|

Reviews of Recent Independent, Foreign, & Documentary Films in Theaters and DVD/Home Video

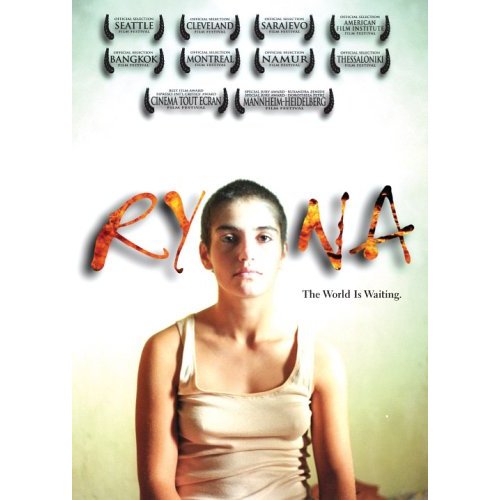

Directed by: Ruxandre Zenide. Produced by: Eric Garoyan. Written by: Marek Epstein. Director of Photography: Marius Panduru. Edited by: Jean-Paul Cardinaux & Ioachim Stroe. Released by: Lifesize Entertainment. Language: Romanian and French with English Subtitles. Country of Origin: Switzerland/Romania. 94 min. Not Rated. With: Doroteea Petre, Valentine Popescu, Matthieu Rozé, Nicolae Praida & Aura Calarasu. DVD Features: Trailer. Scene Selection.

The story of 16-year-old Ryna (Doroteea Petre in her film debut) unfolds slowly

in the hardscrabble post-Communist Danube Delta of Romania. Her tyrannical father (Valentin Popescu) projects onto her his wish for a

son by keeping her working hard as a mechanic in his repair shop, including helping him damage cars to spur his failing business, and

forcefully suppressing her burgeoning femininity and independence. He treats his family as ruthlessly as he does the cars.

She gets only fleeting support from her worn-out mother and her grandfather, who is wavering into senility.

In this small town “at the end of the world,” as one character describes it, everyone knows everyone’s business. Her father’s

insistence on Ryna wearing overalls and shorn hair could be seen as his way of protecting her from all the men buzzing around her, recalling such films as Osama and Baran where girls hide their gender for their family’s sake. Whether it’s the rambunctious peeping Toms, the flirtatious and jealous young postman, the corrupt and lecherous mayor, or the handsome French anthropologist (Matthieu Rozé) who comes to town for research, the men do all seem to have seduction on their minds. But those hanging around the local bar are even more afraid of the father’s drunken rages than his daughter is.

A couple of plot elements are quizzical. Ryna is said to have “weak blood” and the doctor says she has hemophilia, but that’s a males-only disease, so perhaps the subtitles should have said anemia. The anthropologist seems like a 19th century phrenologist, though instead of measuring heads he is measuring hands to ludicrously track the origins of the Latin civilization. And the comparison at one point to a situation as being like a “de Funès movie” is an ironic reference to the French slapstick comedian Louis de Funès.

Petre is nearly deadpan through much of the film, but her dark eyes flash attractively even in the most masculine garb.

A beautiful scene has Ryna shifting from the depths of depression when she thinks her mother has deserted her to joy at

getting good news. While the only privacy Ryna can find to cry is while repairing the undercarriage of a car, she finds rare freedom and relaxation photographing nature and stealing off to a local fair. These sweet respites are so hard sought that her father’s brutal treachery puts the audience into as much post-traumatic shock as Ryna and gives her self-possessed courage that much more resonance. As viewed on the DVD, the film is spare, with cinematography that is practically black and white and music that is only incidentally heard, including a sweetly mournful closing song over the credits.

Ryna joins the sparse ranks of recent films around the world by women directors who are giving audiences fresh and frank

portraits of the universal struggle of teenage girls to assert themselves and understand their sexuality and the effect they have

on men. In her debut feature, director Ruxandra Zenide, born in Bucharest and living in Switzerland since 1989, adds a sensitive

Eastern European perspective to the parallel insights of

Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen, Karen Moncrieff’s Blue Car, Lucrecia Martel’s The Holy Girl,

Catherine Breillat’s Fat Girl, Anne-Sophie Birot’s Girls Can’t Swim, and Cate Shortland’s Somersault.

Nora Lee Mandel

|