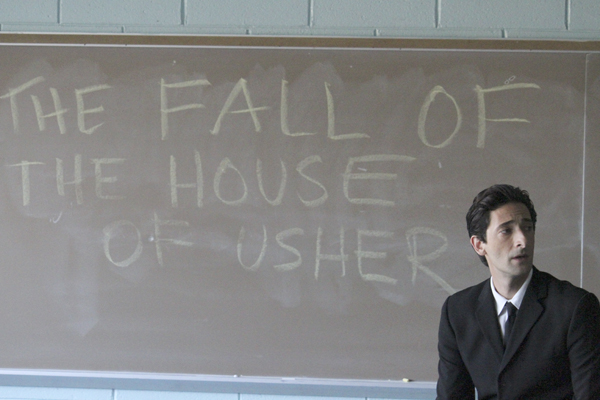

Adrien Brody in DETACHMENT (Tony Kaye/Tribeca Film)

Tony Kaye isn’t a stranger to making The Big Topical Movie. My introduction to him was as a teenager to the ferociously volatile but perfectly melodramatic American History X (about racism), and then just a few years ago with the surprisingly balanced and heartbreaking documentary Lake of Fire (abortion). And now we get his Big Education movie. For anyone paying attention to American life in general (or have seen other movies, like Waiting for Superman), it’s clear the school system can be messed up. At least, that’s the impression one gets from Detachment, where one public high school represents all that’s wrong with the system.

Adrien Brody plays Henry Barthes, a substitute teacher who goes from school to school, teaching for about a month in each, so it’s a pretty convenient position for someone who doesn’t want any ties to any one place. In theory, he comes in, does his job, and leaves. But in reality, he carries a lot of emotional baggage. His only real bond is with his dementia-ridden grandfather at a nursing home. Then over the course of a month, two things happen. First, he has a run-in with a runaway teen and prostitute, Erica (Sami Gayle), and he takes her in to his home temporarily. Second, he notices how despondent, tortured, and just pissed-off the teachers are at this school, and how disaffected/mean the students are.

For the latter, this isn’t through some inspirational Teacher-Comes-to-Save-the-Day tale. Henry is too lost to really be that super strong for the students. First, his tact is to try to not act superior to his students, but to treat them on a respectful but firm level. About a third of the way through, he says something like “You are victims of a ‘marketing holocaust!’” to describe this generation that he feels has been screwed over, and it’s the kind of heartfelt, cut-the-BS speech that any number of actors could given, but Brody finds a tone of sincerity, depth, and pain.

The title could already lend itself to some portentous view of the school system, but it also refers to Henry and his demons from his past, revealed through shaky 8mm film stock (the kind I probably have seen more than once, like in Gus Van Sant’s early movies). But what drives the film—and what also makes it a flawed work—is that Kaye’s direction makes this movie so combustible. It feels like it could come apart at the seams at any moment, or make the projector explode.

This is a director who doesn’t play by the rules, even as he intends to get the audience totally invested into the characters’ melodramas—Henry’s, that of the perpetually lost girl of the streets, and the teachers’. Suddenly we’re reminded again how good James Caan and Marcia Gay Harden are, and the build-up of Erica’s friendship with Henry is one of the film’s stronger parts. Young actress Sami Gayle rises to the occasion. But the real revelations are Lucy Liu, who delivers a brilliant meltdown in front of a student, and especially Betty Kaye (the director’s daughter) as the outcast student Meredith, who has a natural talent for art and photography and may be the most troubled of all in the cast.

By “not playing by the rules,” I mean Kaye wants to have two movies at the same time, yet they seem like the same movie as you’re watching it. While we have the story of Henry as the outsider and the reluctant protector of Erica, there’s also Henry talking directly to the camera at the start of the movie over the credits and in animated segues in between scenes—hell, in between certain cuts in a scene.

The effect all is jarring and strange, but I left the film shaken by how Kaye would grab me by the throat and not let me go till I had some kind of reaction to the drama, which is made realistic by the writing (Carl Lund is a former teacher) and by Brody’s performance. There have been times during his career when one has forgotten Brody won an Oscar for a Roman Polanski movie. There’s not a moment where he’s not compulsively watchable here. He plays a guy coiled up in his emotions, so when he finally lashes out—watch out.

Leave A Comment