Over the course of the last decade, the all-nonfiction film festival DOC NYC has become one of the largest such events on the circuit, joining ranks with Toronto’s Hot Docs and Britain’s Sheffield Doc/Fest.

DOC NYC has continuously grown, and this year it offers more than 100 titles, reportedly becoming the country’s largest documentary festival. Perhaps to help the overwhelmed moviegoer select options, the programmers have broken down the slate into somewhat convenient sections: “Modern Family, “Portraits,” “Fight the Power,” and so forth. Ticket buyers will also be well served to pick à la carte, seeing a little bit of this and a little bit of that, because of the wide array of films and genres and the consistently high level of filmmaking. The following are seven documentaries that are recommended, or of note, more or less in order of preference.

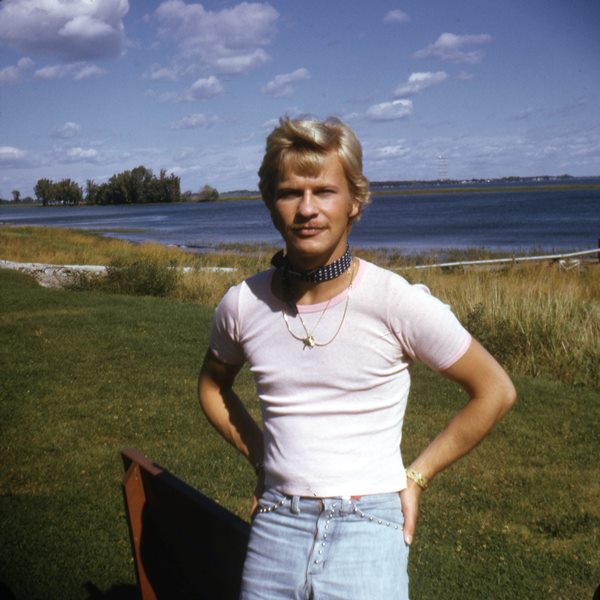

Based on Richard McKay’s 2017 book Patient Zero and the Making of the AIDS Epidemic, director Laurie Lynd’s illuminating and arresting documentary Killing Patient Zero will make you rethink the established recorded history of the early days of the AIDS epidemic, namely as recounted in Randy Shilts’s acclaimed 1987 investigation And the Band Played on: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. In that 600-page work, there were roughly 11 pages devoted to the French-Canadian flight attendant Gaëtan Dugas, who Shilts pinpoints as Patient Zero, responsible for spreading the disease across the country. Dugas died of AIDS in 1984. As explained by William W. Darrow, who conducted a cluster study of hundreds of men, including Dugas, for the Centers for Disease Control, the label patient Zero was a misnomer. This is among other alarming revelations in this debunking film, which succeeds in clearing Dugas’s scapegoat status.

Through portraying the life of Dugas through fond and frank reminisces from friends/colleagues, the film also vividly lays out the context of the gay liberation movement in North America and how it quickly had to confront the AIDS epidemic and the homophobic backlash. Lynd also features shocking audio from a news conference in the early ’80s, in which acting White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes flippantly and proudly tells the press corps that no one in the administration knows anything about the lethal epidemic.

Production company Danish Documentary is on a roll this year, having helped produce The Cave, The Kingmaker, and Eva Mulvad’s engrossing Love Child. (Mulvad is one of the founders of the female-led enterprise.) The film follows graying fortysomething Sahand, thirty-odd Leila, and their young son, Mani (rocking a bowl haircut) as they leave Tehran for Turkey and seek asylum. Married to an abusive drug addict, Leila began a relationship with her fellow English teacher Sahand, and they had a child—she was able to convince her husband that the boy was his, but she wasn’t able to persuade him to grant her a divorce, a husband’s right under Iranian law. (Her other options are legally complicated.) Shot over the course of six years, the well-edited film marks transitions within the family, especially for Mani, who at first has no understanding of his family’s political situation—early on, he lashes out at Sahand, disobeying him and calling him an “old hag.” Ouch!

The camera closely embeds within the family, celebrating birthdays and recording tense arguments that take place when Mani is out of the room. The film opens onto a unique view of refugees. Unlike, say, the recent Midnight Traveler, which followed an Afghan family seeking refuge in many European countries, the Iranian family settles into a comfortable and standard apartment on the outskirts of Istanbul, Sahand finds construction work (working late and coming home after Mani’s bedtime), Leila teaches English again, and the adults have mental health services available to them. However, the couple becomes tangled in red tape. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees considers the parents as having two separate cases, since they are not married and it deems Sahand’s circumstances as not political. Unusually for a documentary, the outcome of the petitions might have viewers on the edge of their seats.

