FILM-FORWARD.COMReviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

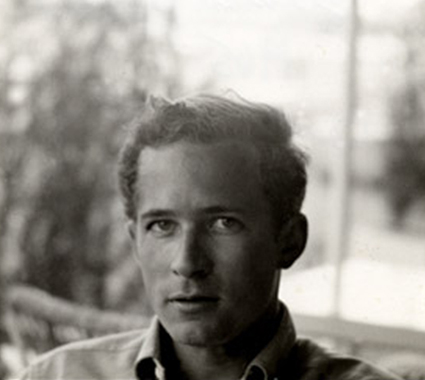

Directed by Esther B. Robinson Produced by Robinson, Doug Block & Tamra Raven Written by Robinson & Shannon Kennedy Director of Photography, Adam Cohen Edited by Kennedy Music by T. Griffin Released by Arthouse Films/Red Envelope Entertainment USA. 78 min. Not Rated For her first film, A Walk Into the Sea’s director, Esther B. Robinson, resuscitates the memory of her uncle, Danny Williams, one-time Warhol favorite and a filmmaker in his own right. In the summer of ’66, Williams, then in his mid-twenties, disappeared. His car was found near a cove, presumably where he went for a swim. His family found his stash of drugs, but no note, and his body was never found. Robinson’s film has a heartfelt urgency. It gets inside the competitive enclave of Warhol’s Factory, described as “cultish” by photographer Nat Finkelstein. However she did it, Robinson captures on-camera many of Warhol’s minions, even the flustered keeper of the flame, Paul Morrissey. In her interview, debauched former debutant Brigid Berlin doesn’t know if Williams and Warhol were lovers until she picks up the phone and places a call. The answer, yes. Warhol’s boyfriend at the time, Billy Name, wasn’t jealous of the liaison. According to him, Williams, a ’61 Harvard graduate, stood apart from the other “airhead” male hangers-on. Robinson’s uncle engineered the intricate lighting design for the Velvet Underground’s multimedia concerts and was allowed the honor of using Warhol’s camera to make short films, beautifully shot in black-and-white. (It was through an overheard conversation that led Robinson to the film’s treasure trove, the 16mm films Williams made while part of the Warhol’s entourage.) Yes, Edie Sedgwick does make an appearance in “Harold Stevenson,” which also features the painter dressed like a dandy embracing another man in evening wear. And even Billy Name makes an appearance. Not exactly documentaries, Williams’s films were more splinters of life, with an unmistakable gay overtone, like a lot of the films out of the Factory. And before he met Warhol, a 22-year-old Williams worked as an editor for none other than documentary filmmaker Albert Maysles, who remembers Williams with admiration.

The result of the interviews is the most vivid, and perhaps most damning, portrait of Warhol seen on film, exact but leaving a lot more to the imagination than

I Shot Andy Warhol and without the clunky exposition and half-hearted acting of the self-important Sedgwick biopic Factory Girl.

In Robinson’s film, Morrissey disingenuously claims that Warhol would not have approved of drugs, even though everyone, it seems, was on something.

John Cale, of the Velvet Underground, was high on meth. Berlin was encouraged by Warhol to “be outrageous” on the set. In his

film The Chelsea Girls, she stabs a syringe into her ass on camera. Berlin pretty much sums her own nadir which she also garrulously detailed

in her own bio-doc, Pie in the Sky: The Brigid Berlin Story. And even Williams’s mom knew about her

son’s use of amphetamines, yet she felt he was still “functioning.” (Robinson touches upon her own family’s history sporadically.) What mainly sets

this documentary apart from these other peeks into the Warhol era is that, unlike Sedgwick (model/photogenic arm candy/tragic icon), it’s clear what

Williams actually did and what he might have been capable of further accomplishing.

Kent Turner

|