Spoiler alert: Unlike several of this past year’s other touted musician bio-documentaries—Amy, Janis: Little Blue Girl, and Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck—saxophonist supreme Frank Morgan did not overdose on drugs. Sound of Redemption: The Frank Morgan Story has resonances with the usual Behind the Music tales of success, addiction, recovery, and comeback. However, the strong evocation of the lesser-known bebop jazz scene in segregated Los Angeles—and within San Quentin Prison—and the emphasis on his prodigious musical talent make this film cooler.

Morgan’s life is MC’ed by trombonist Delfeayo Marsalis at a 2012 all-star tribute concert held in San Quentin in the same chapel where the frequently incarcerated Morgan, along with many other jazz players/heroin addicts who cycled through the cells in the 1950s and 1960s, performed together in an exclusive big band. (I’ve seen fictionalized versions of such shows in several prison TV and movies, but hadn’t realized that it was based on this true story.)

Interviews with relatives, exes, friends, fans, managers, and fellow musicians, as well as a few archival interviews with Morgan himself, reveal he was born into music. His father, Stanley, was the guitarist for the Ink Spots, a popular black vocal group of the 1940s that was inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame as an “Early Influence” of R & B and doo-wop. All note how his son’s life changed the night in 1940 when he heard Charlie “Bird” Parker play in Detroit, and the teenager immediately switched from guitar to the saxophone.

By the time Morgan went to live with his father in Los Angeles, he was practicing around the clock, such that when he snuck into the famed segregated clubs along Central Avenue, he was invited to join bands when he was 14. (Downtown LA is described by one historian as “Mississippi with palm trees.”) A high point of his teens was backing up Billie Holiday all through her three-month residency at Club Alabam (compared here to the Cotton Club in Harlem). He proudly remembered: “She used to make me cry. She made me part of the act: ‘There goes that little sax player, crying again!’” He was mentored by another woman in the jazz world, “trumpetiste” Clora Bryant, who tells funny anecdotes of chaperoning him when he was underage to nude Hollywood parties thrown by a bohemian art patron.

And always there were drugs around being used by his idols. A friend strongly makes the case that the pressure of racism drove black men, in particular, to seek release in heroin, but Frank’s half-sister insists their father was a violent man whose abuse haunted his children. (The family felt that sending Morgan to live with his grandmother at her brothel in Milwaukee was an improvement—the geography of his early life is confusing.) Certainly, the legend developed that the only way to achieve Bird’s “happy/sad feeling” on the sax, as he played his instrument to the bebop max, was by taking drugs. Bird, though, was upset about the negative influence he was having on Morgan. Ironically, as the news broke that Bird died in 1955, the musicians left their clubs to shoot up in memorial.

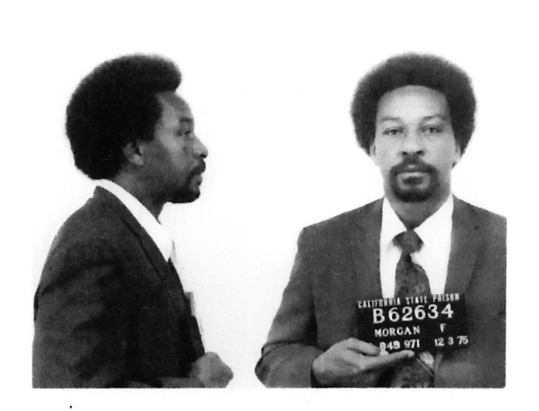

Morgan and his close friends needed more and more money to support their habits. Almost 30 years in jail are documented through a montage of ever-aging mug shots, accompanied by stern voices reading arrest records, parole reports, and prison evaluations of his behavior. Several ex-girlfriends and ex-wives talk of loving relationships (documented in beautiful photographs) until he couldn’t hide his drug use any more. Even his father reported him to the police.

Morgan frequently landed in the San Quentin All-Stars. At various times, that unique band included the likes of saxophonists Art Pepper and Dexter Gordon, along with singer Ed Reed who is interviewed extensively. They attracted long lines of outsiders seeking to get in for the Saturday night performances, where the bandmates wore tuxedos made in the prison tailor shop and were treated to special meals. For Morgan, methadone made it possible to get addiction, and his criminal record, under control by 1985. Jazz critic Gary Giddins reports on the fevered anticipation when Morgan got his sax out of a pawn shop to dare a comeback in New York City. Another fan of these sessions, and the subsequent recordings (Morgan’s legacy includes 17 albums), is crime thriller writer Michael Connelly, who is frequently featured and executive produced this documentary as a tribute.

Throughout this tumultuous story, director N.C. Heikin effectively keeps the music upfront. (Her first documentary, 2010’s Kimjongilia, cleverly used the outsize music and dance propaganda pieces of North Korea to illustrate the memories of refugees.) Labeled prominently onscreen are the titles and composers (Ellington, Gillespie, McCoy Tyner, Mingus, Parker, as well as Morgan) for each piece played or heard, a practice too rare in musical documentaries and one that makes this film more accessible for non-aficionados.

The San Quentin tribute concert features bassist Ron Carter, pianist George Cables, ferocious drummer Marvin “Smitty” Smith, and saxophonist Mark Gross, who in this context looks like a pastor. But the highlight is young alto saxophonist Grace Kelly. She speaks movingly about being his granddaughter-like protégé. By the time she blows her horn to play “Over the Rainbow,” just about everyone is tearful. New fans of Morgan’s work will be missing him, too, and grateful for this introduction.

Leave A Comment