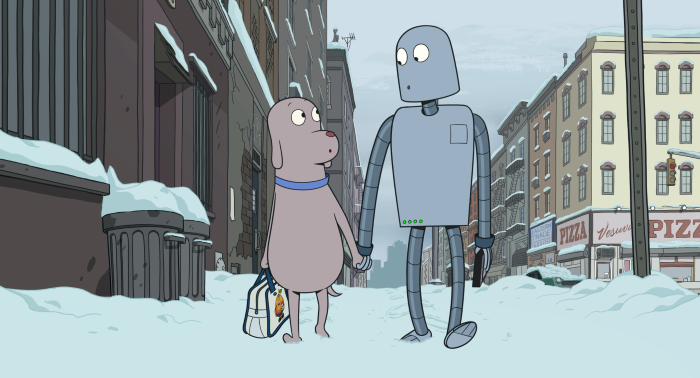

Dog and Robot in Robot Dreams (Arcadia Motion Pictures, Lokiz Films, Noodles Production, Les Films du Worso/Neon)

![]() A gimmick can only take you so far if it lacks sincerity. In that sense, the idea of a film made today “without dialogue” or in the style of silent cinema might seem like a mere artificial curiosity. Fortunately, Spanish director Pablo Berger has imbued his love for cinema and storytelling with beauty and honesty: first with the superb Blancanieves (2012), a live-action, black-and-white reimagining of the classic fairy tale presented with intertitles, and now with the animated Robot Dreams, also without dialogue, but where music and sounds are as vibrant as its colors. In both cases, Berger has crafted fantastical tales of great visual (and sonic) inventiveness that are as gorgeous to look at as they are emotionally bittersweet.

A gimmick can only take you so far if it lacks sincerity. In that sense, the idea of a film made today “without dialogue” or in the style of silent cinema might seem like a mere artificial curiosity. Fortunately, Spanish director Pablo Berger has imbued his love for cinema and storytelling with beauty and honesty: first with the superb Blancanieves (2012), a live-action, black-and-white reimagining of the classic fairy tale presented with intertitles, and now with the animated Robot Dreams, also without dialogue, but where music and sounds are as vibrant as its colors. In both cases, Berger has crafted fantastical tales of great visual (and sonic) inventiveness that are as gorgeous to look at as they are emotionally bittersweet.

Robot Dreams marks Berger’s first foray into animation, a format that, in the right hands, provides an artist with the tools to unleash the imagination without constraints. This time, the story is set in 1980s New York, an era before the internet and smartphones—it even dares to feature the Twin Towers. The protagonist, Dog, a dog of course, spends his lonely nights in front of the TV eating snacks, lamenting the lack of companionship and affection from another living being with whom he can share experiences and moments, as suggested by the glimpses into the windows of his neighbors, who are always in pairs (all animals of different species). As if to answer his prayers, the TV suddenly lights up with the question “Are you alone?” followed by an infomercial offering companion robots that can be assembled by the buyer. That night, Dog goes to sleep hopeful, knowing that the next morning he will receive a gift he has given himself.

When Robot, or the parts needed to assemble him, arrives at Dog’s home, the canine can’t contain his excitement, wagging his tail as he unlocks multiple locks, which reveal more about his personality than any soliloquy. When Dog assembles Robot, the process is watched by pigeons flying near his window, who flee in terror when Robot awakens like Frankenstein’s creature—Berger sprinkles the story with numerous nods to classic films. (In this world, some animals are humanoid, while some animals seem to be just animals.)

Once alive and functioning, Robot and Dog are ready to keep each other company during an unforgettable summer. Together they explore the city, complementing each other in their differences: Dog is somewhat rigid and rule following, while Robot is reckless and eager to explore the world for the first time. For example, Dog wants to teach Robot how to use a ticket to enter the subway, but Robot imitates the naughty reptiles that jump the turnstiles. Their common ground ends up being music, culminating in a beautiful sequence where they both start dancing to “September Song” by Earth, Wind & Fire, a song that later (in various versions) becomes a recurring motif.

However, at the end of the summer, an accident separates them. During a visit to Coney Island, Robot experiences the beach for the first time, but the combination of sand and sea prove fatal to his mechanism, leaving him immobile but conscious. Dog hasn’t brought oil, and is unable to lift and carry him home, and there’s no one to help them as they both fall asleep until nightfall. Robot communicates with his gaze for Dog to return home alone. (It’s extraordinary how the film achieves a rich dialogue of gestures that speak for themselves.) The next day, Dog finds a security gate announcing the beach will be closed until the following year. Subsequent attempts to trespass are thwarted by the security bull guarding the place and an arrest. Dog has no choice but to wait for the season to pass until he can finally return to the beach. Meanwhile, Robot remains alone on the beach, and that’s when the dreams that give the film its title begin.

Can we call it love at first sight? Friendship or romance? Is there room to labeled it as queer? What is the nature of the relationship between Dog and Robot, if one is the buyer and the other their product? This colorful fantasy doesn’t bother answering overly complicated questions, though it doesn’t lack emotional complexity worthy of adult consideration. It’s clear that Dog and Robot care for each other, and the longing to reunite gives a note of sadness that defines the film’s nature. Their respective nightmares give rise to imaginative sequences that reflect their fears and anxieties. In one, a snowman coming to life becomes a substitute friend for Dog, but ends up humiliating him publicly at a bowling alley. It’s a relief for Dog to wake up and find it didn’t happen, but then the absence of Robot is even more painful. Reality, meanwhile, is no better than nightmares. Nevertheless, Dog tries to move on with his life (and forge new relationships) while Robot waits for a rescue that ultimately comes in ways best left unrevealed.

As an animated film, Robot Dreams possesses a narrative clarity that could charm anyone, but this is not exactly a children’s movie. Its dissection of relationships and loneliness expresses aspects of desperation and longing that harken back to other recent melancholic romances with “what if” scenarios, like La La Land or Past Lives (comparisons that the film’s Spanish marketing has taken into account with posters inspired by these movies). As in those cases, the effect is devastating but not tragic. Our stories with others sometimes end. We do what we can within limits, and sometimes our nightmares come true, but they are not as horrible and more tolerable than we imagine. In any case, the ways we connect with others don’t always stay the same, but the irreversibility of bad timing is the same, no matter the era.

Leave A Comment