaled maintains his sanity by holding on to his artistic sensibility through stream-of-consciousness images of creating art. As Eyal keeps accusing him of being with Hamas, Khaled declares “I am first of all an artist,” and there are powerful scenes of him later recovering from this awful experience by slowly returning to painting. Debut American writer/director Jessica Habie says this character was inspired by Palestinian artist Hani Zurob, who realized his talent by drawing graffiti and political posters as part of the First Intifada in the late 1980s.

The Israeli soldier is also having his own PTSD flashbacks and nightmares whenever and wherever he tries to sleep. Interspersed with Khaled’s vivid memories, these are far more confusing images, infused with Eyal’s guilt over accidentally shooting a boy. While the soldier also has artistic aspirations that are supposed to set up a parallelism between the two men, the stiff, weak performance by El Hanan, who has a background in radio and playwriting but not acting, weakens the clumsy attempt at mutual sympathy, especially compared to the impact of the internationally known Suliman (The Attack).

More effective is the moving soundtrack. Produced by Tamir Muskat of the Brooklyn-based world fusion band Balkan Beat Box, there are multilingual songs (in English, Hebrew, Russian, Yiddish, Farsi and Arabic) and a multitraditional instrument score by Itamar Ziegler and Mohsen Subhi.

Leave A Comment