Writer/director Scott Z. Burns takes a deep dive into the U.S. Senate’s investigation of the CIA’s use of detention and enhanced interrogation techniques in the war on terror.

Burns has said that he was inspired by the mid-1970s films of Alan J. Pakula (The Parallax View; All the President’s Men) and Sydney Lumet (Serpico), and the influence is abundantly apparent. His production shares the grainy, dour palette of the aforementioned movies, and inhabits a pedestrian, realistic world.

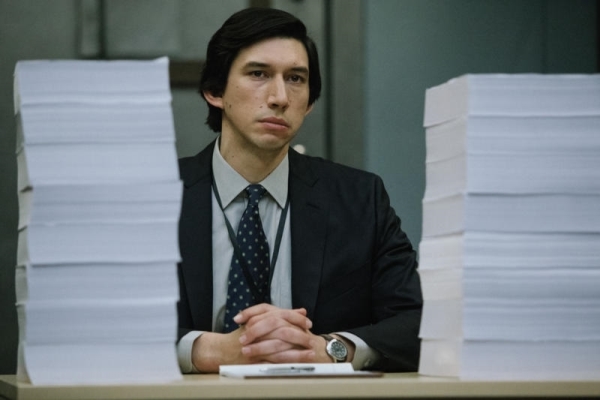

Much of the action takes place in a green-tinted basement, where congressional staffer Daniel J. Jones (Adam Driver) leads a tiny team compiling the report based on nearly 1.3 million pages of CIA records; the agency had destroyed tapes of the interrogations in question, leaving transcripts as the only record. No printer is available, and no one is allowed to leave the building with written material. A less glamorous depiction of Washington intrigue would be hard to find. Jones even encounters a valuable source in a garage, à la President’s Deep Throat.

With plenty of details about names and places thrown at viewers, the film demands close attention—and coffee. The story line takes a jagged trajectory from Jones connecting the dots during President Obama’s first term to flashbacks depicting graphic interrogations in the early 2000s, when the CIA deployed waterboarding and other harsh measures against terrorist suspects detained in unnamed countries, all in violation of the Geneva Convention.

The script is partially based on Katherine Ebanthat’s 2007 Vanity Fair article “Roschach and Awe,” which detailed the rivalry between the FBI and CIA and the former’s reliance on CIA psychologists James Mitchell (Douglas Hodge) and Bruce Jessen (T. Ryder Smith), who trained interrogators in unproven and sadistic interrogation practices. Their technique for breaking down detainees to confess and divulge information is code-named the triple Ds (debility, dependence, and dread), and the two come across as charlatans making up facts and figures.

The scenes of the report gathering have urgency largely because of the clipped editing. The reverberating and often overbearing musical score never lets the viewer forget that this is an info dump-as-thriller. Fortunately, Burns does not turn to the tropes of backstories or play up to the events of 9/11, the catalyst for the CIA’s actions.

The screenplay depicts Jones as the tenacious crusader and not a whistleblower; he draws within the lines, and he’s upfront with his boss, California Senator Dianne Feinstein (Annette Bening, distractingly coiffed to look like the politico), chairwoman of the U.S. Select Committee on Intelligence. As Jones, Driver’s performance begins at a low simmer as his character gathers facts, and his voice rises to near boiling as the report is stymied when the CIA tries to curtail the nearly 7,000-page document. Here, the actor is directed to feel the indignation that really should be more felt by viewers; he does a lot of the work for us.

By including a commercial advertising Zero Dark Thirty, Kathryn Bigelow’s portrayal of the hunt for Al Qaeda, The Report highlights how Burns takes a firmer, far more critical position against the use of torture than Bigelow’s movie. However, he ends his film with C-SPAN footage of Senator John McCain on the floor of the Senate condemning the use of enhanced interrogations. Bipartisan and powerful, this epilogue noticeably upstages Burns dutifully made assignment.

Leave A Comment