|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

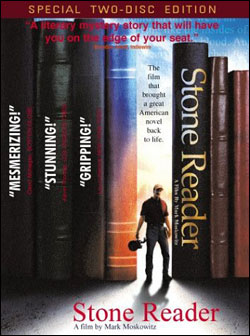

STONE READER

DVD Special Features

Stone Reader is a rather subjective and extremely personal depiction of the search for

how and why reading holds such great significance for, and influence on, so many people. Mark

Moskowitz, having been convinced as a college student in 1972 by a rave New York

Times book review to read Dow Mossman’s novel, The Stones of Summer, was not able to

get through it then. He did not get back to it again until 25 years later, at which time he thought

it was a phenomenal work. Looking for other books by Mossman, Moskowitz was mystified to

discover that the author never had anything published again, and had virtually disappeared off the

face of the earth. The film goes on to document Moskowitz’s adventures as he attempts to solve

the mystery of Mossman’s fate, and to ultimately track him down. Moskowitz finds himself in

discussions with such literary giants as critic Leslie Fiedler and Catch-22 editor Robert

Gottlieb. Fiedler suggests that

authors have to fall in love with writing, and with discovering themselves, in order to do what

they do – to which one could add that some part of the reader must do so as well. Perhaps,

though, author Frank Conroy sums it up best when he intones, regarding reading: “You feel the

pressure of another human soul on the other side of the book. And that makes you feel less alone,

and less trapped in your body. And less isolated…It’s almost spiritual.” Indeed it is. And as the

camera pans across shelves of books, viewers might start looking out for their favorites, such as a

stray Aldous Huxley or Kurt Vonnegut, and in this way feel that the film has captured readers’

ability to recognize some of themselves in another person who has read the same books.

Fittingly, that is the film’s most salient trait: the manner in which it communicates the

near-communal quality of reading, with storytelling emerging - since the age of hieroglyphics, as

its title also alludes to - as one of the most resonant human needs. Through it all, Moskowitz’s

sly sense of humor comes through. The film’s vistas of the Maine and Iowa landscapes stand out,

along with the evocative music. However, one feels the movie’s structure is flawed: at one point,

it becomes clear that Moskowitz is postponing a crucial development for maximum suspenseful

impact, a move that is too obviously contrived. Some scenes featuring Moskowitz’s children try

too hard to make the connection between books and their effects during childhood more explicit

– a link that has by then been established. Finally, the viewer might feel as if there should

be more about the novel itself - a Midwestern coming-of-age epic - since the movie ends up

being more about Moskowitz than Mossman or his book. Regardless, what happened to Mossman is a riveting story in itself.

DVD Extras: Most interesting for literary aficionados is a 1974 episode of Firing

Line in which William F. Buckley and interviewee Fiedler seem to be attempting to

outdo each other’s pretentiousness, with Fiedler hilariously making hand gestures that at one

point result in a seemingly oblivious giving of the finger to one of his questioners. Book fans will

also enjoy the Henry Roth segment, which compares the experiences of the similarly forgotten

author of Call It Sleep with Mossman’s. The interview with Betty Kelly, one of the

original editors of Mossman’s novel, emphasizes how much people were rooting for him to write

another book. A funny anecdote is found on the “What Happened Next” featurette in which

another fan of the book relates his frantic mission to bid for it online. The list of book

recommendations and the literary web resources will also be appreciated by the book

connoisseur. The piece de resistance, however, is an Easter egg found among the extras, a

short skit in which William Faulkner is asked permission by (what appears to be) a bad actor playing a

reporter to write a story on Faulkner’s everyday life. One minor gripe: the

segment in which Moskowitz talks to Janet Maslin, claiming that everything in the film occurred

as it happened, does not ring true, given the way the movie plays out and some obvious facts to

the contrary that Moskowitz states right after his initial proclamation, something which Maslin

lets him get away with too easily. A short film, “First Story,” directed by Cindy Stillwell, is

puzzling, since it consists entirely of footage of rodeos and trains, and is shown without any

explanation. As for the audio commentary, it is a treat to hear Mossman and Moskowitz get

along so well. One gets the feeling that Mossman is as genuinely grateful as he says he is, and it

is, admittedly, a kick to hear a writer appreciate other writers so blatantly. Furthermore, it is fun

to hear Mossman, in his folksy way, marvel at why paperback bindings are so easily broken in

the industrial power that is the United States, as well as slightly criticize Moskowitz’s film, at

one point calling his technique “schizoid.” Reymond Levy

|