![]() This brief, fascinating documentary about incarcerated men who have been all but forgotten by the rest of the world, has itself been lost since 1987. Directed by Werner Herzog’s longtime producer, Walter Saxer, it was only screened once, in Switzerland. The Cinémathèque suisse and Cineteca di Bologna have restored it, revealing a film that at once feels contemporary and apocryphal. It begins with grainy footage of a prison riot in Peru. The camera is shaky, and reports indicate that the angry prisoners will soon start making executions if their demands are not met. Soon, one of the prison staff is killed. The prisoners, we are later told, meet an equally violent end.

This brief, fascinating documentary about incarcerated men who have been all but forgotten by the rest of the world, has itself been lost since 1987. Directed by Werner Herzog’s longtime producer, Walter Saxer, it was only screened once, in Switzerland. The Cinémathèque suisse and Cineteca di Bologna have restored it, revealing a film that at once feels contemporary and apocryphal. It begins with grainy footage of a prison riot in Peru. The camera is shaky, and reports indicate that the angry prisoners will soon start making executions if their demands are not met. Soon, one of the prison staff is killed. The prisoners, we are later told, meet an equally violent end.

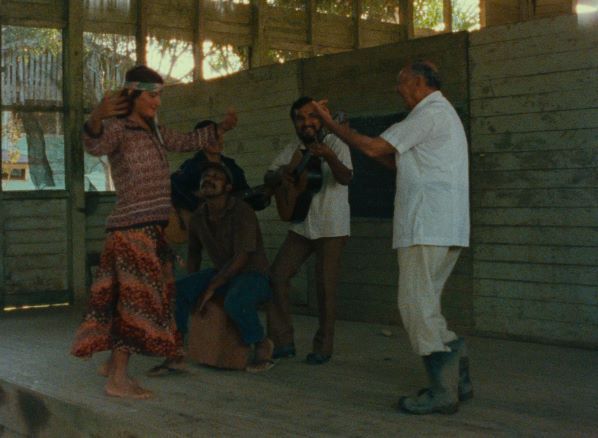

The rest of the film, however, is set not in this prison but in its polar opposite. Close to the Amazon rainforest is the Peruvian prison colony of Sepa, which was founded, we are told, as a place to send excess prisoners when larger prisons became overcrowded and unruly. Here, for the most part, the prisoners are not confined but allowed to roam freely and even sail boats down the river. The first three inmates we see are singing a jaunty song on a front porch in a place that looks more like a dilapidated farm than a prison. The warden, with some exceptions, seems to be someone the prisoners trust rather than a malicious disciplinarian. Significant others are allowed to come live with the incarcerated. The prisoners keep busy in numerous ways, largely by contributing to farm production, and the priest in the colony’s church is incredibly sympathetic.

Saxer takes us on a tour of this facility, detailing its operations, introducing us to its various inhabitants and their stories, all the while highlighting Sepa’s uniqueness in the world of prisons. Often, the prisoners have positive things to say about their situation. Much of the footage has a spontaneous, intimate, offhand quality, and scenes ease gracefully between interviews with its subjects and more casual footage of them at rest or at work, singing songs and the like.

Saxer gives space to various dissatisfactions the inmates might have. Early on, a group argues with the warden about why it takes so long for their release papers to be processed. One accuses him of money-grubbing, yet the warden handles the situation well and placates even the angriest among them. Yet the chief problem with Sepa seems to be its remoteness. Consequently, their papers for release are never processed in a timely manner, if at all, and whatever economic benefits might be possible from the agricultural work they produce goes unrealized. Therein might be Saxer’s most trenchant social criticism, that the world would be better off with more places like it, and that Sepa would be better off with more support from the world.

Saxer’s objective is clear, especially by the end: to advocate for the colony as an alternative to the inhumane prison-industrial complex. As such, its rescue and restoration will certainly be seen as timely. Audience members’ appreciation of it will doubtless hinge on the degree to which they trust Saxer’s account. Even though I share Saxer’s moral stance, there were times I wondered if he was leaving out details (more volatile explosions of anger) that might be inconvenient to the picture he wanted to paint.

Still, the documentary deserves credit for reminding us that many seemingly contemporary ideas have been around for a while. This would make a solid double bill with the 2007 meditation-centered documentary The Dhamma Brothers, which also proposes alternative forms of rehabilitation.

Leave A Comment