News junkies should make the pleasurable Letter to the Editor a priority. Since 1980, director Alan Berliner has continuously compiled thousands of photos clipped from his favorite newspaper, The New York Times, and he bombards viewers with the rapid-fire edit of more than 7,000 photos from his archive. Finding inner connections among an extensive range of subject matter, Berliner narrates and calls his film “a missive to the future” in the event that the daily broadsheets go the way of the dodo. The result is, as he says, a time machine. He has also composed a love letter to the free and independent press that has been under attack by the Trump administration. The soundtrack includes Wagner, Puccini, and music from TV and radio news programs, like the theme for the BBC World Service; it’s an all-news production in every way, shape, and form. Those who are not in New York City for DOC NYC fortunately have the option of seeing this when it airs on HBO on December 4th.

Like Killing Patient Zero, Karen Bernstein’s uninhibited and rollicking I’m Gonna Make You Love Me also returns to New York of the 1970s and ’80s. Brian Belovitch left his homophobic and abusive upbringing in Providence for the Big Apple in 1974. Tiring of trying to conform to the macho gay image of the time, he began transitioning. Now going as Natalia, she legally married her hometown boyfriend in 1980 and became an army wife, stationed in Germany selling Tupperware—and grew restless. She returned to the city and transformed into a nightlife celebrity, now going by Tish, belting out Motown Tunes (hence the title) with Village Voice gossip columnist Michael Musto—he describes her as a “kooky Cyd Charisse.” However, using heavy drugs and earning money mainly through sex work, Tish couldn’t imagine herself aging as a female and transitioned back to Brian by the late ’80s. (“It’s easier to be an older man than woman.”)

This is undoubtedly a fascinating story, and luckily for the filmmaker, Brian is a chatterbox, full of enthusiasm and pride in his achievements. Now, after years of sobriety, he’s a married substance abuse counselor. (When Brian and husband Jim return to Providence, it’s a slice of Northeastern gothic.) In many ways, the film is a snapshot of the legal progress for the LGBTQ community during the last 50 years. It also takes an inadvertent look at male privilege, considering Brian had options that others who are transgender may not.

Documentaries focusing on 1970s New York City often wax nostalgic—Studio 54, to name one. Not so in this unexpurgated tribute, Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over by Beth B (a fellow artist from the ’70s downtown scene). The No Wave singer and spoken word artist—and self-described “successful predator”—Lunch holds court for the camera. She ran away at 16 from her Rochester, New York, family, where she had been sexually abused, and arrived in Manhattan in 1976 and immediately became the front person for Teenage Jesus and the Jerks. She was angry then and she’s even more outraged now—she calls her music dystopian and an “indictment against authority”—and today it seems as though the times may have caught up with her. She still tours with her band Retrovirus, celebrating a 40-year career and performing for an audience half her age. At 75 minutes, the movie is short and sharp. Lunch continues to look back, and forward, in anger.

American director Laura Naylor goes out into the vineyards of the family-owned Jacques Seloss winery in the sharp-eyed and affable Vas-y Coupe! (“Go Ahead, Cut”) and focuses mainly on a labor force that usually remains invisible to consumers (and filmgoers): the field workers picking the grapes. Every fall, about two dozen men from northern France travel to the Champagne region to eat, sleep, and work together for an intense two weeks. Some of the men have been returning for more than 30 years.

Shot vérité style, the hard-knock lives of many of these workers are implied; they arrive with plenty of booze—they can drink on the job, as long as they return the empty bottles. The atmosphere in the barracks comes across as more familial than boss/employer as everyone gathers for the evening meal. And yes, this film might confirm American viewers’ point of view of the French way of life; it devotes a lot of attention to the meal preparation of the women who work in the kitchen, besides offering an eyeful of the bucolic scenery.

Directors Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe witnessed the travails of Terry Gilliam’s ill-fated attempt to make a film based on Don Quixote in 2002’s wistful Lost in La Mancha. Floods washed away a film set, and other mishaps shut down the production. Some 16 years later, the filmmakers team up once more for He Dreams of Giants as Gilliam finally receives the green light to make his 30-year gestating project, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote.

Luckily for Gilliam, the events here are anti-climactic in comparison. After all, his movie was completed and premiered at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. If that revelation sounds like a spoiler, it shouldn’t. It was briefly released, though for one night only in a special event screening in April.

He Dreams of Giants is like an extended making-of documentary: typical for international co-productions, there are money worries, and the production also falls behind schedule. Yet there is little interaction with the actors, except for star Jonathan Pryce, who’s willing to do his own stunts (co-star Adam Driver barely appears). For die-hard Gillian followers, though, the film looks behind the curtain on some of his working methods, and a summary of his career doubles as a tribute to the director.

Leave A Comment