How to grieve properly when the object of your loss is not entirely gone? In the context of a zombie movie, this would probably be the last question anyone would ask while running for their lives. Yet during much of the Norwegian film Handling the Undead, the return of the dead doesn’t lead to a terrifying global crisis, but as an occurrence that alters personal and domestic dynamics in a way that is simultaneously mundane and painfully personal in the lives of three different families.

The living dead and the idea of a zombie apocalypse have fueled enough nightmares and fascination in the collective imagination through movies (and TV series) with a clear formula since the contributions from George A. Romero. Zombies are monsters, and if you knew their former selves before, be aware they are just a living corpse that wants to eat your brain. Recently, there have been some hybridization in the form of comedy (Zombieland, Shaun of the Undead), musical (Anna and the Apocalypse), and even a Twilight-like romance (Warm Bodies), but horror movie devotees know very well what they want and expect from these films.

So, Thea Hvistendahl’s debut feature film stands out for its confidence while not seeming to appeal to this audience. Even the title sounds too polite to describe a hostile phenomenon. For three-quarters of its running time, it works better as a chamber drama than horror entertainment. The dead come back to life following an unexplained phenomenon, but they do so in such a silent and discreet way that it almost seems like a daily occurrence. (Perhaps there’s an inside joke here about the stoicism of Nordic countries, but the onscreen serenity confuses more than it amuses).

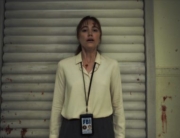

In the absence of surprise and hysterical screams, there is instead somber drama and a sense of disquiet: Anna (Renate Reinsve), a nurse, has recently lost her young son; Tora (Bente Borsum) comforts her dying soulmate, Elisabet (Olga Damani); and a father (Anders Danielsen Lie) receives the news that his wife, Eva (Bahar Pars), has died in a car accident. All of them have their mourning interrupted by the unexpected resurrections of their loved ones. They return, however, in undead form, capable of moving and making some noises but completely detached from who they were when they were alive. Although characters overlap in some spaces, like in a hospital, their respective stories do not intersect, nor do they interact. (Fans of The Worst Person in the World will surely be disappointed by the missed opportunity to have Reinsve and Danielsen Lie in the same movie).

Handling the Undead is slow in its development, sensitively observing the effect that the return of dead loved ones have on the living. Hvistendahl initially replaces the horror and violence typical of these spectacles with images of desperation and reconciliation: a grandfather digging up his grandson, two elderly women dancing to the rhythm of “Ne Me Quitte Pas,” a father preparing his children to visit a mother who will probably look unrecognizable to them.

Reinsve is effective in expressing rage and frustration at the situation, accepting this new strange reality in which her suffering is prolonged with the complication of hope. Along with her father, they decide to travel to a remote house in the countryside to protect the exhumed child (perhaps when global alarms are finally raised?), who appears in an early state of decomposition but capable of moving his limbs and opening his eyes.

Based on its first hour and a bit more, Handling the Undead sounds almost Bergmanesque, setting the stage to deeply explore ideas about death and grief. The problem is that the film then becomes uninterested in assuming this intellectual commitment when it finally relies on a third act that brings back the demands of the genre it so diligently sought to distance itself from earlier. When it finally decides to embark on true horror, it’s too late.

The disturbing and cruel scenes near the end are brief as well as belated, unable to wake the hypothetical horror lover who ended up being lured by the marketing (although there is one scene involving a rabbit that is chilling). The result is more brilliant in theory than in execution, and could be described as frustrating and boring and a waste of splendid actors in an insufficient drama that ends up aspiring to be just another zombie movie after all. It’s perhaps only surpassed by Jim Jarmusch’s pointless The Dead Don’t Die in its unlikelihood to inspire repeated viewings.

Leave A Comment