Most of us have moments when we are not comfortable in our own skin and not sure of who we are. Most of us might switch jobs or significant others, maybe move to another city, possibly change careers.

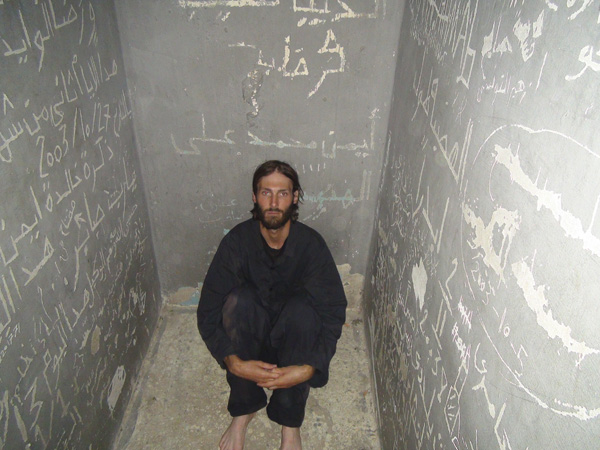

Matthew VanDyke, in the documentary Point and Shoot, takes a bit of a different tack. Having been a coddled, only child obsessed with movies and video games and enamored of the film Lawrence of Arabia, he decided to travel across Africa as a photojournalist and then return as a fighter in the Libyan revolution. After obsessively filming for four years, he came to director Marshall Curry, who edited VanDyke’s footage and then sat him down for an interview, which is intermittently disbursed throughout.

It’s a fascinating piece. We hear from VanDyke’s girlfriend, who is at first happy that he will be forced to care for himself, even if he will be gone for a long time. VanDyke naively considers his travels a “crash course in manhood,” and he decides to film himself so he can be the star of his own movie. It starts off innocently enough as he drives around the North African plains learning how to wheelie and meeting the locals, but soon he feels that he need to do something that matters. He gets work as a freelance journalist but fairly quickly abandons any objectivity by acquiescing to soldiers’ request in Afghanistan to stage shots to make them look cool. Eventually he heads to Libya and finds a group of like-minded motorcycle enthusiasts.

Once he returns home, he only stays for a short while before revolution breaks out in Libya. And it isn’t particularly clear to him, or us, if he’s going to help his friends, to affect change, or if he just wants an adventure or a combination of all three.

This part of the film is the most interesting because we get a grounded eye-view of an Arab Spring revolution and because we see the fracturing of VanDyke’s somewhat deluded thesis. Once he is filming and soldiering against Muammar el-Qaddafi’s forces, he’s conflicted. What should he be focusing on? His fellow soldiers want him to film because to them this is history. He wants to fight because he wants to be a part of history. Ironically, when he gets the chance to take someone out at close range, events don’t go quite as planned.

VanDyke narrates the film, and the director does not interject much in the interview. This leaves a wide-open field for an audience perspective on what to take away from VanDyke’s adventures. Some will surely see this as another case of macho white man hubris. And it possibly is. What I see is something different. I see a man attempting to create an identity that’s external from his inner self. However, the idea of action in itself being an impetus of change without an adjustment in inner thought doesn’t quite work. And he can’t really tether his wartime role to who he really is.

His “crash course in manhood” is the type of high-concept idea that works in movies, not so much in real life. So, though Matthew VanDyke has lived a life of action and absolutely got himself out of his mom’s basement, what he learns (hopefully) is that self-deception and self-aggrandizing do not equate peace. And don’t necessarily bring comfort. To judge him negatively would be ignoring the same qualities that lie in everyone.

Leave A Comment